Introduction: The Significance of “Corn”

In March 2006, while we were standing on top of the First Mesa in

northeastern Arizona with the villages of Walpi to our right and Polacca

spread beneath us, a Hopi Indian friend told me “corn is our life.” In this, he was echoing what Charles Talayesva, born in 1890, had reported as a common saying in his childhood: “corn is life.”[[1]] Connections between humans and corn abound in Hopi culture. These include such sayings as “the people are corn,” “corn is a maiden,” “corn is our mother”; an identification between various human body parts and physical elements of corn plants; and the fact that newborns are even cradled with an ear.[[2]] These expressions and practices all show the extent of the relationship between corn and Hopi identity.

The emphasis upon corn goes back far beyond a mere hundred years, first into a thousand plus years of historical time into a mythical past when the Hopi emerged from underground into the fourth world, chose a small, sturdy corn as their staple and were given use of their high-desert homeland.[[3]] In Hopi cultural practice and religious belief not only was corn the staple food; it is the symbol of the Hopi people in most religious ceremonies and practices.Thus the Hopi use cornmeal in almost every ritual, and also use it to feed ritual masks. Everywhere from humble cornfield shrines to dances, Hopi sprinkle finely ground cornmeal from small leather bags in a request for blessings. Corn represents the coherence of the Hopi way of life, as in it meet both the needs of sustenance and cultural-religious goals. As Alfonso Ortiz and Richard Ford have pointed out, this emphasis upon corn is part of a larger Pueblo Indian cultural pattern, of which the Hopi are but the westernmost example.[[4]]

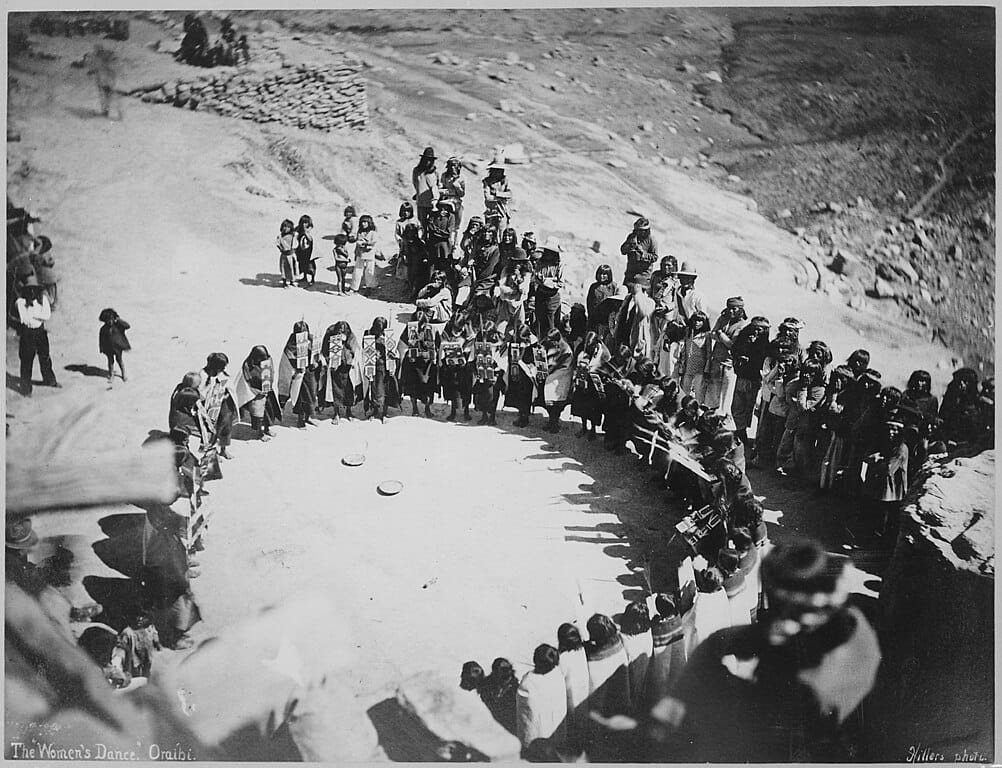

Hopi spiritual practice involves an elaborate year-long cycle of rituals, many of which center on the necessity of rain in an arid landscape, as well as on the spiritual or symbolic meaning behind this rain’s continued presence. The cycle partly focuses on katsina or kachina spirits, deities identified with clouds and ancestors who confer blessings on the Hopi people, and who in February return from their winter home in the San Francisco mountains near Flagstaff, Arizona, some hundred miles southwest of the mesas. From March until a final ceremony in late July dictated by the maturity of the corn’s growth, when the Niman or home dances at each village mark the kachinas’ departure for their mountain home, there is an elaborate and complex interweaving of planting, rain, and kiva ceremonies, supported by public dances in village plazas. These kachina spirits bring rain and generally require propitiation in the form of harmonious life and a continuation of traditional ceremonial practices, without which their blessings will cease. This religious practice is highly participatory, in that many members of various clans have inherited responsibilities for the execution of ceremonies. As Hopi children mature into young adulthood, they are initiated into full participation and accept the responsibility for carrying on ceremonies and embodying Hopi values.

