“Muir [was] concerned with imagination not only in order that there may be good poetry, but in order that man himself may survive.”

—Thomas Merton

The evolution of art isn’t as linear as modern art history makes it seem. Unlike science, which develops incrementally and—in theory at least—always improves on what came before, art often advances by revisiting (while, obviously, not mechanically repeating) previous styles and values. Such unprogressiveness implies a broader definition of contemporaneity than our own time generally allows. The postmodern aesthetic is insular in its judgment of what makes art relevant to contemporary life. Many seek no more from art than a mirror of what surrounds us in the present: cynical commercialism, built-in obsolescence, and virtual unreality.

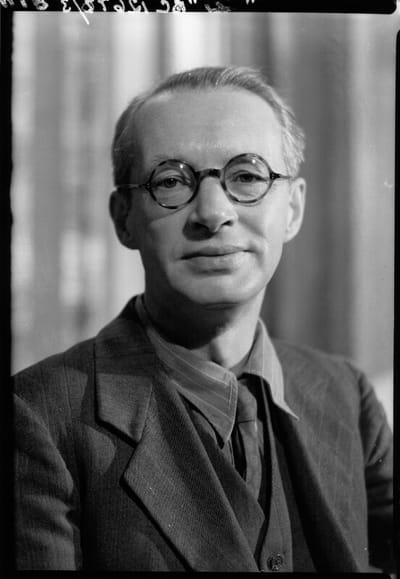

In such a climate it isn’t surprising that a poet like Edwin Muir has faded from view. Until the early 2000s or so, Graywolf Press kept his absorbing Autobiography in print; as well as The Estate of Poetry, Muir’s 1955–56 Charles Eliot Norton lectures on the relationship between poetry and society. These books were later taken up by independent print-on-demand ventures and can be found online. Muir’s Collected Poems was last published in 2003 by Faber, which also issued a Selected Poems in 2008. Not since the early 1960s, however, when writers such as Thomas Merton, Allen Tate, and Hayden Carruth were paying serious attention to Muir, has his poetry been discussed much in U.S. journals. One reason for the relative neglect of Muir’s poetry is its traditional, English and ballad-influenced prosody, which kept it obscure for many years even in Muir’s own time, when modernist poetics held sway; and its unironic high seriousness clearly doesn’t fit in with the cultural atmosphere of the early twenty-first century.

A singular quality of Muir’s writing is that it reminds us of the possibility of a rooted way of being and thinking. Muir was consistent in his distrust of the modern idea of progress; he warned that, in a culture overdetermined by technological development, outward changes happen so fast that our essential identity becomes “indistinct. . . . The imagination cannot pierce to it as easily as it once could.”

Muir’s style, however, isn’t the only or even the greatest difference between him and most of modern and postmodern poetry. Everyone who knows Muir’s work knows that he grew up as the son of a peasant farmer in the Orkneys, in one of the last communities in Europe practically untouched by Renaissance and Enlightenment culture—and that his poetry and prose are greatly affected, one might even say determined, by the struggle Muir underwent when circumstances landed him in the middle of several modern industrial and political nightmares. Like T. S. Eliot, Muir believed that contemporaneity includes a relation to the past, but the past to which Muir related his experience was not literary so much as ancestral and organic; “culture” for Muir meant everything from animal husbandry to Dante and Milton. He could afford to be less anxious about the relation of individual talent to tradition precisely because his tradition, while including elements of high culture, was more primary than the latter. It was based on the fundamental relationships between human beings living together in interdependent community with nature. Muir depicts his native community in his Autobiography:

I cannot say how much my idea of a good life was influenced by my early upbringing, but it seems to me that its sins were mere sins of the flesh, which are excusable, and not sins of the spirit. The farmers did not know ambition and the petty torments of ambition; they did not realize what competition was. . . . They helped one another with their work when help was required. . . . They had a culture made up of legend, folk-song, and the poetry and prose of the Bible; they had customs with which they sanctioned their instinctive feelings for the earth; their life was an order, and a good order.[[1]]

This background explains why, while most other modern writers were, in Ezra Pound’s words, writing from a fragmented stream, Muir was still vitally related to the lost world of social and cultural unity. When Muir wrote lines such as “But still from Eden springs the root / As clean as on the starting day,” he was expressing a sentiment many writers believed or felt but few could assert with real conviction. So it came about that Muir was one of those poets, rare in any age, whose vocation it was to bear witness to a vision of radical innocence and the fate of it in the world.

