For many years before I met Wolfgang Smith, I was well acquainted with his groundbreaking work. I had copies of all his books and articles, and I benefited from them greatly. In 2009, I wanted to ask if he would contribute an article to a book I was editing. Eventually, I was able to obtain his postal address from mutual friends, who told me that he did not use email, and the only way to contact him was by letter. His whereabouts were largely unknown, and scant personal details have been available about him on the internet. He lived with his wife as a recluse—in the world, but not of it, consistent with Christ’s reminder that “My kingdom is not of this world” (John 18:36).

A few days after I wrote to him, I was honored to receive a telephone call from Wolfgang expressing his gratitude for my letter inviting him to submit a piece for the book. It was the first of many memorable conversations. Less than a month later, sometime around March 30, 2009, I was grateful to meet him and his wife, Thea, in person in Ojai, California, which is a little over thirty miles from Camarillo. His wife was an exceptional and talented person, who was very devout in her Catholic faith.

I remember as lunch was served at our table, both he and Thea expressed the need to give thanks for the food that we were about to receive, and so they started to pray over it. The patio of the restaurant was very crowded, yet they undertook their consecration without hesitation. It was a beautiful moment wherein the Divine presence was acknowledged in the here and now. We could not have asked for a lovelier day: it was a truly stunning spring afternoon. Our conversation, which spanned many themes—our sojourns to India, the state of the world, common friends, and essential books—always returned to our relationship with the Lord, as this was the sine qua non of the human condition. After this providential meeting, we had several more telephone conversations and written exchanges.

Wolfgang was born in 1930 in Vienna. Following the outbreak of the Second World War, he and his family fled Austria for the United States. He graduated from Cornell University at the age of eighteen with degrees in physics, mathematics, and philosophy. In very little time, he also obtained a master’s degree in physics at Purdue University. He then earned a doctorate from Columbia University and served as a professor of mathematics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the University of California (LA), and Oregon State University until his retirement in 1992.

He has expressed, on many occasions, how fortunate he was to have created his own mathematical theory of submersions so that he could co-exist but did not have to deal with the polemics within contemporary academia. While mathematics interested him and he had many significant publications in this field, he was more interested in the pursuit of science and metaphysics. Wolfgang discussed the profound isolation he experienced throughout his long tenure as a professor, as he never had anyone that he could call a friend among his colleagues. This left a permanent impression on him, not only about the state of academia, but also regarding the world around him.

Several years later, I was informed by mutual friends that his beloved wife Thea (Dorothy Marguerite Smith, born in 1926) had passed away at the age of 90 on June 21, 2017. I wrote to Wolfgang right away to offer my condolences. He phoned me shortly afterwards and we spoke for a long time about Thea and the significant role she played in his life. Indeed, it was Thea’s influence that helped guide Wolfgang back to the Christian tradition. She had, in fact, spent some seventeen years in the Catholic convent of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet, which she left after witnessing the horrors following the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965), according to the insistence of her spiritual advisor. She informed her husband that “God sent me to the convent in order to catch a big fish”: this, of course, being a reference to none other than Wolfgang himself. We also discussed his new body of work, and the forthcoming full-length film devoted to his life and thought, The End of Quantum Reality, which was released in January 2020.

Wolfgang’s decision to move forward and participate in this project was very much a surprise, given the film’s personal nature and its intimate portrayal of his life and thought. I say this because I had known him to be a very private man who was averse to having the details of his life exposed for public consumption. His decision, however, was a profoundly compassionate offering that is sure to benefit many people. While I was conducting an interview with Wolfgang about this movie, we spent the entire day and most of the night together.[[1]] While we were discussing many important subjects, I recall, at one point, sitting in his lovely living room listening to The Best of Serge Jaroff and His Don Cossacks, appreciating the power and the brilliance of the voices. He had a great love of classical music and, when he could no longer attend concerts in person, he would keenly watch live performances from home.