What marks traditional Hopi life, then, is a holistic pattern in which

subsistence agriculture, especially of corn, human disposition and conduct, communal, clan-based ritual and economic activity, and the natural cycles of weather—the sun’s movement, the wind’s breath, winter snowfall, summer rainfall, seasonal alternation—are thoroughly interwoven into a seamless whole. In the traditional ideas of the Hopi, there is little or no distinction between mundane and sacred pursuits. The Hopi have carried out their farming in a landscape seemingly illsuited to agriculture.This area, southward reaching fingers of the Black Mesa and the valley lands below them, features cold winters along with frequent summer drought, with only about 130 frost-free days per year, and a mere ten to twelve annual inches of rain. While the Hopi are famous for their ceremonies, which often end with a public dance, even the planting of corn, the clearing of the fields for planting, harvesting, and the preparation of food are traditionally significant ritual acts. Farmers’ fields still reveal small shrines sprinkled with corn meal and adorned with spruce boughs and prayer feathers from kachina dances; in helping a friend weed his cornfield, I have watched him and his children sprinkle cornmeal at such a shrine after the previous day’s dance.

Underlying this life of farming is a profoundly symbolic and theological understanding of desert agriculture and its necessities: the sun, corn, and rain.The brief and erratic summer monsoon season, from July until September, and the resulting intermittent rainfall—a tangible grace that strikingly and visibly falls in one area while leaving others dry—ideally results in the growth of hardy strains of indigenous corn, which is in turn central to Hopi religious practices and at least traditionally to Hopi physical survival as well, for it once provided the main physical sustenance to a tribe that was historically vegetarian except for very small amounts of hunted meat.[[5]]

In this setting, corn’s healthy growth and an abundant harvest is a sign that people have maintained the correct inner dispositions for rain to fall in the correct amounts and places. Corn was a necessity for life, which is one meaning of the quotation that began this essay. Nor is this life only the physical or corporeal, as some anthropologists claim--they maintain that Hopi religion is a primitive substitute for “scientific” control of the “material” world.[[6]] Rather, it is life both corporeal and spiritual. Likewise the famous rain dances that typify Hopi and pueblo culture in general in the American Southwest are “for rain” in a manner that scientific, materialist, post-Enlightenment Euro-American thought finds hard to understand. For “moisture” is much more than physical water; it is has a spiritual significance:

Breath, moisture, cloud, and fog have all been referred to by the Hopi in describing the spiritual essence of the universe. Moisture, or rather a certain aspect of moisture, is perceived by the Hopi as the “spiritual substance” of the cosmos and receives a name kept secret from the uninitiated. In fact, a primary purpose of the initiation of all Hopi youths into the Kachina cult is to inform them that the spiritual substance is their origin, nature, and destiny.That the cosmos was created and sustained by the spiritual substance is common knowledge among adult Hopis, a position perhaps best revealed by their emergence mythology.[[7]]

Such concepts are difficult for contemporary Euro-Americans to understand, as Enlightenment cultural assumptions orient its members toward believing only in matter and motion as adequate explanations of all phenomena for the secular, or at least of all natural phenomena for those who consider themselves religious. Even those moderns who do not believe in the exhaustiveness of materialist assumptions, regard farming largely as a practical matter, concerned with the mundane and not the sacred.[[8]] In contrast the Hopi have a strong, indeed pervasive, sense of the sacred, and this sense is never divorced from mundane

pursuits. For instance, one morning after a summer monsoon rainfall had left a pool of water in a plastic tarp in his cornfield, a Hopi friend called his children outside to anoint themselves with the rainwater, visibly acknowledging its sacredness.

This spiritual importance of both corn and moisture leads to another observation: agriculture in the traditional Hopi view involves a submergence of the farmer in a timeless world of ritual and myth. It is not merely an economic or subsistence activity undertaken out of physical need. This is especially true of farming as practiced before the rise of a mixed economy, when clan lands, group planting and harvesting, and planting schedules defined by ritual all helped cement the connection between mundane farming, the emergence and migration stories, ritual, and the planting, germination, and growth of corn.[[9]] This becomes even clearer when we consider traditional Hopi ideas about how plants grow. For while Euro-American ideas on plant biology are grounded in empirical science, a product of the Enlightenment, Hopi ideas stress factors beyond the material in germination and growth. Muyinwa, the deity who controls germination, makes sure that the correct plants come into being by taking the correct plant from his own body.[[10]] Thus plant growth is not based upon mechanistic understandings of cells and DNA, but on moral and spiritual understandings of how origin myths, ritual behavior, correct intentions, and other factors combine to form a healthy crop.[[11]]

This pattern is a beautiful but threatened one, as the Hopi become more integrated into the dominant culture that surrounds their once-remote home. How and why this connection has changed in a world where foods, including corn, have increasingly become commodities is my subject. In the early 21st century, Hopi cultural and religious practices, tied as they are to a subsistence agriculture based upon a worldview that acknowledges no separation between religion and agriculture, spiritual and physical sustenance, face serious challenges. Through comparing the distant historical past of Christianity to the current realities of the Hopi, I hope to clarify both and come to a greater understanding of the relationship between modernity and pre-modernity. I also hope to provide the beginnings of a nuanced understanding of the use of corn as Hopi symbol as it applies in a post-subsistence-agriculture world.

