Central to my life has been a verse in the Holy Qur’an which addresses itself to the whole of humanity. It says: “Oh Mankind, fear your Lord, who created you of a single soul, and from it created its mate, and from the pair of them scattered abroad many men and women…” I know of no more beautiful expression about the unity of our human race, born indeed from a single soul.

— His Highness the Aga Khan[[1]]

Conflict and Fragmentation: The Spirit of the Age

We are living in an age characterized by conflict and fragmentation, where the spirit of the age is increasingly pitted against the Spirit itself. In W. B. Yeats’ prophetic words, things fall apart and the centre cannot hold. In the domain of religion, we have been witnessing conflicts often of political or economic origin though purporting to be based on religious differences – that feed reactionary claims. At the same time, we have been witnessing a secularist ascendancy that questions the legitimacy of religion as such as well as of specific religions. The modern world is placing its faith increasingly in science over religion, in earth over heaven, and in man over God – reductively preferencing polarity over complementarity. Not unrelated to this, there is a deepening ‘malaise of modernity’. Despite the scientific and technological advancements of our age, and its medical and material marvels, there is a strange and discomfiting sense of dislocation, disorientation, distraction, disconnection, disenchantment, and dispiritedness in our triumphal, if not hubristic, march of ‘progress.’ It is easy in such an age to be cynical or apathetic. Are we, in the biblical phrase, gaining the whole world but losing our own soul? Are we forgetting our very nature, and thereby our true place in the natural world? Are we losing our sense of the sacred, and thereby our integral relationship with the cosmos? In a sophisticated era where materialism seduces the soul with more immediate rewards than the promise of a deferred salvation, and where the zeal to indulge our individual freedoms and appetites is stronger than the restraint of responsibility and moderation, we are witnessing a centrifugal tug away from traditional notions of community and communion, and from our connection with the natural world. Uncertain of who we truly are, and lacking the awareness of our spiritual centre, it is easy for us to mistrust the ‘Other’ and to revert to tribal associations which particularly in a globalized world of porous boundaries and therefore of increasing diversity – can lead us to paths of conflict rather than of harmony.

There is a need for us to rediscover the integral foundations of life, of connection, of wholeness and equilibrium in our disjointed world. While these foundations may be rooted in religion, it is an especially difficult task, in an age where religion is in such disfavor, to address solutions in expressly religious terms. This is lamentable because religion as such is the expression, albeit in particular theological idioms, of the universal and perennial theme of Unity and of pathways to Union. And it is especially lamentable that Islam – a religion which preeminently signifies ‘peace’ in its very name – should be so misunderstood even as it is defamed by terrorist groups who, through barbaric acts, misrepresent their own avowed faith. There is a need, then, not only to rediscover the bond that connects us to each other, but also to provide a corrective to the misperceptions about Islam in a manner that is true to the essence of the Muslim faith, and to faith as such.