On many occasions, Wolfgang expressed, in no uncertain terms, that if it were not for Rick DeLano (1957–2022), the producer of the film—who came into his life just as Thea was leaving this world—that he himself would surely have also died shortly after. The grief that he felt was a shattering blow to Wolfgang. It was very difficult for him to envisage a life without—they had been inseparable. His new work, along with the film, conferred great blessings and spiritual strength on Wolfgang, which allowed him to continue in the face of his terrible loss. Apart from her doctorate in mathematics, Thea was also a musician, dancer, and singer—in fact, she wrote a song conveying the great respect she felt for her beloved husband called “Lonely Man,” which was featured in the film. Wolfgang provided the backstory to the song, saying that Thea had gone for a walk one day on their remote property of some twenty-five acres (outside of Corvallis, Oregon). Upon returning home, she told him that the song simply came to her and so she sang it for him.

Although Wolfgang saw metaphysics as something universal and timeless, he always returned to the uniqueness of the Christian tradition and stressed the need to pray constantly by remembering the “one thing needful” (Luke 10:42). He stressed that the Trinity and the Incarnation could not be found in any other religion. He was adamant about this, emphasizing that this unique feature could not be played down, for to do so was to misunderstand Christianity itself. Needless to say, he took to heart the Gospel teaching: “[T]his is eternal life, that they know Thee the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom Thou hast sent” (John 17:3). He felt blessed to have visited Padre Pio (1887–1968) in San Giovanni Rotondo, as he considered him as one of the greatest modern saints of the Catholic Church, and was also privileged to have participated in a public audience with Pope Pius XII (1876–1958) in Rome.

At the age of 18, he frequented meetings of the Vedanta Society in New York, under the tutelage of Swami Nikhilananda (1895–1973). He traveled extensively in India to deepen his acquaintance with the Hindu tradition, and spent time in the company Śrī Ānandamayī Mā (1896–1982), one of the great spiritual luminaries of the twentieth century. Wolfgang was moved by the maxim of the Maharajas of Benares attesting that “There is no religion higher than Truth,” which Nikhilananda wrote in a signed copy of his translation of the Upanishads. For Wolfgang, this confirmed a profound truth that remained with him until his final days. The Christian tradition confirms this powerful statement with Christ’s dictum: “And ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free” (John 8:32).

He spoke with deep disappointment about the death blow that the Second Vatican Council inflicted on the Catholic Church, and was devastated by the fact that the institutional church was on the brink of collapse. He spoke of an esoteric Christianity that was oral, rather than written, which allowed for the transmission of gnosis (transcendent wisdom) as expounded by Clement of Alexandria (c. 150–c. 215)—a faculty of spiritual wisdom unknown to most Christians today. He stressed that both written and oral traditions—comprising the exoteric and esoteric dimensions of the faith—were indispensable.

Wolfgang firmly believed it would soon be time for a new ecclesial body to emerge where the church would undergo a metamorphosis akin to the three stages of the life of Christ. Malachi Martin (1921–1999) referred to the second stage as the “Church of the Entombment” (or underground church), which we are currently in, and called its final stage the “Church of the Resurrection.” He often spoke about Malachi Martin, whom he knew personally, and whose work he considered to be profoundly significant. Wolfgang also took the view that the mission of this new church, along with its Mystical Body, could only be fulfilled when Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy (and the Protestant forms of Christianity as well) were reunited, as both were needed to complete one another—“the Church must breathe with her two lungs” as St. John Paul II once remarked. Only then could there be a truly catholicos or universal Church. This new church would barely resemble how Catholicism is viewed now, because the former would be more mystical in its outlook. Wolfgang recalled that he and Father Martin agreed that the Second Vatican Council is an evil, in response to which it is necessary for the Church of the Resurrection to be realized.[[2]]

Wolfgang made no attempt to gloss over the dark episodes in the history of the Catholic Church. He spoke despairingly of the Inquisition, stressing that it was not only “dreadful” but a “terrible crime!” He often affirmed the motto “The corruption of the best is the worst” (corruptio optimi pessima). In this regard, we recall the following passage from St. Paul: “For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places” (Ephesians 6:12).