Modernizing Influences Among the Hopi

Until a little over a century ago, the Hopi people constituted a pre-modern society that existed on the far western margins of the Euro-American culture and its social norms. As pre-modern, Hopi cultural values were spiritual and symbolic rather than scientific, conservative rather than embracing rapid change, and were focused upon a holistic view of human beings within their natural environment rather than the mechanistic, human-managed view of the natural world as inert matter to be manipulated to satisfy human wishes which has typified Euro- American attitudes since the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Though the last century and a half have brought unprecedented change, the Hopis remain the North American people that has most successfully maintained its traditional religious practices.

Despite their religious and cultural conservatism, the Hopi have over the past one hundred years faced immense pressure from the dominant culture in both overt and subtle forms.The overt forms have been well documented, and include a history of forced education and Christian catechization, the banning of traditional religious practices, the suppression of the Hopi language and even of traditional hair styles, and other such “mainstreaming” practices that aimed at making Indians a thoroughly interchangeable part of mainstream Euro-American culture, marked off only by cultural origins, not by practices or beliefs.[[12]] The more obvious forms of overt pressure have disappeared, but subtle ones have remained and intensified. The Hopi’s increasing participation in the larger commodity-based economy around them represents an even greater threat, for unlike government or missionary attacks on language and customs, these come in the agreeable guise of consumer choice. Nearby Wal-Marts and the satellite television (available through dishes dotting Hopi lands) represent a greater and more pervasive force than the US government’s presence in Keams Canyon ever did. As Frederick Dockstader wrote in 1985,

The mundane world to which the kachinas return annually has changed radically. The Hopi now live completely in a cash economy, dominated by White financial and political interests. They report to a wholly different calendar, dictated by the five-day, 9-to-5 routine, working primarily for federal, state, or local governments, reservation industries, or in clerical or labor capacities in neighboring small businesses. Farming has decreased in acreage, since with a cash economy, it is easier to buy corn at the store than grow it. In 1882, approximately 5,000 acres were regularly worked; today, this number has declined to about 3,000 acres.[[13]]

Dockstader’s claim that Hopi now live in a wholly cash economy is perhaps somewhat overstated, for corn continues to be cultivated in fields of significant size. But while he may have expressed this central change in Hopi economic life in too categorical terms, the shift itself has certainly affected both people and land on the reservation.[[14]]

This shift has had consequences. John Loftin wrote fifteen years ago that one Hopi from the third mesa claimed that there the ceremonies were now cultural and not religious.As cause for this shift from sacramental to cultural, Loftin notes that traditionally “the Hopi ceremonial cycle is inseparably linked with traditional Hopi subsistence activities, such as farming. One old Hopi man confirmed the relationship of farming and ritual when he asked,‘How can you pray for rain if you don’t have a field?’”[[15]] Loftin’s passage reveals the problem: when, as is so in the case of the Hopi, a religio-cultural system is bound up with a traditional means of livelihood, rendering subsistence activities themselves sacred and ritually significant, any change in these means of livelihood involves the possibility that the religion itself will decay. Hence the above claim that Third Mesa ceremonies have become merely cultural.

So an immense change has taken place in the past century. In the middle to late nineteenth century, Arizona was a frontier territory and the Hopi were off on the remote margins even of this sparsely settled area. Consequently, the tribe’s traditional mode of life could continue. But America’s transformation of its new territory was much more aggressive and rapid than the Spanish colonizing ever was. Within about fifty years of American control the railroad had arrived a mere seventy miles south of the Hopi mesas, and tribal artists, crafts, and cultural

productions became attractions that the railroad used to market travel

and tourism.As early as 1897, the Santa Fe Railroad began using “Indian

themes”to promote Southwest travel and tourism, and provided instructions on how to get to the Hopi mesas for “the famed Snake Dance.”[[16]] Not long after the end of the Second World War came paved highways running past the three mesas, putting them a mere one and a half to three hours from Winslow, Flagstaff, and Gallup.[[17]] Bureau of Indian Affairs high schools in Santa Fe, Phoenix, and Riverside exposed young Hopi to the dominant culture as well as to other tribes, and the first Hopi high school other than the Bureau of Indian Affairs School in Keams Canyon only arrived in the late nineteen eighties.

The paved highways through the reservation integrated the Hopi reservation more fully with the Euro-American society outside.A trip that had taken a day over dirt roads (more in the age of the horse-drawn wagon) could now be done in mere hours; shopping off-reservation became more and more commonplace, and opened up the panoply of choices available in consumer capitalism to the Hopi, as well as Hopi lands and people to travelers who no longer had to brave dirt roads and washes that flooded during the sudden rains.This cultural integration became even stronger with the advent of electricity and television. Up until the late 1950s, even Kykotsmovi, the village that is home to tribal government offices, had no electricity.[[18]] Now, on the three mesas, only the villages of Oraibi on the Third Mesa and Walpi at the end of the First Mesa do not have externally supplied electricity (though gasoline generators are common in Oraibi); and in the other villages, small satellite dishes deliver a multitude of television channels into homes, which range from traditional hand hewn stone, to US government-sponsored cinderblock, to prefabricated trailer homes in the villages below the mesas. In August 2006, I watched cable news coverage of Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in a friend’s house in Polacca on the plain below First Mesa, and during the same visit, my friend’s children watched cartoons on a children’s cable network. The media and the advertising that come with it are far more inexorable than even the United States government could ever be, and as a result the Hopi diet has changed, as have the economic activities that support this diet. Sodas have replaced rainwater; snack foods and store-bought bread have replaced piki; and to support these changes, jobs have replaced subsistence agriculture.

