Translator's Introduction

Translated by Fatima Jane Casewit[[1]]

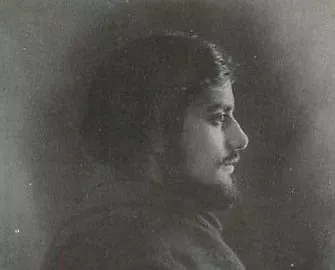

Impelled by a love of God and of mysticism from a young age, Aryah Lev Schaya, (Leo Schaya’s Hebrew name), tried to elicit God’s attention by tracing the forbidden Tetragram in the snow in front of a synagogue in Basil, Switzerland.

A few days later, he met Frithjof Schuon, who by then was a muqaddem[[2]] in Europe for the venerable Sheikh Ahmad Al-Alawi of Algeria. Schuon was giving a lecture in Basil about his recent encounter with the great Alawiyya Sheikh at his zawiya[[3]] in Mostaghanem (1932-33).

Leo Schaya listened in awe, later describing Schuon’s talk as “going from eternity to eternity.” He immediately made contact with Schuon, expressing his enthusiasm, and asked Schuon to be his spiritual guide. The two became close friends, as attested to by the frequent visits and their profound epistolary exchanges throughout Schaya’s life until his death in 1986. Later, Schuon would say that the only reason for the series of talks in Basil was his providential encounter with Leo Schaya.

Schaya was born in 1916 into a Polish-Jewish family who had immigrated to Switzerland when he was very young. His immediate family traced their heritage to many Hasidic rabbis, but the family was no longer practising their faith. Schaya was exposed in his youth to Jewish traditions, and he later extended his interests to other faith and wisdom traditions including neo-Platonism, Sufism and Advaita Vedanta. He initially pursued studies in commerce but later moved to Nancy, France, and devoted himself to the spiritual life and to writing.

He became known as a Perennialist author writing from the Jewish perspective. His most famous works are L’Homme et l’Absolu selon la Kabbale (Man and the Absolute According to the Kabbala, 1999) and La Doctrine Soufique de l’Unite (The Sufi Doctrine of Unity, 1981). He was editor-in-chief for Etudes Traditionnelles for several years and later founded another journal dedicated to the study of traditional sciences: Connaissance des Religions[[4]].

In 1950 Leo Schaya, by then known as Sidi Abdul-Quddus, travelled to the Muslim world for the first time, accompanied by a couple from Nancy who were his close friends. The three of them had been sent on a mission to Mostaghanem in Algeria with a letter from Schuon to the Sheikh ‘Adda Bentounes (1898-1952), one of the successors of the Sheikh Ahmad Al-Alawi. Their itinerary passed through Morocco. However, as Schaya relates in his journal, following his life-changing encounter with the Sheikh At-Tadili in Mazagan (Essaouira), Schaya abandoned his plan to travel to Algeria, and he returned to France with what he called “the living spirit of Sufism.”

He kept a diary during these Moroccan travels, which for him were life-changing and transformative, as described by several spiritual awakenings he was privileged to undergo, referred to in the diary. His journal of this trip, originally written in German, was brought to light only after his death.

This English translation is based on a French translation of Leo Schaya’s Diary presented by Professor Paul Fenton in the French journal Horizons Maghrébins – Le droit à la mémoire, no. 51, 2004.

The following are extracts from Leo Schaya’s Diary, divided into two separate parts:

Part One: From France to Fez and Moulay Idriss Zerhoun; and

Part Two: The encounter with the Sheikh At-Tadili. [Editor's Note: Part Two will be published in Volume 52 of Sacred Web, forthcoming.]

Leo Schaya's Diary: Journey to Morocco (Part One)

The Departure

26 October 1950

I bade farewell to the Master[[5]] and to Sayyida Latifa[[6]] to leave on a journey with Sidi Ahmed and his spouse. I was very sad because Sayyida Aziza[[7]] was not coming with us. This sadness surrounded me like the obscurity of a khalwa[[8]] and I could see almost nothing around us during our trip between Lausanne and Nîmes. All day I invoked and looked deep into myself. Later in the evening we arrived in Nîmes where Sidi Ahmed invited me to his mother’s home which was unoccupied at that time.

27 October

This morning I took a walk in the garden behind the house, a garden full of palm trees, pines, cypresses and olive trees. The surroundings recalled a Florentine landscape. Nîmes is full of memories of the Roman dominance: the arena, the temple of Diana, the Roman baths and the ancient sacred spring in the middle of the town… Everything whispers the old name of Nîmes: “Nemausus”. Yet, even before the Romans, Nîmes was a geographic centre; under the Celts it was called “Nemoz”, “the place of sacred gathering”, that is, the gathering around the blessed spring. I remained for a long time in front of the spring gushing forth from the centre of a pond which fed the Roman baths nearby.