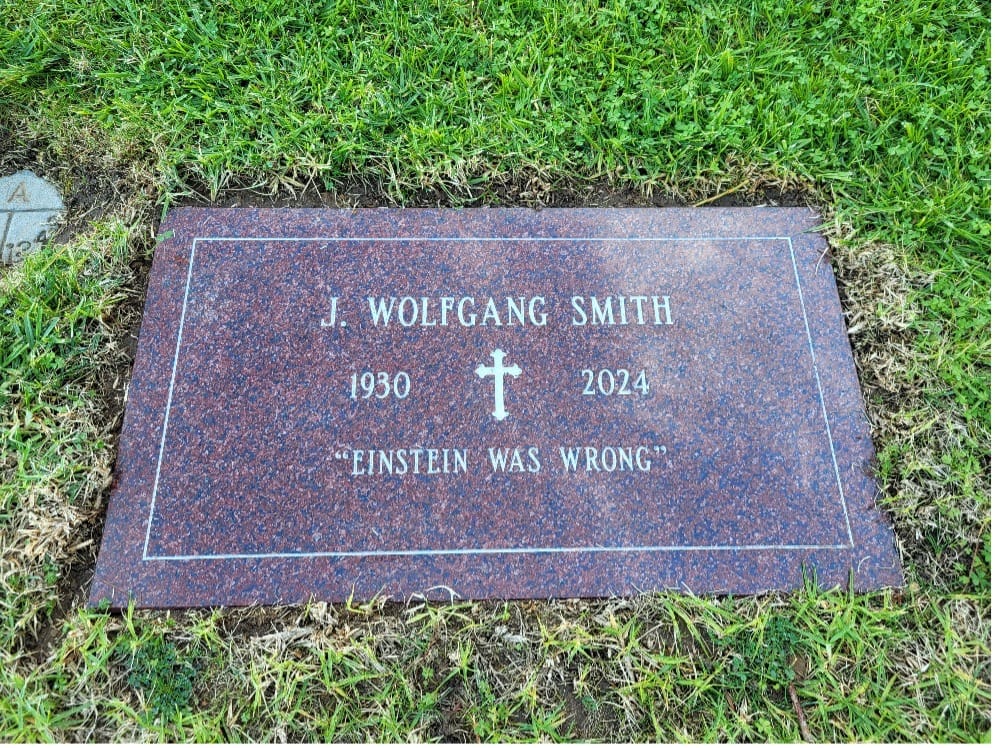

Given his unique perspective as both a physicist and metaphysician, Wolfgang addressed the errors not only of scientism but also (as he understood) of modern science. His insights about the distinction between the corporeal and physical worlds, for instance, led him to critique certain aspects of modern science. His critiques of certain errors of Einstein, for example, are mentioned in Wolfgang’s own publications, and also in my interview of Wolfgang for Sacred Web. While he was an admirer of Einstein and other modern scientists, he was not prepared to canonize them or their views if they did not stand up to integral principles, and he had no hesitation in asserting “Einstein was wrong.” It is a sentiment that now appears on Wolfgang’s grave marker.

I remember having a long conversation with Wolfgang on February 18, 2020—on the occasion of his 90th birthday—and observing how assiduously he was working on his new projects. He demonstrated remarkable energy and commitment in tirelessly pursuing this important work, noting that if he were to stop writing, he would likely breathe his last before too long. Mind you, when I initially met Wolfgang years earlier, he explicitly stated that he was putting down his pen and retiring from writing. Many would be grateful that he did not follow through on this resolution, and it is truly remarkable to see how much more he has accomplished since then.

I once asked how he wished to be remembered, to which he replied: “As a believing Christian.” When asked how he would describe his contribution to science, he said: “When we are born, we have a destiny, a way that we are meant to go; to be true to this or not. My interest in physics and mathematics was something that I was supposed to do. To follow this path—as determined by God—is more beautiful than anyone can imagine.” He again repeated that his task was “to fulfill my destiny.” Wolfgang proved, once and for all, that science disconnected from metaphysics led, not only to an acute imbalance, but to the nefarious ideology of scientism, along with the pseudo-religion of secularized, postmodern humanity. For him, science could only be fully integrated when it returned to its spiritual roots in the transcendent.

In several of our conversations, Wolfgang indicated that he was not sure how long he had left to live, and he had come very close to dying on several occasions (in the Nazi invasion during the Second World War, and on several mountain-climbing expeditions). He valiantly fought through these trials so that he could continue his work. On one of our visits, Wolfgang appeared to be struggling very much with his health. He could barely draw breath, and walking was very difficult for him. I was unsure how long he could endure this condition. Yet, there were moments where he was so vibrant, present, and articulate, not to mention steadfast in his demeanor, that it reminded me of the Wolfgang I had known years before. Regarding what lies beyond the grave, he said that our post-mortem states were an imponderable enigma, about which he declined to speculate.