Given the shifts in the years after the Second World War up to the present, there has been a significant decline of farming as the Hopi integrate into the dominant culture’s wage labor and cash economy.

This shift away from subsistence farming, which has accelerated significantly in the past forty to fifty years, also affects religion because of the interwoven symbolic value of corn, rain, religious practices and overall human disposition in Hopi culture. Conversely, ancient cultural and ritual patterns cannot easily adjust to wage labor.These facts make Hopi beliefs and practices difficult to hybridize with the values and orientation of the dominant culture.

The Hopi Worldview and Practice

This split between the world the Hopi now inhabit and the world of inherited cultural norms might at first glance seem unbridgeable. The dominant culture world of globalized consumer capitalism rests on profoundly individualistic assumptions, whereas Hopi culture is intensely communal; the modern world is time bound; the Hopi strives for timelessness.There are many such contrasts. But the Hopi are also immensely flexible. Despite corn’s shrinking importance in Hopi sustenance, it remains central in other respects. Beliefs concerning corn and its growth still guide Hopi actions. For example, in the summer of 2006 Leigh Kuwanwisiwma, head of the tribe’s Office of Cultural Preservation, described how a Colorado university asked permission to do research upon how various kinds of corn might grow in Hopi lands with and without irrigation.The tribe asked the advice of various elders, whose answer was “no.”Their reasoning was that “you do not experiment upon your children.” For the Hopi corn remains much more than a manipulable commodity; it continues as a spiritual substance with a metonymic relationship with the Hopi people.

This identification between people and corn shows itself in other ways as well. In 2006, a Hopi friend who farms corn told me that “if people planted in the right way, there would be rain.” His words suggest that the growth of corn makes visible the spiritual state of the farmer. His ideas also invert the dominant Euro-American paradigm that acknowledges only material causes, consigning teleology or final cause to the subjective realm. These examples reveal how the whole Hopi worldview involves a pervasive denial of the mind-body split that defines modern Euro-American culture, for the growth of plants is here reliant upon inner human disposition, not external factors. Additionally, it goes even further in its integrative and holistic view of reality than did pre-modern European thought, which still emphasized binary soul-body and form-matter divisions even as it allowed for profound interpenetration of spirit and matter.This worldview covers more than Hopi ideas about corn. Instead, personal and communal internal dispositions have a pervasive influence, and Hopis in general are supposed to keep an appropriate inner orientation of humility and peacefulness in order to ensure that the rain falls, the plants grow.[[19]]

We might expect the decline in subsistence farming to result in the destruction of Hopi religion. Perhaps the most famous anthropologist to study the Hopi, Misch Titiev, wrote in 1944 that

[s]horn of its elaborate, detailed, and colorful superstructure of costumes, songs, and dances, the entire complex of Hopi religious behavior stands revealed as a unified attempt to safeguard Hopi society from the danger of disintegration or dissolution.

By itself, this statement seems undeniable. But Titiev continues by claiming that the Hopi“seek to guarantee their stability and permanence; and lacking material means to counteract the effects of a hostile environment or the inescapable ravages of death they turn to the supernatural world for assurance that they will not be destroyed.”[[20]] For Titiev, Hopi religious ritual was a primitive substitute for modern empirical science and control over nature. Lacking scientific method and the ability to manipulate their environment, the Hopi fall back on the “supernatural world” for their “assurance” instead.

There are numerous problems with Titiev’s interpretation of the Hopi religion. The most basic of these is its reductiveness based upon Titiev’s assumption that the Enlightenment scientific viewpoint—that matter and motion alone are real—is the telos towards which“primitive” religion aspires. But more importantly, Titiev’s view does not support what has happened in the years since he made his observations. Given his statements of some sixty plus years ago (which were in turn based upon trips to Hopi in the 1930s, seventy plus years ago), we would anticipate that upon the Hopi entrance into mainstream society through participation in Euro-American education, traditional religion and culture would fade away. This has not happened; the materialist explanations of modern science have not displaced traditional beliefs and practices. Instead, the tribe’s Office of Cultural Preservation invokes traditional ideas in its response to Euro-American scientific research queries. Both Hopi institutions and individuals have learned to compartmentalize, working to discern those valuable parts of the dominant culture from the destructive, and accepting the former while rejecting the latter. Instead of modern science posing a threat to Hopi belief and practice, it is paradoxically the internal logic,the very interrelatedness and coherence of Hopi belief that has posed the greatest threat to religious practice. For if farming corn is the basis of much of Hopi religion, the religion itself is affected when this foundation is displaced by the inexorability, the sheer ubiquity of the commodity marketplace.