The Aga Khan and the Ismailis

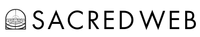

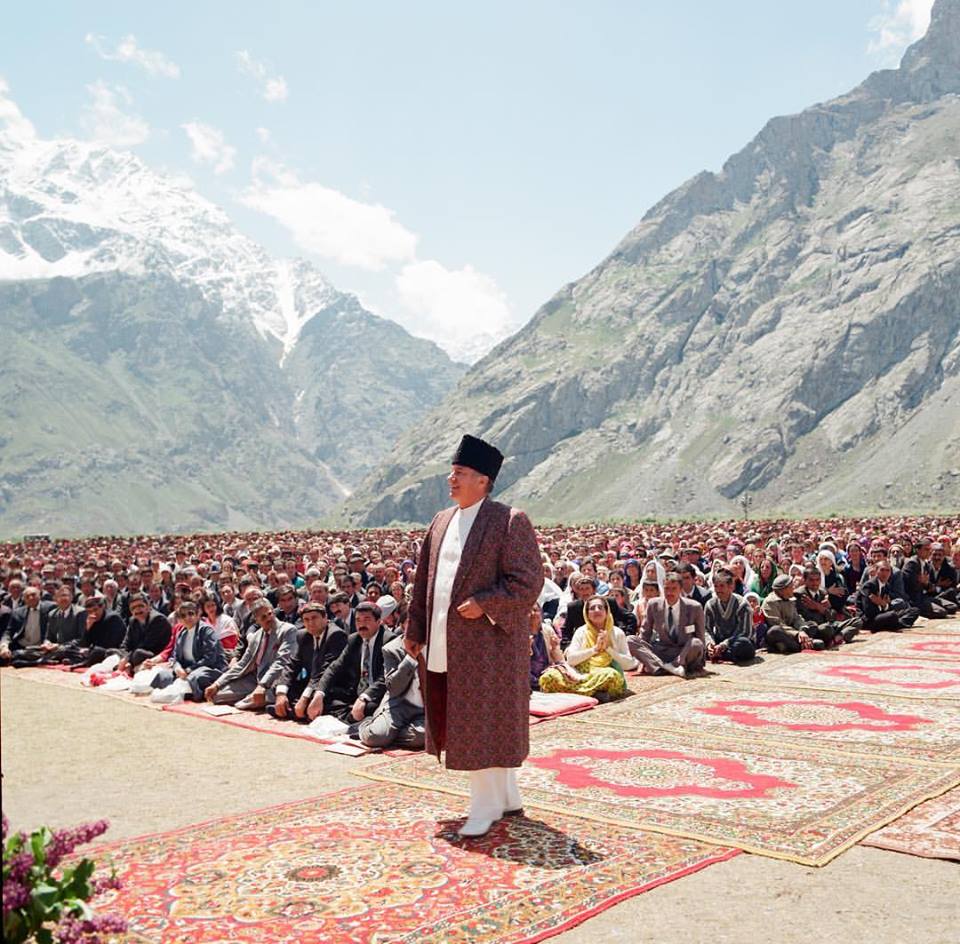

One quietly influential, moderate Muslim leader who has addressed the issue of the fragmentation of our times, and whose approach provides a corrective for Islam and for faith as such, is the spiritual leader of the Shia Imami Ismaili Muslim community – His Highness Prince Shah Karim Al-Husseini, known in the West by his title, ‘Aga Khan’. His approach, which can be summed up in the phrase ‘integral pluralism’, is true to universal and perennial principles that undergird his Muslim faith, while also appealing to secular humanists who might be wary of solutions couched in expressly religious terms.

By way of background, the Ismailis are a transnational community of Shia Muslims, located mostly in South and Central Asia, in parts of the Middle East and Africa, and in Canada, the USA, and Western Europe. The Aga Khan is the 49th ‘Imam’ or spiritual leader of his community, and is a direct descendant of Prophet Muhammad (p.b.u.h.), and the only living Shia Imam in a succession of Imams beginning with the Prophet’s cousin and son-law, ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib. The Ismaili ‘Imamat’ is a supra-national entity representing the succession of Imams through the Nizari Ismaili lineage, and has a legal status and function recognized under international law, notably by Portugal, where the Imamat established its Seat in 2015, and by Canada, where the Imamat established a formal ambassadorial presence, the Delegation of the Ismaili Imamat. The Ismailis’ heritage includes the glorious era of the Fatimid Caliphate in Egypt, where Ismaili Imams in the 10th century founded the city of Cairo as their capital and established Al-Azhar Masjid and University, one of the oldest surviving universities in history. From a theological perspective, the Ismailis follow spiritual principles emphasized by the Ja’fari jurisprudential school. As the Aga Khan noted in his letter to the Amman Conference in July 2005 [[2]],

Our historic adherence is to the Ja’fari Madhhab and other Madhahib of close affinity, and it continues, under the leadership of the hereditary Ismaili Imam of the time. This adherence is in harmony also with our acceptance of Sufi principles of personal search and balance between the zahir and the spirit or the intellect which the zahir signifies.[[3]]

As the Amman protocol indicates, the Ismaili approach is predicated on harmonizing the outer (zahiri) and inner (batini) realities through an intellectual and principial approach guided by the Ismaili Imam. This occurs through a reciprocal relationship whereby Ismailis pledge allegiance (bayah) to their Imam, who in turn guides them through the exercise of his ta’lim and ta’wil, that is, his intellectual-moral and principial-exegetical authority in conformity to spiritual principles (Usul ad-Din) and the traditions of Islam, adapted according to the needs of the changing times.

Underlying Principles

Central to these spiritual principles is the doctrine of unity (tawhid), which lies at the heart of Islam. It affirms that, though reality has multiple dimensions, it is essentially one. While discontinuous and transcendent, it is also continuous and immanent. Referring to the reality of One God, the Holy Qur’an states that “He is the First (al-Awwal) and the Last (al-Akhir), the Outward (az-Zahir) and the Inward (al-Batin)”[[4]] , affirming thereby that reality is absolute, with a phenomenal (zahiri) aspect as well as an esoteric (batini) dimension “which the zahir signifies”.