Muir’s equanimity is surely one of the things that attract his admirers. Though masterful, his writing is not technically flashy; nor does it reflect back to us our existential anxieties and fragmented identities. Rather, a singular quality of Muir’s writing is that it reminds us of the possibility of a rooted way of being and thinking. Muir was consistent in his distrust of the modern idea of progress; he warned that, in a culture overdetermined by technological development, outward changes happen so fast that our essential identity becomes “indistinct. . . . The imagination cannot pierce to it as easily as it once could.”[[2]] The constant metamorphosis of outer life brought about by technology obscures the essentials of human experience, which are remarkably consistent over time. In an essay called “The Poetic Imagination,” published in Essays on Literature and Society, Muir distinguished between technological and human progress:

Applied science shows us a world of consistent, mechanical progress. Machines give birth to ever new generations of machines, and the new machines are always better and more efficient than the old, and begin where the old left off. . . . But in the world of human beings all is different. . . . Every human being has to begin at the beginning, as his forebears did, with the same difficulties and pleasures, the same temptations, the same problem of good and evil, the same inclination to ask what life means.[[3]]

Despite the measured tone of this passage, which Muir wrote in his late fifties, his actual, early confrontation with industrialized society was personally calamitous. From his teenage years, when his family was economically forced to move to Glasgow (four of Muir’s family, including his parents, died within the next few years), into his mid-thirties, Muir earned a living at various menial jobs, experiencing preunionized labor and modern urban poverty firsthand. One clerical job, for example, forced him to live in a town entirely dominated by the company for which he worked, a factory that burned the bones of slaughtered animals to use the ashes for making glue. Muir describes the freight cars full of bones “festooned by the yellow cable of maggots,” and the rank stench of rotting flesh from which it was impossible to escape anywhere in town.[[4]] It is not surprising that Muir turned during this period to Nietzsche and socialism, the former, as he realized afterward, providing him with a rationalized fantasy of power in the face of overwhelming, impotent despair; and that the aphorisms he wrote at his desk at work were bitter and ironic, unlike anything he was to write later.

What is remarkable is that Muir did not become a social realist, like W. H. Auden, Cecil Day-Lewis, Stephen Spender, and other related British poets during the 1930s, who didn’t know anything close to what Muir knew directly about urban poverty. Instead, he applied his genius for symbolic or mythic thought to integrating his childhood and his adult experiences: “One foot in Eden still, I stand / And look across the other land,” as he says at the start of the title poem of his last collection, One Foot in Eden (1956).[[5]] Again and again, Muir’s poems address the archetypal dichotomy of innocence and innocence lost, often using Bible stories, especially Eden and the Fall, to communicate the sense of a chasm between living in unity with others and with God and nature, and living in isolation, dislocation, and dis-ease. Once he had regained the psychological vantage point of his childhood experience—after undergoing a breakdown in London, subsequent Jungian analysis, and finally leaving Britain with his wife, Willa (the first translator, along with Muir himself, of Kafka)—he referred to it in his writing as the ground or touchstone or prototype-of-wholeness against which he measured contemporary disturbance, flux, and change.

An interesting essay could be written about the animals in Muir’s poetry. Farmer’s son that he was, he does not depict animals in a Rousseauian wild state, but rather, in terms of humanity’s dependence on them. Muir’s most widely anthologized poem, “The Horses” (which Eliot referred to as a “great poem of the nuclear age”), treats this theme, and the related one of alienation and reconciliation between human beings and nature, with a masterfully paced narrative and vivid tangible detail. Importantly, Muir wrote this poem in the 1950s, the coldest period of the Cold War; it appears in One Foot in Eden. Muir sets up the poem in the first few lines with the contrast between unity and division that will structure the whole piece.

Barely a twelvemonth after

The seven days war that put the world to sleep,

Late in the evening the strange horses came.

. . .

By then we had made our covenant with silence,

But in the first few days it was so still

We listened to our breathing and were afraid.

And the poem adds that radios and remote communications had gone dead as well. The silence is uncomfortable at first; people don’t know what to do with themselves.

The first inkling of reconciliation with the animals is depicted later in this poem with confident simplicity: “Late in the summer the strange horses came.” The horses are “strange,” it turns out, simply because we estranged ourselves from them. The poem itself makes clear they are not wild, but are old farm horses. In a letter Muir wrote in July 1958 he states that he had wished to emphasize the relationship between the human and the natural world: the horses are “good plough-horses and still have a memory of the world before the war. I try to suggest they are looking for their old human companionship.”[[6]] Yet the speakers of the poem, a collective “we” (a common device in Muir’s poetry), respond to the horses’ return with fear of their instinctual energy, presumably because the machines with which they replaced them, the “dank sea-monsters” now “moldering away . . . like other loam,” did not require them to exercise their capacity for relating to living things. The speakers of the poem, then, don’t trust the horses’ return.