It was noon. We left Nîmes for Perpignan. We passed fields of grapevines everywhere and continued to drive through cypress, pine, laurel, olive and palm trees. Above us a sky heavy with rain clouds opened up from time to time to a resplendent blue. Finally, the sun burst forth in all its strength and lit up all of the landscape like a cry of joy. And suddenly the sea appeared before us, no farther than several miles away.

We spent the night in Perpignan. Our objective for today’s stage of the journey was Barcelona. We had barely left Perpignan behind us when the blue Pyrenees mountains with their snow-covered peaks greeted us. And between us and the Pyrenees mountains stretched the olive-green hills with vast forests of beech trees. We were approaching the Spanish border. The landscape became abrupt and we had to pass over the peak of Junquera. The sun was burning; we were travelling into the direction of summer. The beech trees merged again with the pine trees, cypress and silver-lit olive trees. After crossing the border, we went through vast fields of grapevines once again. Then we saw the Pyrenees on the Spanish side, leaving them farther and farther behind us.

On the main road proud guard soldiers appeared. From time to time, we crossed a wagon pulled by a little donkey guided by a peasant whose eyes were fixed afar. Then we went through villages and small Spanish towns. Low houses with characteristic galleries were narrowly lined up one next to the other. We passed crowded markets full of small wagons and they were milling with people. All of it was bathed in the beauty of a wholesome folk-loving greatness; even the poverty here has a dignity and a particular purity, a poverty which in France, for example, is rather clothed in filth and ugliness. The landscape was also enveloped in another light than that of the south of France: everything is more clear, more luminous, more transparent, and more joyful; larger, straight-forward, with more clarity and pleasantly more harmonious.

We were no farther than 100 miles from Barcelona; the Spanish sea of a splendid blue suddenly displayed all its power and imperial spread and we drove along this immense water, passing through small white towns which were here and there sprinkled with Moorish homes…

The waves swept the shore, singing of ancient times: the Muslims who had debarked here, the exploration journeys toward the new world, the Spanish fleet which had founded the global power of the country, and the apogee of Christianity, the force of which still repeats itself in our day.

Barcelona greeted us from a distance – such an immense heap of houses that poured out over the sea; our car swiftly allowed us to approach them. We penetrated the noisy, mottled port town. Every possible vehicle crossed into one another’s path; frightened little donkeys wandered between heavy lorries full of mundane, opulent goods; proud soldiers, workers and Bohemians with women and children… everything buzzed with pell-mell.

We arrived in front of our little hotel, we ate, prayed and did some shopping which took us into the evening. We were able to attend a dance show. Never before have I seen anything so “Spanish”. The dancer was a unique fire… fuego, fuego, everything in her was infinite vibration and at the same time outwardly mastered. She sang, yelled, delirious, she stomped and returned like a queen who looked at her people – here, the spectators – very much below her stature. Around her a dancer singing with a stentorian voice making his declarations of love and finally, as proud as a toreador.

29 October

Today we went from Barcelona to Valencia. We followed the sea almost continuously, a sea of azure colours, of sapphire and emerald. We stopped in Tarragona for a snack. This small town is like an immense gallery which, at some several hundred metres of height, leans over the sea. After eating and enjoying the superb view of the sea, we continued our route. The sea accompanied us until Valencia and, when we penetrated the city in the evening, we had to make our way through colossal crowds pressing into the streets; a joyous atmosphere of festivities reigns here; Valencians live in the street.

30 October

I was awoken early in the morning by the Moorish calls of merchants in the street. The entire town seemed engulfed in a unique melody of flamenco. This ambiance full of music and bright colours did not leave us until the southernmost tip of Spain. The landscape between Valencia and Granada became more and more oriental: vast forests of palm trees flung out ripe dates, plantations of orange and olive trees spread over the whole surface of the hills; red pepper and little peanuts were ripening in the sun in front of houses; and everywhere friendly peasants emerged on their little donkeys or in their little wagons.

In Murcia, the town of Mohyiddin Ibn Arabi’s youth, there were many Bohemians, children crying, and women busy with manual work in front of their homes; a laborious poverty graced with golden cheerfulness. Night fell. We travelled on one of those desolate and rocky plains of Spain, above a resplendent moon surrounded by a legion of large stars which sparkled in the distance. In front of us a small fire threw up its lively light. We noticed dark silhouettes of Bohemians who were warming themselves. Suddenly Granada appeared below us enveloping the obscure calm of the night. Without seeing anything in particular of the town, we returned to our hotel.

31 October

Once again, the Moorish calls of the street vendors tore me from my sleep. The same calls went on continually for several hours. Who could resist them in the end? After lunch, we went up to the Alhambra: it is situated on a height and is surrounded by a pleasant cool forest. From here, we had a magnificent view of Granada, and from the other side, onto the vast plain in the direction of Andalusia. If we looked towards the East, the snow-covered Sierra Nevada sparkled in the distance.