Implicit in this is the notion that Infinity (or multiplicity) is inherent in Absoluteness (or unity). Diversity can therefore be understood as an aspect of unity, or of inner and complementary harmony. The epistemological implication of this is that reductive reality – that is to say, opaque reality, perceived only in its outward aspect, not as transparent to transcendence – is based on an epistemic closure which veils theophany. Instead of seeing “the Face of God” everywhere[[5]], veiled humanity sees only the phenomenal world of multiplicity and outward difference. This kind of reductive perception is the very root of idolatry (shirk), which is forbidden in Islam because it opposes the basic creed of theophanic witnessing (shahada), of perceiving the reality that “There is no reality but God” (la ʾilaha ʾilla-Llah). Thus one can be veiled from reality by both the world and the egoic self, in each case through a fragmentary perception devoid of the sense of the sacred, and which thereby fails to perceive reality integrally, as holy, as whole. A further implication of the Absoluteness of reality is its Perfection. It is the Origin and Font of creation as well as its Perfection and End. Humanity shares both a common patrimony (being created “of a single soul”[[6]]) and a common matrix (being created and sustained by Divine Mercy[[7]]) so that outward difference can be transcended by radial reconnection to the same Centre in all things. Unique among all creatures, human beings are created with a divine nature (fitra) capable of the grace of self-knowledge and self-transcendence. Hence the hadiths, “Heaven and earth do not contain Me, but the heart of My faithful servant contains Me” and “Whoso knows himself, knows his Lord.” Humanity is made for Perfection. To this end, human beings are endowed with the freedom and fiduciary responsibility (amanah) to live in conformity with their divine norm. Thus the scripture asserts, “And so, set thy face steadfastly towards the [one ever-true] faith, turning away from all that is false, in accordance with the natural disposition (fitra) which God has instilled into man: [for,] not to allow any change to corrupt what God has thus created this is the [purpose of the one] ever-true faith; but most people know it not.”[[8]] In practical terms, these metaphysical principles of integral reality and human perfectibility have ethical implications. To conform oneself to integral reality requires one to live life with integrity. Despite their outward differences, human beings were created as separate communities so as to better know one another, to transcend their differences through the affirmation of their shared spiritual bond, and to vie with each other in good works.[[9]] Spiritual growth therefore balances spirit and matter and rejects the materialism and individualism that characterizes the ethos of modernism.

Critique of Modernism

The Aga Khan’s attitude to modernity is to embrace the modern world (for Islam is a faith for all time) while being critical of the modernist ethos which rejects the spiritual basis of life. Two examples from his speeches illustrate this. The first is from his address at the Seerat Conference in Pakistan in 1976, where he made the following observations about individualism and moral relativism:

I have observed in the Western world a deeply changing pattern of human relations. The anchors of moral behaviour appear to have dragged to such depths that they no longer hold firm the ship of life. What was once wrong is now simply unconventional, and for the sake of individual freedom must be tolerated. What is tolerated soon becomes accepted. Contrarily, what was once right is now viewed as outdated, old-fashioned and is often the target of ridicule.

In the face of this changing world, which was once a universe to us and is now no more than an overcrowded island, confronted with a fundamental challenge to our understanding of time, surrounded by a foreign fleet of cultural and ideological ships which have broken loose, I ask, “Do we have a clear, firm and precise understanding of what Muslim Society is to be in times to come?” And if as I believe, the answer is uncertain, where else can we search then in the Holy Qur’an, and in the example of Allah’s last and final Prophet?[[10]]

His Highness also cautioned in his Seerat Conference address that the modern world was increasingly at risk of losing sight of the Divine Countenance and of being trapped in “a shrinking cage” of materialism:

Thus it is my profound conviction that Islamic society in the years ahead will find that our traditional concept of time, a limitless mirror in which to reflect on the eternal, will become a shrinking cage, an invisible trap from which fewer and fewer will escape.[[11]]

The second illustration is from his address precisely three decades later at the Evora Conference in Portugal in 2006, where he asked,

How, in an increasingly cynical time, can we inspire people to a new set of aspirations – reaching beyond rampant materialism, the new relativism, selfserving individualism, and resurgent tribalism?[[12]]

The use of the expression “cynical time” reveals the His Highness’ concern about the loss of faith in modern materialistic and secularist societies. While not opposed to secularism as such, he has clarified that he is “opposed to unilateral secularism where the notions of faith and ethics just disappear from society.”[[13]] He has also expressed a concern about the deleterious effects of modern world’s secularist materialism and the potential for this to create divisions between the Islamic and Western worlds:

I fully understand the West’s historic commitment to separating the secular from the religious. But for many nonWesterners, including most Muslims, the realms of faith and of worldly affairs cannot be antithetical. If “modernism” lacks a spiritual dimension, it will look like materialism. And if the modernising influence of the West is insistently and exclusively a secularising influence, then much of the Islamic world will be somewhat distanced from it.[[14]]

While being a modern man, at ease in the West, he nonetheless rejects the Occidentalist view that the Muslim world should follow the path of the West in regard to its modernist excesses, and has stated,

Although the modern page of human history was written in the West, you should not expect or desire for that page to be photocopied by the Muslim world.[[15]]

Instead, His Highness has emphasized the importance of an ethos founded on perennial principles and values, true to his Muslim faith.

Faith and Ethics

Building on the Qur’anic foundations of unity and community, and recognizing the Muslim ethical tradition that links spirit and matter, the Aga Khan’s approach is premised on the convergence of faith and ethics. Rejecting the Augustinian division between faith and the world, he stresses that “Islam believes fundamentally that the spiritual and material worlds are inextricably connected”[[16]] and that Islam is not just a faith but a lived reality, an integral way of life. He has repeatedly spoken of ethics as a bridge between the realms of faith (din) and the world (duniya). In one of his key public addresses, he stated,

One of the central elements of the Islamic faith is the inseparable nature of faith and world. The two are so deeply intertwined that one cannot imagine their separation. They constitute a “Way of Life.”[[17]]

The “Way of Life” refers to the ethos of integral pluralism which lies at the heart of the Aga Khan’s interpretation of Islam. It is an ethic that requires human beings to live their lives integrally, transcending outward differences through dialogue and a respect for human dignity, according to the principles and values of their faith. This principial and practical approach, which transcends theological differences, is humanistic in its appeal. It has two main components: first, a cosmopolitan ethic that embraces diversity; and second, a social conscience that impels one to improve the quality of life for all. These elements are premised on a holistic view of life, on an inclusive vision of society based on its common humanity (born “of a single soul”), and on a recognition of the inherent dignity of humankind. With regard to the vision underlying his integral approach, the Aga Khan has noted,

Islam does not deal in dichotomies but in all-encompassing unity. Spirit and body are one, man and nature are one. What is more, man is answerable to God for what man has created.[[18]]

Human action must therefore be governed by the ethical imperative to respect the underlying unity of life and to sustain an equitable social order; in other words, to live according to “Islam’s precepts of one humanity, the dignity of man, and the nobility of joint striving in deeds of goodness.” [[19]]

These objectives are enshrined in the activities of the Imamat, conducted chiefly through the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), a network of agencies established by His Highness to improve the quality of human life in areas ranging from health, housing, economic welfare, and rural development to education and cultural pluralism. Speaking of the term “quality of life” and the purpose of AKDN, the Aga Khan has stated,

To the Imamat, the meaning of “quality of life” extends to the entire ethical and social context in which people live, and not only to their material well-being measured over generation after generation. Consequently, the Imamat’s is a holistic vision of development, as is prescribed by the faith of Islam. It is about investing in people, in their pluralism, in their intellectual pursuit, and search for new and useful knowledge, just as much as in material resources. But it is also about investing with a social conscience inspired by the ethics of Islam. It is work that benefits all, regardless of gender, ethnicity, religion, nationality or background. Does the Holy Qur’an not say in one of the most inspiring references to mankind, that Allah has created all mankind from one soul?

Today, this vision is implemented by institutions of the Aga Khan Development Network... The most important feature of these organisations… is that they share a vision, they work together, they create opportunity and they are inscribed in a single ethical framework.[[[20]]

This “single ethical framework” is a reflection both of the unitive holistic vision that is central to faith, and of the social conscience that is its ethical imperative. As His Highness has underlined, “Islam is a faith of tolerance, generosity and spirituality” [[21]] , and these three elements are interlinked. It is by virtue of our shared spiritual patrimony that tolerance and generosity are incumbent on us as human beings; tolerance being a reflection of spiritual integrity, and generosity an expression of social conscience. Thus, the Aga Khan has observed,

Faith should deepen our concern for improving the quality of human life in all of its dimensions. That is the overarching objective of the Aga Khan Development Network...[[22]]