During the recent pandemic, we spoke frequently over the phone, due to the shelter-in-place order that forced him into severe isolation. He would always say that “this too shall pass,” insisting that we can never give up hope or fall into despair. He observed that, in our most difficult moments, grace is even more abundant—our primary duty, then, is to always seek refuge in God and to pray continually. Throughout this time, Wolfgang told me that there were days when he would barely eat, as he was working almost around the clock, which allowed him to uncover new ground and deepen his insights. So, although this was a very testing time, it was also a blessing because it provided him with the opportunity to bring to a completion his life’s opus. During this uncertain period, he would often bring to mind the following verse: “He that is not with me is against me” (Matthew 12:30), indicating that we all have a choice to make in this earthly existence and that, unless we conform our will to God’s, we are—knowingly or unknowingly—working against Him. Wolfgang never failed to place his trust in God, saying it was imperative that we live a prayerful and contemplative life.

During the COVID crisis, he felt the need to partake in the Eucharist regularly, to keep him “in a state of grace,” and he reflected on how ominous it was that God’s churches were closed down due to the lockdown, especially at a time when people most needed access to them. His prayer was heard as he was able to find a priest who invited him—in secret—to attend Mass during the pandemic. He was truly grateful for this and celebrated these occasions with great joy. When the churches finally reopened, he lamented that Holy Communion could no longer be given directly on the tongue; he considered Communion on the hand to be a diabolical subversion.

Wolfgang noted that the forces of darkness were very powerful in our time and that, while these liturgical restrictions were touted as a public safety measure, they were nonetheless a pretext to undermine the traditional Catholic Church. Through an underground network, he was able to make contact with other priests who were also offering the traditional Mass in the correct manner (albeit clandestinely). All the while, he never forgot these comforting words: “I am with you always, even unto the end of the world” (Matthew 28:20). Needless to say, he gave thanks when he was able to return to St. Mary Magdalen’s Chapel, where he could, once again, attend the Tridentine Mass and receive the Sacred Host on the tongue as he was previously able to do.

He imparted the advice, on several occasions, that when it comes to our spiritual life, we need to “read selectively,” which was an important lesson for him to learn as, early in his life, he read everything of interest that he could get his hands on. He added that “one will drown no matter how far they can swim; you cannot reach the shore because there is no way to assimilate it all.” For this reason, he had learned—through the course of his long and blessed life—that what was of utmost importance was to focus our spiritual life on Christ, in order to return to God.

In March of 2023, Wolfgang came close to dying when he took a very bad fall down the steps of his two-story home, hitting his head and breaking several ribs. Although he was able to do some writing following the accident (in order to complete the publication of his collected works through the Philos-Sophia Initiative), he told me many times that he had not fully recovered from this incident. On Christmas Eve of 2023, he suffered another serious fall, which then led him to be placed in an assisted living facility to support his increased needs. It was at the end of May 2024 that I was able to visit Wolfgang for the last time prior to his repose in his Lord on July 19th, 2024.

Wolfgang was exceptionally serious in his demeanor, and had a razor-sharp intellect. He was also a very eloquent wordsmith, always being mindful to communicate in a precise manner by using words correctly. He was—without fail—the perfect gentleman, extending graciousness and generosity towards everyone. Wolfgang was a man of another age, as was Thea: an age that has been long forgotten by the world today. He always felt blessed to have lived as long as he did, and believed that this could not have been possible unless God had willed it.

Wolfgang spoke of the importance of love. Insisting that love was not just a sentimental notion but a way of life, he cited the adage Deus Caritas Est (God Is Love), underlining that all things are embraced in the Divine mercy. This is taken from the verse “God is love; and he that dwelleth in love dwelleth in God, and God in him” (1 John 4:16).

[[1]]: See Samuel Bendeck Sotillos, “The End of Quantum Reality: A Conversation with Wolfgang Smith,” Sacred Web: A Journal of Tradition and Modernity, Vol. 45 (Summer 2020), pp. 48–65

[[2]]: See Wolfgang Smith, In Quest of Catholicity: Malachi Martin Responds to Wolfgang Smith (Brooklyn, NY: Angelico Press, 2016)