Before entering into the Alhambra, a Bohemian came to meet us and read the palm of Sayyida Amina. Then we went through a door and before us opened up one of the greatest miracles of architecture in the world. The reproductions that we had seen of the Alhambra only very weakly expressed its beauty. It is not only the perfect harmony and beauty of the forms, but above all also the strength of the Spirit that penetrates the spectator everywhere. The Alhambra is a grandiose witness of the perfect unity of beauty and power, of spiritual and temporal authority. All the walls are sprinkled with the sentences: “There is no conqueror except Allah.” The Divine Name looks at everyone, everywhere; one finds oneself everywhere under the constraint of the supernatural. The ceilings of the rooms are cupolas almost from one end to the other; they are sculptured in the interior in a thousand ways: if one looked above one would think one were in the middle of a cave of stalactites. On the inside there is not one hand’s length of surface lacking sculpture; each stone seems to be shaped and spiritualized, piece by piece. And everywhere there is gurgling and murmuring; the water from a fountain of vast pools and delightful small streams express the joy of paradise as described in the Qur’an.

We left this fortification of Islam behind us and crossed high mountains in the direction of Málaga. A thousand metres below us, the sea. But between us and the sea, no less than eight mountain chains. Looking around whilst on the road, one is taken with dizziness. Everything is embalmed by mountain plants. Above here it was with joy that the Spanish bandits of yesteryear must have had their heyday, today they seem to have disappeared. In their place we saw kind peasants on their innocent little donkeys. One would think one were on the roof of the world. Our observation was lost in the scents of a distant infinity, where no horizon is bound by the surroundings. From this view, the soul lives such an expansion that one can hardly not let out cries of joy. We had to almost force ourselves to leave this place to descend towards Málaga.

We arrived at the sea and entered into the town. Once again the joyful tapestry of streets, the young trop of beggars who ran after our car to offer us some service and thus earn a peseta. We were sitting in front of a café when two street musicians arrived and sang for us the most beautiful flamenco. Then the road continued along the sea towards Algeciras. A blood-red sky above the sea shaded us. We were approaching Africa. Lighthouses threw out their light. Gibraltar sparkled from afar in the night. We finally arrived in Algeciras and settled again into the hotel. The next day we went to the port.

Dar al-Islam

1 November

Before us, we could see the African hills; a short arm of sea separated us from the other continent. A crane loaded our car onto the boat, and we were already navigating into the direction of Tangier. For three hours, we navigated along the Moroccan coast. Behind me was seated the Arab servant of a little bourgeois Frenchman. In this case, it was the servant who incarnated all the nobility, whereas their masters behaved like insolent slave people.

We crossed the narrow barzakh[[9]] which separates the West from the East, and the Mediterranean Sea from the ocean. The white and blue medina[[10]] of Tangier approached us more and more; the sun was setting into the sea and on the summit of a minaret a small light was shining announcing the evening prayer. We were still too far away, however, to perceive the call of the muezzin.[[11]] Finally we entered the port, teeming with Moroccan workers, hotel employees and porters. A tangle of djellabas[[12]] of all colours, shouting in Arabic, and barely had we alighted from the boat that we were assailed by ten indigenous people. One wanted to carry the bags, the other wanted to take us to our hotel, whereas the other wanted to drag us to a consulate. In the meantime, our car was being loaded off the boat and we made our way towards the town. I thanked God for having brought us safely to Dar al-Islam.

For the first time, I saw veiled women; similar to nuns enveloped in white clothes, they circulated in the streets – a beautiful sight in the darkening city. The mysterious Orient begins here, which for us has almost no more secrets.

When we arrived at the hotel, we established contact with Sidi Abd At-Tawwab, who was very surprised and joyful at our arrival. We took the evening meal together and then went to his home where I met his wife, who received us with much kindness. We spoke very late about the events of the past months.

Tangier

2 November

This morning Sidi Abd At-Tawwab showed me around the town, the old Jewish cemetery and the Arab market. Then he took me with my companions up to the heights of Tangier where one is treated to an extraordinarily beautiful view of the sea and the town. Like a smiling blue marvel, the ocean stretched out below us. Then Sidi Abd At-Tawwab pointed out in the immediate proximity one of the houses belonging to his Arab friend Hadj Ahmed, a very wealthy and pious man who had already made the pilgrimage to Mecca five times and who would consider himself extremely happy if the Sheikh[[13]] came to stay in this beautiful house. A large garden with flowers and deliciously smelling plants surrounded the house, not far off was a small mosque; to go down to Tangier was a half-hour trip. Then we arrived at the home of Sidi Abd At-Tawwab.