So instead of the abstract lessons of empirical science killing off Hopi ceremonies, we find that the greatest threat to Hopi traditional religion comes from the severing of economic life from spiritual.The danger lies in what happens when most of the food consumed comes from retail outlets, whether small markets on the Hopi reservation or larger supermarkets and big box stores in the surrounding towns of Gallup, Winslow, and Flagstaff. Richard Clemmer claims that as of the 1990s, “80% or more [of Hopi] food [came] from grocery stores rather than from field and pasture.”[[21]] This shift is significant, for as we have seen, Hopi society is based upon a complete integration between the mundane and sacred. One possible result is that the ceremonies and dances become cultural rather than religious: they embody enduring values that split off from everyday life.That is, they are still considered important, but as aspirational rather than as actually functional in meeting the combined physical-spiritual needs of the community.As Peter Whitely stated some twenty years ago,“where the symbolic connection between corn and human life was previously founded in the sheer conditions of existence, it [the farming, especially of corn] now has become a more abstract statement of Hopi ethnicity.”[[22]]

This shift in livelihood and practice effects shows itself in strange ways. At kachina dances in 2006 and 2007, a Hopi friend speculated on the increasing effects of status-seeking on behavior. Dances, he said, have become much more a way of establishing social status, of being seen, and of parading fashion and affluence in a manner at odds with Hopi values of humility and group identification, especially as Hopi who live outside traditional lands come back for dances.This is perhaps one way that integration with the dominant culture’s patterns—of individualism, of status-through-consumption—is changing the background texture of Hopi life.The tribe’s generations from middle aged to older has seen a shift from a mixed economy that included a significant percentage of subsistence desert agriculture supplemented with wage labor cash into a modern one in which wage labor predominates, while corn and its cultivation now have a metaphorical rather than subsistence importance. Corn has gone from a symbol to a metaphor; from a physical necessity that simultaneously embodies deep metaphysical meaning to something required for religious practice, but that is increasingly divorced from the mundane realities of Hopi life.The separation from farming for corn based upon the tribe’s integration with the dominant American world of wages and purchased food involves much more than a shift in some secular livelihood might mean to modern Euro-Americans.

The Hopi themselves of course realize this shift. For this reason, many Hopi who are full members of the wage economy continue to farm on a limited basis. A young tribal government employee, a graduate of Northern Arizona University, described how while Navajo and Euro-Americans enjoyed “recreation” on weekends—that is, the spending of their wage surpluses in modern patterns of consumption—he instead often tended his corn crop because of the centrality of both corn and its cultivation to his Hopi identity. A second older government employee indicated how he too still farms, despite his full time job with the tribe.

A good Hopi friend in Polacca whose livelihood comes mostly from making and selling pottery likewise farms, and tries to inculcate in his children, nephews, and nieces the importance of this farming to his and their Hopi identity. But despite his corn, squash, and bean fields and his ideals, his daily food is largely bought with cash rather than grown from stored seeds.

Sentimentalism and Secular Space

In this supplanting of indigenous foodstuffs and of subsistence agriculture among the Hopi by mainstream purchased foods and the wage economy, one danger lies in a profound split between ideals and realities that lead to sentimentalism as a feature of contemporary Hopi culture. This pattern is certainly not unique to the Hopi, for it took place in Christianity over several centuries as well; but an incredibly accelerated time frame distinguishes this more recent shift. Ann Douglas has written on the uses of sentimentalism in the transformation of New England American Protestant culture in the 19th century. Perhaps such a pattern may now take place within Hopi culture as well. She defines sentimentalism as

a complex phenomenon. It asserts that the values a society’s activity denies are precisely the ones it cherishes; it attempts to deal with the phenomena of cultural bifurcation by the manipulation of nostalgia. Sentimentalism provides a way to protest a power to which one has already capitulated. It is a form of dragging one’s heels. It always borders on dishonesty but it is a dishonesty for which there is no known substitute in a capitalist country.[[23]]

Nineteenth-century American Protestant Christianity needed the mechanism of sentimentalism to bridge, however imperfectly, the gulf between the society’s economic and cultural norms and its religious ones. This same Euro-American culture formed the dominant culture in which the Hopi are embedded; and it now even less allows for unchanged practices such as subsistence farming of corn within an ancient religio-cultural framework.While individuals and groups may wish to hold themselves separate from the dominant culture, actually doing so is incredibly difficult.

To give but one simple example of this difficulty, consider dominant-culture education. Practically no-one would deny the Hopi’s need to ensure the education of the youth so as to allow them some degree of participation in and control of, at however distant an arms length, the larger world.Tribal interests in ongoing land disputes, the repatriation of cultural artifacts, and in questions about mining and natural resources on reservation land all require professionally-educated members of this society. Yet this need, and many others that are equally important, have ensured that Hopi youth absorb the norms of the larger culture, in whose systems of higher education they must submerge themselves. Yet the communal needs themselves all imply that some degree of a split between Hopi ideas and realities is inevitable, resulting something like the“secular”space of that exists within contemporary Christianity, or indeed almost any religion that exists in a pluralist, market-based contemporary society.To put it another way, the world of commodity

allows no exceptions apart from such problematic mechanisms as sentimentalism.This mechanism is now as essential to the Hopi as it was to the 19th century New England Protestantism that Douglas studied.