We did not dare go near them. Yet they waited,

Stubborn and shy, as if they had been sent

By an old command to find our whereabouts

And that long-lost archaic companionship.

With remarkable economy, this passage concretizes the idea of reconciliation; so Muir can conclude the poem with a specific image of renewal: “Our life is changed; their coming our beginning.”

This deep acceptance of our inextricable closeness to animals and nature, coupled with esteem for human culture and intellect, is one of the aspects of Muir that makes his work so clear-sighted and sound. Despite his mystical temperament, Muir always maintained a down-to-earth perspective. In his critical writings, he was as likely to appreciate Austen, Thackeray, and Rabelais, as Hölderlin; and he disliked the poet Paul Valéry for being too remote from everyday life. Muir’s equanimity and balance made it possible for him to appreciate a very wide range of styles and views; his 1926 volume of critical studies, Transition, is remarkable for its insightful and jargon-free characterizations of James Joyce, D. H. Lawrence, Virginia Wolff, and others. This tolerance for aesthetic and philosophical views markedly different from his own, along with his knack for illuminating generalization, are qualities that make Muir’s critical writings so rich and worthwhile. He never liked the so-called New Criticism, believing it reinforced (because it overintellectualized its subject) the already widening gap between writer and audience. Muir always remains familiar and approachable. At the same time, his poetry has features in common with the symbolist aesthetic that appeals to many metaphysical poets: expressive concentration, interpenetration of idea and image, and sparseness of quotidian detail. Muir’s distinctive voice is a blend of earthy directness and visionary idealism; his is a romanticism of the second half of life. As a deeply Christian man, he held to the doctrine of Incarnation as a link between the interior life and practical life; and rebuked John Knox, the Calvinist, for betraying that teaching by keeping the Renaissance, with all its worldly insights, out of Scotland.

For Muir, culture is the zone in which mind and nature, the timeless and the temporal meet and are reconciled. This is why he didn’t agree with Auden and other modernists who claimed that poetry is “useless.” Useless, yes, if by that we mean utilitarian; but incomparably useful when we remember that without art—without gratuitous beauty—a society can have no living dialogue with its own depths and heights. Muir believed that one of the tasks of art was to renew the ligatures that keep these connections current and vital, and that civilization itself cannot survive without such renewal.

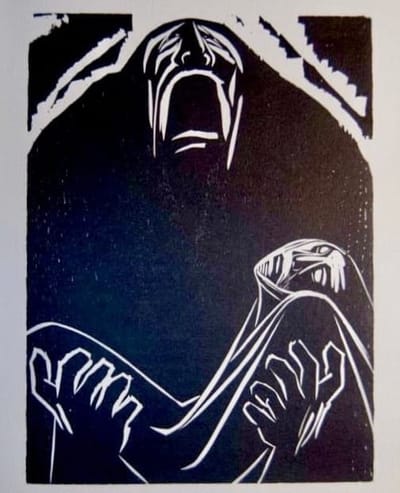

His own unique brand of political poem—and he wrote some fine ones during the Cold War years—was based on these notions. “The Usurpers” is one of several poems Muir wrote about his experience of postwar Prague, where he was director of the British Council Institute just after World War II, from 1945 to 1948. A Czech writer, a friend of the Muirs, had shown them a photograph of some young Gestapo men, one of whom had interrogated, tortured, and murdered her husband. She also showed her husband’s shirt, covered with dried blood and torn scraps of flesh, mailed to her by the Gestapo after her husband’s death. In his Autobiography Muir wrote of the men he saw in the photograph:

They all seemed to be in their late twenties, and it suddenly came into my mind that they had been bred by the first world war. . . . [Our friend] pointed at one young man and said without expression: that is the one who strangled my husband. But it might have been any of the others. They stared out from the photograph with the confidence of the worthless who find power left in their hands like a tip hastily dropped by a frightened world.[[7]]

Muir’s poem about the photograph is a first-person dramatization of the sort of mentality he ascribes to Regan, Goneril, and Edmund in his essay on King Lear (from a 1946 lecture), that mentality which sees “things in a continuous present divested of all associations, denuded of memory and the depth which memory gives to life, . . . claim[ing] a liberty which is proper to nature but not to society.”[[8]] “The Usurpers” depicts how casual the speakers are about dismissing traditional knowledge: “It was not hard to still the ancestral voices: / A careless thought, less than a thought could do it.”