We made up our prayers, then we were called for the meal. Still other guests joined us – noble personages. It was only later that I learnt that they were the greatest Ulemas[[14]] of Tetouan. The most important amongst them was Sidi Baqali. During the meal I spoke of the Sheikh and of my journey. After the meal, Sidi Baqali pointed out an ayat[[15]]that I should recite before each prayer. Hajj Abd As-Salam mentioned another ayat that I was to recite before each journey. It was the ayat that Sidi Ali fell upon when, before our departure from Lausanne, he had opened the Qur’an in posing the question as to whether we should undergo the journey. Then I was asked if I knew how to read the Qur’an. I recited the surahs[[16]] Ya Sin, Al-Waqi’a and Ar-Rahman. The assembly seemed very satisfied. Then I explained the spiritual meaning of Ayat An-Nur. Hadj Abd As-Salam told me that my interpretation completely corresponded to the Sufi writings and he added: “Only he who himself is full of divine light can also speak about divine light.” Then the visitors bade farewell to one another whereas we – Sidi Abd At-Tawwab and me – reclined as guests, on the quite low Moresque beds, so as to sleep… but sleep, in this case, was rather the intention of an act; we were in fact kept awake almost all night by conversations in Arabic which were going on, on the floor below. When we had finally dosed a little, towards the morning we were torn out of sleep by vigorous knocks on the entrance door and a blast of canon.It occurred to us that it was Friday, and this meant that we should hurry as quickly as possible to the morning prayer… And I was already hearing the muezzin make the call. Quickly we made our ablutions. We left the house with Sidi Hadj Ahmed; it was still night and the moon shone like silver in the sky. In the mosque, nobody was there yet except the Imam[[17]] who was seated against a column, and who stood up upon our arrival. He was a young man, very handsome and distinguished with a noble face, almost tender, and with a black beard. We prayed with him; his prayer was simple, full of dignity, filled with a strange peace and profound humility. Hadj Ahmed told us later: “He prays like a saint.”

Then we returned home where Sidi Abd At-Tawwab and I recited the rosary. Even though Hadj Ahmed was not a faqir[[18]], he sat next to us and recited the rosary with us. After this, he gave me a Qur’anic manuscript with Qur’anic calligraphy, almost illegible for me, so that I could barely read passages. I told him I was not used to that writing. He responded: “We can read together.” I began to read, he sat right next to me and every time I was blocked, he helped me to carry on and this with the greatest simplicity and humility.

Chaouen

3 November

After lunch we left for Xauen (pronounced Chaouen), which is on the road to Fez. Chaouen is a charming mountain location with the purest Arab life. The home of Hadj Abd As-Salam is located here. While the latter got into our car – where unfortunately there was no place for others – Hadj Ahmed took the bus to get to Chaouen. There we all met in the Abd As-Salam house. Then we ate again and spoke about Islam. On the wall hung a large portrait of the late father of Hadj Abd As-Salam who was a Darqawi faqir. He had invoked the Divine Name night and day, almost continually. Hadj Abd As-Salam said that when he woke up in the night, a light-breath “Allah” came to the ear. The portrait of this man left a great impression on me: his great spiritual rigour and the firm resolution to give his life for God! When Chaouen was being bombed during the Rif war and the population was hiding in cellars, he went to offer help in the street. When the others warned him about risking his life, he merely answered: “I fear nothing because the day of my death is written and nothing can change that.” Then I had the honour of greeting the mother of Hadj Abd As-Salam aged 90 years; I was told that she lives like a saint.

Then we went to walk in the mountains of Chaouen; it is a region at once vast and full of crevasses and covered with luxurious vegetation, full of olive trees, cypress, pines and a variety of lush trees. At one end, in a place where a part of the mountain juts out, is a deliciously cool spring which waters the entire area. This beautiful region, unique of its kind, has been called the “Granada of Morocco” given that the Arabs who were expulsed from Granada settled here. But the landscape also reminds one in many respects of Granada: a white conglomeration of houses outlined on the mountain in a strategic position with views of the vast countryside.

During our walk on the edge of the mountain, we finally arrived at the tomb of the saint Sidi Mohammed Al-Wafi. He was a black sherif[[19]]who almost a hundred years ago suddenly appeared on this hill in front of the town without any inhabitant of Chaouen having seen him before; he sat there and invoked God’s Name night and day until his death. We prayed the afternoon prayer in front of his tomb. Then I entered the sepulchre, kissed the stone under which the saint lay and prayed for a moment.

Then we had matting brought by a retired French-Moroccan soldier and spread them out on the side of the mountain. We sat there and lost ourselves for a long while in the vast countryside situated far below us. From the Chaouen market square, came the trace of a sound of a tambour whose measure of beats indicated the frenzied dance of dervishes…

We went back into town where we were first taken to the home of Hadj Abd As-Salam’s brother-in-law to make the evening prayers. It was a marvellous Arab house with a large artistic fountain in the inner courtyard. The ground as well as the walls were covered with slabs of varnished stones. After the prayers we returned to Hadj Abd As-Salam’s place where we took supper and told each other Sufi stories. Although we had been invited to stay with him, we stayed at the hotel because we had to regain our strength after the insomnia of the night before.