But we can move further back than 19th century American Protestantism in our attempt to understand the shifting internal landscape of the Hopi two centuries later. In his book analyzing gift-based versus commodity-based cultures, Lewis Hyde argues that the modern world of capitalism was made possible precisely by the carving out of an amoral “secular space”in which economic activity could take place unimpeded by earlier ambivalences towards profit and usury.Writing of medieval European Christianity, Hyde claims as follows:

The image of the Christian era would be the bleeding heart. The Christian can feel the spirit move inside all property. Everything on earth is a gift and God is the vessel. Our small bodies may be expanded; we need not confine the blood. If we only open the heart with faith, we will be lifted up to a greater circulation, and the body that has been given will be given back, reborn and freed from death.The boundaries of usury are to be broken wherever they are found so that the spirit may cover the world and vivify everything.The image of the Middle Ages is the expanding heart, and the deviant is the “hard-hearted” man.[[24]]

In this passage Hyde presents the ideal of pre-modern Christianity, which was often itself somewhat local and agrarian.This form of Christianity could not continue as the Reformation changed facts on the ground, resulting in changes in emphasis if not in belief. As Hyde indicates,

[t]he Reformation brought the hard heart back into the Church. In a sense, the swing from gift to commodity recrossed its midpoint during these years, the high liveliness of the Renaissance.The Church still affirmed the spirit of gift, but at the same time it made peace with the temporal world that limited that spirit as it grew in influence.[[25]]

Individualism, protocapitalism, commodification: these ensured a split between religious ideals and cultural realities. There was now a “temporal world,” an economic sphere immune to the spirit, which is to say a secular world.

Nor did the process of commodification end with the Renaissance and its hybrid, the early modern world. For as modernity loomed,

the heart continued to harden. After the Reformation the empires of commodity expanded without limit until soon all things—from land and labor to erotic life, religion, and culture—were bought and sold like shoes. It is now the age of the practical and self-made man, who, like the private eye in the movies, survives in the world by adopting the detached style of the alien; he lives in the spirit of usury, which is the spirit of boundaries and divisions.[[26]]

In the threefold distinction between Medieval Christianity’s “bleeding heart,”the bifurcated heart of Renaissance Christianity, and the hardened heart of modern Christianity, we reach the inevitable time of modern sentimentalism as Douglas envisaged it, but now applied to Hopi religion in the early 21st century. In Douglas’ scenario, New England in the 19th century was a place and time where religious beliefs upheld ideals of universal brotherhood and sisterhood and the free flow of charity, while economic beliefs instead demanded competition, hard-heartedness, greed, and the relentless private hoarding of capital. The Hopi, a society based emphatically upon gift rather than commodity, are currently at something analogous to the second phase of Hyde’s characterizations of Christianity, or perhaps the earliest stages of Douglas’ New England.[[27]] At this stage in Christianity the gulf between ideal and reality, gift and commodity, exists but is less pronounced than it later became. In the Hopi’s later iteration of this pattern the gulf also continues to grow as culture and entertainment become more identified with monthly-subscription satellite television and mass media: on Hollywood DVDs and rap and reggae CDs, rather than the indigenous, participatory culture and religion of the kachina and social dances, society initiations, and other gift-oriented forms of meaning.[[28]]

Douglas’ and Hyde’s ideas illustrate just how the Hopi are experiencing in a much-speeded-up present—in perhaps a hundred or a hundred and fifty years—what Christianity experienced over four to six hundred years, from the later Middle Ages to modernity.Their ideas show that while the Hopi are largely immune to the challenge to their beliefs posed by empirical science, they are less capable of resisting the market forces that are the more indirect but far more insidious product of this desacralized worldview in which matter is inert and infinitely manipulable to meet human needs. So what we now see in Hopi life is the growing separation of the religious from the mundane spheres, resulting not from the shedding of or any conscious disbelief in traditional ideas or dogmas, but rather from the Hopi’s economic integration with the dominant culture.The market is far more inexorable and far more ubiquitous than abstract considerations of material and efficient scientific causality.

Thus market forces, made inevitable through the decline of farming and the spatial integration of the Hopi mesas into the dominant society’s physical and cultural realms has resulted in the rise of what we might term “secular space” within Hopi life, as the completely integrated traditional modes of subsistence agriculture, where religious practice and habits are no longer the yeast that suffuses the whole cultural dough, but are instead held to their own privileged and constricted space. Outside this traditionally defined area (which is truly now only traditional, as the very existence of boundaries between sacred and mundane precludes the holistic uniting of agriculture and religion) is an indeterminate mixed area, a confused and contested space where modern a modern ethos of media, market values, wage labor, commodity food, and a much more traditional, communal, and participatory ethos blend and compete.The observation of the agrarian cultural critic Wendell Berry,“[i]f you can control a people’s economy, you don’t need to worry about its politics; its politics have become irrelevant”[[29]]—in other words, economic forces trump politics—is true here, particularly if we switch the word “religious beliefs” for “politics” and make Berry’s claim slightly less categorical. Thus, the Hopi experience would suggest that if one controls a group’s economy, its integrated religious beliefs will lose their full force, though not to the point of making religion “irrelevant.”

While this comparison to Christianity is valid, there are some real differences.[[30]] Christianity in its origins syncretistically inherited a considerable degree of ambivalence about the material world from Greek Platonism and Neoplatonism, in which form is real and matter unreal. This philosophical background, so central to the Western intellectual tradition, perhaps had the effect of predisposing Christianity towards some degree of secular space from its very origins. For while the idea of the Incarnation—of the divine fully and substantially coexisting with matter while not supplanting it—suggests a radical break with this Greco-Roman past, in actual practice Christianity absorbed many pre-existing ideas from the surrounding cultures. So while Douglas’ and Hyde’s ideas are helpful in understanding current trends in Hopi religious life, an accurate picture also demands we respect the differences between what Hopi religion has undergone and what pre-modern forms of Christianity underwent many centuries ago.