This perspective, invaluable to the empirical methods of pure and applied science, which are based on systematic suppression of qualitative experience, devastates human life, which thrives on imagination, stories, and values that can be felt or intuited but not measured. The Gestapo men, like the power-obsessed characters in King Lear, boast of a

liberty

No one has known before, nor could have borne,

For it is rooted in this deepening silence

That is our work and has become our kingdom.

Dissociated from a culture that conveys a sense of meaning and relatedness, the speakers mistakenly believe that this alienation constitutes genuine liberty: “We dare do all we think, / Since there’s no one to check us, here or elsewhere.” And the end of the poem implies that the speakers’ naturalistic bias leads, ironically, to a cold objectification of nature: “It is a lie that they are witnesses, / That the mountains judge us, brooks tell tales about us. . . . // These are imaginations. We are free.”

The last line is especially telling: “freedom” in this sense requires the contemptuous or defensive dismissal by reason of all so-called superstitions of the past. Another of Muir’s poems from One Foot in Eden, “The Cloud,” satirizes political systems based on this attitude. It was written during Muir’s last year in Prague, shortly after the Soviet takeover. The communists—although their impersonality, said Muir, was not as cruel as that of the Nazis—were able to impose their system only by carefully censoring all spontaneity of personal relationship and feeling, a ploy Muir experienced firsthand when two government officials attended and took notes on his lectures at the university. For Muir, as he wrote in his Autobiography, the communists, like the Nazis, “called up a vast image of impersonal power, the fearful shape of our modern inhumanity”:

Their categories, the working class, the capitalists, the bourgeoisie, the communists, the anti-communists, were far more real to them than . . . human beings. Their moral judgments were judgments of their categories. . . . They could understand a good worker, but a good human being was an abstraction which fell outside their sphere of thought.[[9]]

One day Muir and his wife were driving to a writers’ retreat at Dobris Castle near Prague, when they rounded a corner and saw in a field “A young man harrowing, hidden in dust; he seemed / A prisoner walking in a moving cloud / Made by himself for his own purposes.” Muir, of course, knew nothing of this man’s actual political convictions. The lines are a satirical description of the worker that communist ideology supposedly defended. Muir is applying the anti-imaginative constructs of communism to one of its own, to show how it failed to provide the liberation of spirit it promised.

And there he grew and was as if exalted

To more than man, yet not, not glorified:

A pillar of dust moving in dust; no more.

. . .

We looked and wondered; the dry cloud moved on

With its interior image.

The Muirs continued on to the writers’ center, where they heard a talk by a “preacher from Urania,” who praised “the good dust, man’s ultimate salvation.” Communist ideology, Muir suggests, condemned the very person it claimed to free; it limited him to an identity entirely circumscribed by “the biological sequence,” so that he could imagine himself only as “a blindfold mask on a pillar of dust.”

Both “The Usurpers” and “The Cloud” are typical of the sort of political poetry Muir wrote: the subjects are universalized; the images and ideas, with few exceptions, could apply as easily to any place or time with similar circumstances. Muir almost always looked for the essentials behind and beneath surface conditions; his poems show us that politics, societies, and history are “fables” as well as literal “stories.” (The early version of Muir’s Autobiography was called The Story and the Fable because he wanted to tell not only his life’s events, but their context in the larger picture of things.) In Muir’s political poetry, history is reimagined as an internal event. Muir depicted our time as one of transition, an interregnum of civilization, during which the danger is great that we can forget altogether the meanings and associations that make specifically human life possible. His personal struggle to assimilate (for he never really adapted to it) this hyper-technological epoch resulted in some of the most singular writing of his time, immensely useful to those of us who, even if we have never known any other way of life, are trying to understand, articulate, and address the inadequacies of the modern world. Obviously, to move forward we can’t be merely sentimental or nostalgic about what we have lost or abandoned; but it is equally true that forgetting it limits us to our own myopic and dystopian creation. Muir’s poetry and prose are there to help us remember.

[[1]]: Edwin Muir, An Autobiography (1954; repr., London: Methuen, 1964), p. 65

[[2]]: Edwin Muir, “The Poetic Imagination,” in Essays on Literature and Society (1949; 2nd ed., Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1965), p. 225

[[3]]: Ibid

[[4]]: Muir, Autobiography, p. 143

[[5]]: All quotations from Muir’s poetry in this essay are taken from Collected Poems (London: Faber and Faber, 1984)

[[6]]: Letter to Derek Hawes, July 7, 1958, in Selected Letters of Edwin Muir, edited by P. H. Butter (London: Hogarth, 1974), p. 205

[[7]]: Muir, Autobiography, p. 267

[[8]]: Muir, The Politics of King Lear (New York: Haskell House, 1947), p. 17

[[9]]: Muir, Autobiography, p. 277