Fez

4 November

Before our departure the next day, 4 November, we were introduced to the Muqaddem[[20]] in the shop of the brother of Hadj Abd As-Salam, Sidi Rahmaniyah, representing the Alaouites[[21]] of Chaouen. He was a young man, extraordinarily handsome, full of purity and love. I was reminded of Joseph of the Bible: a noble dark brown face, slightly elongated and surrounded by a black beard, dark shiny eyes, a long well-shaped nose as well as beautiful large lips, a deep forehead and a white turban wound around several times. He was of tall stature and dressed in long white clothing, in his hand a shepherd’s staff. This figure plunged us back into the era of the Old Testament. He had waited for me some time in the shop, I had been told, continually murmuring the Divine Name. When I entered, he rose, moved with joy, and hugged me interminably. We exchanged cordial greetings. He said: “If Chaouen had known who was here, everyone would have come running!” I told him that unfortunately, because of the Spanish authorities, I did not dare mix with the dervishes and that I now had to return to Fez. We spoke again for a moment of Sheikh ‘Aissa[[22]] and of Sheikh ‘Adda.[[23]] Sidi Rahmaniyah told me that one day, before becoming a dervish, he had sought out Sheikh ‘Adda because he could barely use one foot. The Sheikh ‘Adda put on Sidi Rahmaniyah’s babouches[[24]] and walked around in them all day. In the evening the Sheikh ‘Adda returned the babouches to Sidi Rahmaniyah and the former placed his hand on the injured leg. Sidi Rahmaniyah arose and began to walk again. This miraculous cure had convinced him to become a disciple of Sheikh ‘Adda, of whom he spoke with enthusiasm.

And suddenly the immense city spread before us, like a strange image from the tales of One Thousand and One Nights. It was sunset and 70 muezzins made the call to prayer. From almost everywhere, proud minarets surged up from the labyrinth of houses. The medieval city ramparts wrapped around the town and in the surrounding area, there were only hills with trees and bushes. Fez lies in the middle of these hills like a heart in a vast basin bowl. Involuntarily, I gave the name of this splendid place the “Town of Allah.”

He again said: “Before becoming a dervish I had been feeling very bad. Since my entrance into the Order, I feel well, as do my loved ones; praise and thanks be to Allah!” Upon bidding farewell I could barely extract myself from Sidi Rahmaniyah’s embrace. Then we went back down the mountain. Sidi Abd At-Tawwab accompanied us by car until El-Kasr al-Kebir (Guadalquivir), where we had to cross the French-Spanish border. It was here that Sidi Abd At-Tawwab bade us adieu and it was sad to have to leave him, this devoted, caring and spiritual friend.

From the French-Spanish border we went straight to Fez, through a desolate and rough Morocco. We had the same view on the horizon that opened onto all the directions of space. Behind the faraway hills which emerged in the setting sun, the mysterious and legendary Morocco whispered. Here and there we passed some Berbers balancing on their little donkeys, and from time to time a few camels passed us. Not far from Fez, on one of the lowest hills located along the main road, a solitary dervish recited his rosary. Then from a little village located below us came the sounds of drums and playful flutes. On the market square, some musicians and children danced… we knew that we were now truly very close to Fez…

And suddenly the immense city spread before us, like a strange image from the tales of One Thousand and One Nights. It was sunset and 70 muezzins made the call to prayer. From almost everywhere, proud minarets surged up from the labyrinth of houses. The medieval city ramparts wrapped around the town and in the surrounding area, there were only hills with trees and bushes. Fez lies in the middle of these hills like a heart in a vast basin bowl. Involuntarily, I gave the name of this splendid place the “Town of Allah.”[[25]]

After this first encounter with Fez we went to our hotel. It was the old Arab palace of the noble family of the Jamai’i. A luxurious garden full of energizing perfumes spread behind this hotel. I was taken to my room, the floor of which was covered with beautiful Moroccan rugs. I felt at home here, for the first time since my departure from Lausanne, I felt a great benediction which filled me with light. I invoked God for a long time and I was at the centre of the world. That night, the Sheikh appeared to me in a dream; he kept me a long time. Great love poured from him; he filled me and made me indescribably happy. I could not have had a better welcome as a preparation for Fez.