“Symbolic Corn Fields”: Modernism and the Decline of Symbolic Content

I hope we can draw from this picture some tentative general conclusions on how pre-modern beliefs and cultural practices change; how the larger modern/post-modern world effects those peoples who actively resist assimilation to Euro-American beliefs. Despite claims about Hopi religion as primitive proto-science, the intellectual chasm between primitive and modern ideas, accounts for a lesser amount of cultural change.The very explicitness of the differences between Hopi belief and those of modern science makes modernity in this latter form much easier to reject.This fact is not that surprising, considering that significant groups (those whom I term “pre-modern hybrids,” namely the adherents of non-reformed religion and to some degree evangelical Christians) within the dominant culture also selectively reject certain “normative” views due to their own beliefs. In comparison to the ideas of science, market forces in the form of job-based labor, purchased food and mass media, especially television, are much harder to withstand. The advent of food as easily purchased commodity, along with the job-and-cash-based economy that allows its purchase is what affects the Hopi religion most strongly.

Where do these market-based transformations leave such groups as the Hopi? Many Hopi want television, and television has immensely negative consequences for traditional oral cultures. This is undeniably true, but if the person making this observation is unable to break this form of the media’s grasp, it should not be surprising that the Hopi likewise lack the ability. This also holds true regarding snack food rather than indigenous corn meal, soda rather than rainwater: the transition from subsistence agriculture to food-as-commodity is an old one in the dominant-culture world of Euro-America; how can even the disenchanted members of this society expect the Hopi or anyone else to withstand what they themselves cannot?

Subsistence agriculture is dead, except for in a few remote spots on the globe that are becoming less remote by the day.A Hopi—or even a Euro-American could, if possessed of heroic strength of will, go against the movement of the age and farm in such a way; but no matter how authentic such a practice was, it would at its root be different from the Hopi agriculture of 200 years ago.This is because it is not only the material practice that makes Hopi subsistence agriculture what it is; it is the mentality that underlies it, and this underlying mentality has necessarily changed over the past 150 years.The very awareness that there were other ways of maintaining a livelihood changes the embodied character of the practices themselves; self-conscious subsistence agriculture is not traditional subsistence agriculture, even if it might look like it to the camera lens. Similarly, anyone who practiced its forms now knows that the degree of social control we exert over the non-human world has changed dramatically as well, so that corn crops may fail and drought might strike, but human beings do not necessarily starve just because of such obstacles, at least not in the short term.[[31]] In this modified awareness, the understood impact of the rites and behaviors that bring rain must also invariably lessen, as will the holistic and synthetic views of moisture and corn as crucial spiritual substances. This lessening give rise to what we might call the “symbolic corn field” among the Hopi, one that provides sustenance in the form of religious and cultural meaning rather than in the form of physical nourishment. These fields are at least somewhat distinct from what we might call “subsistence-symbolic corn fields,”ones that were simultaneously physically and symbolically necessary. Symbolic corn fields dot the reservation; in fact one might argue that there are very few if any subsistence corn fields left.

Thus the “symbolic corn field” is a paradoxical sign for Hopi culture. Its presence simultaneously gives witness to corn’s continuing power as spiritual ideal for the Hopi. But its symbolic importance rather than its simultaneous symbolical and subsistent import—that it is important much more as a cultural/religious idea than as both this idea and as the centerpiece of Hopi sustenance—reveals a significant and growing crack in the holistic/synthetic ethos of Hopi religion.Corn has “fallen”to symbol, rather than having remained timelessly “sacred-necessary” for every aspect of Hopi life; and this “falleness” is itself a sign of Hopi hybridity, of the often uneasy accommodation that has taken place within the last hundred years between two worlds, two identities, two cosmologies. Corn has lost the characteristic of “metaphysical transparency” that so typified mundane Hopi life in the pre-contact era, and all the way up through the second half of the 19th century.

In this change we see the immense power of the marketplace. For my part, I realize that such changes are inevitable, yet it is with real sorrow that I see them taking place. One cannot read the history of the Hopi in the past 150 years without realizing how fragile was the balance on which their desert subsistence farming rested: famine was often a mere two or three arid years away, and was brutal. This threat is gone. The changes of the past century lead to the inevitable question: is physical safety, from famine, for example, always purchased at the cost of some degree of spiritual decline? The asking of this question is possibly more important than any conceivable answer; and perhaps the example of what an integrated worldview looks like can be something of great value even to those whose lives, history, and beliefs are far away from northeastern Arizona.

This article originally appeared in Sacred Web 22.

[[1]]: Don Talayesva’s autobiography is Sun Chief: The Autobiography of a Hopi Indian, edited by Leo W. Simmons (New Haven:Yale University Press, 1942), 52. Talayesva lived through the period in which the US government began its efforts to modernize and mainstream the Hopi, and his story is a fascinating one about the onset of hybridity.