5 November

Today we went through the medina with a guide; this is the only way to make one’s way through the indescribable labyrinth of the narrow and tortuous streets of Fez. As in the old city of Chaouen, one also felt suddenly transported several hundred years back; we were plunged into the medieval times of the East. Each neighbourhood of the town is reserved for a brotherhood. Here were the drapers, there the jewellers, the wall of a small fruit shop leaning against others and down there from souk to souk were only babouche displays. Then having crossed the laborious hammering of the iron workers one arrives at a long row of notaries and lawyers, seated in their shelters and dealing with their clientele come in search of advice. All the medina hummed like a great hive, every strata of the population paraded before us; every human expression struck us, from the blind beggar, miserable and toothless, sitting in a dark corner addressing his supplication with a broken voice all day long both to humanity and to the divinity, to the proud caid[[26]], who, with perfect nobility roamed through the small streets on his lavishly-harnessed white horse. Apart from a few Berbers, all the women were veiled. During our walk through the streets the refined and sometimes effeminate features of the Fezzis alternated with the vigorous and powerful expressions of the Kabyles of the Rif. Whereas the Fezzi almost never wears the red Turkish “fez” hat anymore, the Berbers remain faithful to the turban. At the far end of the street a water carrier passing in front of us announced himself with a small bell. His goat-skin tank filled on his back, he belongs to the poorest of all the brotherhoods and is distinguished, from other Fezzis wearing long djellabas, by his short garment. Most of the time the water-carriers wear a pointed leather cap as a head covering. The narrow “tail” of the cap trails down onto the back so well that one could imagine these water carriers, in their outward appearance, as characters out of the western Middle Ages.

We would only take three steps through the souk when the cry balak!(careful!) would catch our ears and this meant that we had to quickly fasten ourselves against a wall to let the heavily-laden mule pass by.

The confusion of the crowd increased with the large groups of children in Fez; where there was any space left in the labyrinth of small streets, they played and jumped, shouting, and thus contributed to the joyful and colourful life of the medieval town. Wherever there were gaps in the souks, mosques with their doors or windows open, allowed a glimpse into their sacred life. At the time of prayer, one could see hundreds of believers bowing and prostrating before the one God. Our attention was drawn mostly to the great mosque of Moulay Idriss II[[27]], as well as by the Qarawiyyin[[28]] mosque, which at the same time serves as a teaching space. One often also saw Fezzis pray in their souk or recite the Qur’an amongst the assemblage of their merchandise. Thus the outer and inner lives of people intermingled here, similar to the miraculous curves of an Arabesque design which continually give onto God… We then walked in front of Bab Guissa where we contemplated the house where the Sheikh and Sidi Ibrahim[[29]] had lived.

6 November

Today is 6 November. In the morning I left Bab Guissa alone heading up to where the cemetery is located.

From there, for a long while, I contemplated Fez which stretched out below me. Then I walked again in the medina and marvelled at its joyous activity. We were invited to take the midday meal at the home of the merchant Sidi Laraichi, a man very well disposed towards us, but very worldly and in admiration of all modern novelties. Whilst Sidi Ahmed and his wife spent the afternoon with him, I returned to our hotel where Sidi Abd Al-Karim Duval was waiting for me; he looked like a native. I spent the entire afternoon with him; we spoke of the Sheikh, of the Tariqa and of Tasawwuf. We were invited for the evening meal at the home of Sidi Haddu Delorm, in the Funduk[[30]] where one could see, next to small sick donkeys, gazelles which also needed care. A mountain of couscous again landed in front of us, and there was nothing left for us to do but to give ourselves up to the demanding hospitality of the Orientals. Sidi Haddu had also invited a poor Qarawiyyin student who ate heartily with us and then recited surah Ya Sin in the most beautiful way. Sidi Haddu had already been in Islam several years but until that time, had remained exclusively in the Shari’a (exoteric law). I had the impression that it was the best solution; as he did not seem particularly gifted for tasawwuf (Sufism). This lack did not however give the impression of self-denial.

7 November

We left for the Mellah, the Jewish quarter of Fez. Old Jews with little black hoods, black and white djellabahs; rarely of beautiful stature. Many dirty children and deformed women. We visited the cemetery and the 400-year-old synagogue. It was the cemetery that made the greatest impression, as contradictory as that may seem. Beautiful white and blue stones covered the tombs, which were closely aligned one against the others, like the houses of a peaceful and pure town; whereas the Mellah is dirty, noisy and chaotic, somewhat like the neighbourhood around the port of Marseille. The old synagogue[[31]] is star-lit with oil lamps, which serve as commemorative lights for the deceased members of the community. The walls, scattered with Moorish stucco works and with Hebrew inscriptions, were the most beautiful parts in the synagogue. For the rest of it, sad benches, a wobbly lectern; everything was full of dust and miserable without a perceptible spiritual presence… The only living things in this space were the birds that entered through a skylight and which fluttered on the ceiling. We spent the rest of the day in the souk, buying gifts for our friends.

8 November

The next day, 8 November, we left with Laraichi for Sidi Harazem which is located a few miles from Fez – a marvellous oasis with continually flowing thermal water and many palm trees, and populated only by natives. A few men and boys romped in the water and, in a rather hidden area women washed and bathed. In the middle of the village is the tomb of Sidi Harazem a great Sufi of the Middle Ages who had discovered this place. I entered the sepulchre to pray.