[[2]]: For these metaphors, see Mary E. Black, “Maidens and Mothers: An Analysis of Hopi Corn Metaphors,” Ethnology vol. 23 no. 4 (October 1984), 279–288. See also John D. Loftin, Religion and Hopi Life in the Twentieth Century (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1991), 30 –31.

[[3]]: See Loftin, Religion and Hopi Life in the Twentieth Century, 4–5.A version of this myth is in Harold Courlander, The Fourth World of the Hopis (Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press, 1971). The Hopi emerged from underground via the sipapuni, into this fourth world.

[[4]]: See the essays by Ford and Ortiz in Corn and Culture in the Prehistoric New World, eds. Sissel Johannessen and Christine A. Hastorf (Boulder, Colorado, San Francisco, & Oxford: Westview Press, 1994).

[[5]]: Before the Spanish colonizing and introduction of livestock, meat was minimal, and hunting sometimes a ritual activity engaged in when the calendar precluded farming in the fall months.

[[6]]: Mischa Titiev, Old Oraibi: A Study of the Hopi Indians of the Third Mesa (Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press, 1992), 163, is probably the most famous exponent of this form of Enlightenment “explaining away” of Hopi religious practices. Fortunately, more recent scholars have a considerably more skeptical approach to such claims.

[[7]]: John D. Loftin, Religion and Hopi Life in the Twentieth Century, 14–15.

[[8]]: There are a few exceptions to this generalization concerning the Euro-American worldview, the cultural critic Wendell Berry being the most obvious.

[[9]]: See Mischa Titiev, Old Oraibi: A Study of the Hopi Indians of the Third Mesa, 184.This is a reprint of Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Anthropology and Ethnology, Harvard University, 1944, vol. 22, no. 1. See also Loftin, Religion and Hopi Life, 6–7.

[[10]]: Loftin, 7–8.

[[11]]: See Loftin, Religion and Hopi Life in the Twentieth Century, 7–12.

[[12]]: See Loftin, John D. Loftin, Religion and Hopi Life in the Twentieth Century, 71—83.

[[13]]: The Kachina and the White Man: The Influences of White Culture on the Kachina Cult (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, revised and enlarged edition, 1985), 148--149.

[[14]]: For example, in a telephone conversation in 2006, Emory Sekaquaptewa told me that the Hopi economy was still hybrid, a mix of subsistence and cash/commodity.

[[15]]: John D. Loftin, Religion and Hopi Life in the Twentieth Century (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1994), 88–89.

[[16]]: Richard O.Clemmer,Roads in the Sky:The Hopi Indians in a Century of Change (Boulder, San Francisco, and Oxford: Westview Press, 1995), 289.

[[17]]: Clemmer, Roads in the Sky, 275

[[18]]: For example, Frank Waters’ Book of the Hopi, 332, published in 1963. Waters states that “Even in New Oraibi [an alternate name for Kykotsmovi] there are no electric lights for homes.”

[[19]]: Armin Geertz in his The Invention of Prophecy: Continuity and Meaning in Hopi Indian Religion (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1994), 49, notes that the Hopi “image of reality sees humanity as an important and fateful element in the cycles of nature, where poor weather is equal to unethical and immoral behavior among humans. Personal and societal harmony are necessary ingredients in maintaining cosmic harmony and balance.”

[[20]]: Titiev, Old Oraibi, 178

[[21]]: Roads in the Sky, 306

[[22]]: Deliberate Acts: Changing Hopi Culture through the Oraibi Split (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1988)

[[23]]: Ann Douglas, The Feminization of American Culture (New York: Avon Books, 1977), 11-12

[[24]]: Lewis Hyde, The Gift: Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property (New York: Vintage Books, 1979), 139

[[25]]: Ibid. Related to this, it is interesting to note that Max Weber’s ideas on capitalism’s influence on religious belief fit into this paradigm, though Hyde sees the chicken as first, while Weber focuses upon the egg.

[[26]]: Ibid.

[[27]]: A Hopi friend whose livelihood is largely from pottery recently told me he was glad that he had not been able to finish a large and elaborate pot before a regional tribal arts show because one of his traditional responsibilities was to feed all the participants in the kachina dance for which he was officiant. In this vignette, we see the bifurcation his world into that of the worlds of Euro-American commerce and of tribal “gift” responsibilities

[[28]]: Kachina dances involve the kachinas giving gifts to the audience. But many of these gifts are now purchased rather than grown or made by their givers

[[29]]: Berry, Wendell, “Conserving Forest Communities” in Another Turn of the Crank (Washington DC: Counterpoint, 1995), 34

[[30]]: One of the most important differences that I do not have space to treat involves the place of prophecy in Hopi thought. According to both Loftin and Armin Geertz, the decay of Hopi religious tradition is itself foreseen in Hopi prophecy, which thus “contains” this decay within a traditional framework

[[31]]: I write “at least in the short term” because such voices as Wendell Berry’s and Philip Sherrard’s would all argue that social control and material control in their modern forms are a type of violence, and that some form of what is honestly “subsistence” agriculture grounded in a spiritual tradition is the only healthy basis for any continued human life on earth. Such pahanas or white men are “Hopi” in their outlook; and all of these thinkers would claim that our sense of control over nature is illusory, based upon an epistemological and existential shell game.