Here, in this oasis, one is in another world; a sweet and marvellous peace reigns here, and one wanted to sit in the shade of a palm tree to be absorbed immobile in the Divine.

Upon our return, we passed a marvellously beautiful young Jewess arm-in-arm with her mother. With her large dark eyes and shiny, long black hair she completely resembled a Spanish dancer. Then we returned to Fez.

In the evening Sidi Ahmed and I walked through the dark medina until we arrived at the souk. There we sat in the corner of a small shop where we ate bread with grilled meat, accompanied by green tea. At two in the morning I was pulled from my sleep by pleasant psalmodies. Two or three muezzins recited verses from the Qur’an for the sick or for lovers who couldn’t sleep; a beautiful and unique institution of the town of Fez…

At that moment the suffering of all humanity seemed to invade me, and my own sadness which had engulfed me during throughout this trip in Morocco came back to my conscience. Although sometimes, landscapes of irresistible beauty or marvellous people captivated my look for an instant, I nonetheless remained sad, and I simply wanted to end my trip and return home. What my heart sought was spiritual Light, and not people, houses, trees, mountains, not one form or another. Is the Divine Name not the most perfect and most universal form? For he who has contemplated this Name, all other forms will appear to him imperfect and even pure nothingness. Is the Divine Name not the luminous centre of the world? Am I not in this ever-present centre when, at home in my little corner, I invoke God? He who enters into the Reality of the Divine Name sees eternal, supra-spatial things that the physical eye cannot see. What we see on the exterior is a motely dream which disappears rapidly; and the more beautiful the world surrounding me is, the more transparent and purely symbolic it appears to me. Whatever is terrestrial carries death; only in the heart can one find the Supra-terrestrial, the Immortal, the Informal, the Archetype, That which has never been contemplated by any human eye…

Fez was torn before my inner eye like a veil woven of the ephemeral. Here in Fez precisely the place where I gloried in its visible sights, I had the experience that there is nothing to be seen, apart from the Divine Form…. and seventy muezzins cry out five times a day that there is nothing else to hear except the Divine Name: Allahu Akbar!

Moulay Idriss I

We left Sidi M. Faroul to go to Moulay Idriss I, one of the most important pilgrimage sites of Morocco. We arrived just before sunset: it is a superb mountain locality which rises towards the sky like a pyramid. A guide took us to the interior of the town, in front of the mosque tomb of Moulay Idriss I. There we bought candles and had some lit on the tomb of the saint, and took others with us as carriers of blessings, after having briefly lit some at the same site. As we were mistaken for unbelievers by the authorities, we unfortunately could not enter the sepulchre. While we were in front of the mosque, we heard a joyous sound of flutes and drums. A wedding parade had arrived in our direction; the gifts for the husband were brought by a small donkey, and, behind on a second donkey, was the completely closed chair of the bride who was secluded from the gaze of onlookers, and was on her way to the mosque to receive nuptial blessings. In all of Moulay Idriss I, there is not a single Western resident to be found because in this place of pilgrimage no non-Muslims can reside. We left that night and returned to Fez.

Fez

10 November

It was Friday. We had carefully prepared for our planned adventure. Already at midday we put on our Arab clothing in the car so as to be able to leave the hotel at 5 in the afternoon with empty hands; we had been told that the police were watching us. At five o’clock we went to the Funduk of Sidi Haddu. There we waited for Sidi Abd Al-Karim Duval and Sidi Mohammed Faroul. We were dressed like Arabs, all in white. We prayed the maghreb prayer, then, just like the caids, we drove in the darkness through the outer quarter of Fez in Faroul’s car until we arrived at a road where he stopped. We got out and walked in two’s, reciting holy invocations as the Arabs do, through the small streets of Fez, which for the most part are only slightly lit, in contrast to other streets which remain bathed in a crude light. The Arabs were looking at us; we walked straight ahead with small, measured steps as the locals do. A child shouted out to us: “Imposters!” but we paid no attention to him. After a quarter hour of worry, we finally arrived at the zaouia[[32]]of the tariqa Sqaliya where the sama’[[33]] had already begun. We sat in the circle and sang with the others. Gathered together were Sidi Hadj Al-Kabir Sqali, a robust beautiful elder with a reddish face and a beard white like snow; he was considered the Sheikh, although he refused this dignity through humility; next to him was Sidi Mohammed Chraibi, the old muqaddem who led the dhikr and of whom Sidi Ibrahim had already spoken to me. The rest were younger and older fuqara[[34]], one next to the other, none of whom particularly struck me.

The sama’ became more and more rapid. Finally, we stood up and danced. Some of the singers threw out an ecstatic, piercing cry into the Fez night. More and more fuqara appeared in the circle and reinforced the forceful breath of the panting dancers. Sometimes I thought I would faint, the dance became so rapid and wild; but suddenly my body was spiritually dissolved. I could no longer feel it, and my dance became as wild as that of the natives, corporeal limitations no longer existed for me and I could have continued to dance like that indefinitely. But the muqaddem gave a sign, and everyone sat down. The assembly prayed long verses of benediction upon us, their guests. Then we got up again to pray the night prayers, Sidi Al-Kebir officiating as Imam. The perfect humility of this man shone through his simple and majestic prayer. After the prayer I wanted to kiss his hand, but he pulled it away. He had lived in Mecca for twenty years, and twenty years in Medina. Finally, at the moussem,the pilgrimage celebration at Moulay Idriss, he sat on the tomb of the saint and, in the morning, when everyone who had been asleep around him got up, they saw him still sitting there, immobile.

In the zaouia after the prayer I heard them calling ‘ya Rabbi’.[[35]] They were all very friendly with us and, after the majlis,[[36]] Sidi Mufaddal Sqali, a Sherif and great grandson of Sheikh Sqali, the great founder of the Order, accompanied us, wearing Arab clothes, to the home of Sidi Haddu. We again went through the winding little streets of Fez and then we returned to the Funduk. There we ate couscous and drank a lot of green tea. I must have gone out into the cold night with my clothes wet from the dance; that was how I caught a good cold and swelling of the tonsils. I couldn’t fret about it, however, and had to behave like a good, cheerful guest. Sidi Sqali sang and recited one Sufi poem after the other and we sang with him as much as we could. One part of this poem particularly impressed me. It was one of the verses of Omar Ibn Al-Farid who says something like this:

…then a spark of my Being

Became my Totality,

My heart became the Sinai

And I became the Moses of my time!

Then we drove Sidi Sqali to Bab Guissa, where we bade him farewell. At the hotel I spoke with Sidi Ahmed late into the night about Tasawwuf.

[[1]]: Edited by M. Ali Lakhani. With much gratitude to Mr. Ishaaq Valodia for his careful editing and for the photos of Fez and Moulay Idriss I. And many thanks to Mr. Ismael Zerguit for bringing this diary to our attention.

[[2]]: A representative of a Sheikh, spiritual master.

[[3]]: Literally “corner” but referring to a gathering place of spiritual seekers.

[[4]]: Connaissance des Religions was founded in 1985 and operated till 2005. Its later editors included Jean Borella and Michel Bertrand. Its orientation was Guénonian.

[[5]]: Referring to Frithjof Schuon.

[[6]]: Frithjof Schuon’s wife.

[[7]]: Leo Schaya’s first wife.

[[8]]: A spiritual retreat.

[[9]]: A barzakh in Arabic is an isthmus or narrow passage. The word often refers to the passage from one world to another.

[[10]]: A medina means town in Arabic and refers to the original Arab towns in Morocco.

[[11]]: A muezzin refers to the caller of the five daily prayers from the mosque.

[[12]]: A djellabah is a long garment for men, commonly worn in Morocco.

[[13]]: The Sheikh refers to Frithjof Schuon.

[[14]]: Plural of ‘alim, a wise, knowledgeable scholar of the Islamic sciences.

[[15]]: A verse of the Qur’an.

[[16]]: Chapters of the Qur’an.

[[17]]: An imam leads the communal prayer.

[[18]]: A faqir – a poor one – before God.

[[19]]: One who can claim to have descended from the family of Prophet Muhammad.

[[20]]: A representative of a Sheikh in Sufism.

[[21]]: Also, Alawiyya, a tariqa founded by the Sheikh Ahmad Al-Alawi of Mostaghanem, Algeria.

[[22]]: Refers to Frithjof Schuon.

[[23]]: One of the Sheikh Al-Alawi’s closest disciples and later his Muqaddem.

[[24]]: Traditional Moroccan slippers.

[[25]]: Schaya’s descriptions of Fez are reminiscent of those of Titus Burckhardt in his book, Fez: City of Islam (1992, Islamic Texts Society, translated from the German by William Stoddart), which evoke the sacred milieu of this ‘city full of sanctuaries.’

[[26]]: A local authority.

[[27]]: The founder of Fez, son of Moulay Idriss I.

[[28]]: The main congregational mosque in Fez, one of the world’s oldest mosques, founded by two women.

[[29]]: Titus Burckhardt.

[[30]]: A charitable animal shelter still functioning in Fez, providing care to infirm animals.

[[31]]: The synagogues of Fez have since been restored by the Jewish expatriate community of Fez.

[[32]]: Literally “corner” but here referring to a gathering place of dervishes, Sufis. Each brotherhood in Fez has its own zaouia.

[[33]]: Literally, “listening” to spiritual poems and prayers of benediction upon the Prophet Muhammad.

[[34]]: Plural of faqir.

[[35]]: Oh Lord!

[[36]]: A gathering in Remembrance of God.