Though the Aga Khan openly advocates Islamic principles as the basis of his Muslim faith, he prefers not to promote his public views in overtly religious language or to engage within the narrow dialectic of theological discourse. This is not because he regards religion as irrelevant. On the contrary, as he has stated, “The message I will always give is that humanity cannot deal with present day problems without a basis of religion.” [[23]] He is clearly aware that in an age where formal religion – and particularly Islam – is under attack and, some would even argue, in decline, there is a need for a broad-based appeal to universal and perennial principles and values. As the message of Islam is of universal appeal, and its principles and values of perennial import, they can be couched in a way that avoids the potential divisiveness inherent in the proselytism of theology.[[24]] His Highness’ preferred approach therefore is to speak in terms of a multifaceted humanism, of “universal human values which are broadly shared across divisions of class, race, language, faith and geography”[[25]] and which “constitute what classical philosophers, in the East and West alike, have described as human ‘virtue’ not merely the absence of negative restraints on individual freedom, but also a set of positive responsibilities, moral disciplines which prevent liberty from turning into license.”[[26]]

A Cosmopolitan Ethic

This is one of the reasons that the Aga Khan prefers to speak in terms of a “cosmopolitan ethic” as a central element of his integral pluralism. As he explains,

There are several forms of proselytism and, in several religions, proselytism is demanded. Therefore, it is necessary to develop the principle of a cosmopolitan ethic, which is not an ethic oriented by faith, or for a society. I speak of an ethic under which all people can live within a same society, and not of a society that reflects the ethic of solely one faith. I would call that ethic, quality of life.[[27]]

A fundamental attribute of the cosmopolitan ethic is “a readiness to accept the complexity of human society”.[[28]] Elaborating on this, and on the spiritual roots of tolerance, the Aga Khan has stated,

It is an ethic for all peoples. It will not surprise you to have me say that such an ethic can grow with enormous power out of the spiritual dimensions of our lives. In acknowledging the immensity of the Divine, we will also come to acknowledge our human limitations, the incomplete nature of human understanding.

In that light, the amazing diversity of creation itself can be seen as a great gift to us — not a cause for anxiety but a source of delight. Even the diversity of our religious interpretations can be greeted as something to share with one another — rather than something to fear. In this spirit of humility and hospitality, the stranger will be welcomed and respected, rather than subdued or ignored.

In the Holy Qur’an we read these words: "O mankind! Be careful of your duty to your Lord Who created you from a single soul … [and] joined your hearts in love, so that by His grace ye became brethren."

As we strive for this ideal, we will recognize that “the other” is both “present” and “different.” And we will be able to appreciate this presence — and this difference — as gifts that can enrich our lives.[[29]]

Globalization and Pluralism

One of the effects of modernity has been globalization, and with it has come the tension of living with “the other.” This tension can often result in conflict. The key to managing the tension is pluralism, which “means not only accepting, but embracing human difference.” [[30]] A strong proponent of pluralism, in 2006 the Aga Khan, in partnership with the Canadian government, established The Global Centre for Pluralism in Ottawa, Canada, as an independent, not-for-profit international research and education organization to cultivate the ethic of pluralism and to promote pluralistic goals worldwide.

His Highness views the need to combat the centrifugal influences of our time through the cultivation of a pluralistic ethic as one of the great challenges of the age. Thus, he has stated,

Diversification without disintegration, this is the greatest challenge of our time.[[31]]

This is a delicate task involving the balancing of identity and difference while avoiding the polarizations of homogenization and of tribalism. The former can result in a bland world of diluted identities, while the latter can result in ghettos and conflicts. This balancing task is vitally important because, as His Highness has noted, “every time pluralism fails, in one way or the other it ends up in conflict.”[[32]]

Yet, he laments that the modern world has not responded well to this challenge:

Sadly, the world is becoming more pluralist in fact, but not necessarily in spirit. “Cosmopolitan” social patterns have not yet been matched by “a cosmopolitan ethic.”[[33]]

The prevalence of greater diversity in modern societies can be perceived as a threat, as for instance in the case of the recent mass refugee migrations occurring from Syria and North Africa into Europe, prompting the Hungarian Prime Minister, Viktor Orbán to make a public plea in September 2015 “to keep Europe Christian.”[[34]] This tribalist tendency notion of a cosmopolitan ethic. In a public address at Harvard in November 2015, the Aga Khan explained,

A cosmopolitan society regards the distinctive threads of our particular identities as elements that bring beauty to the larger social fabric. A cosmopolitan ethic accepts our ultimate moral responsibility to the whole of humanity, rather than absolutising a presumably exceptional part. Perhaps it is a natural condition of an insecure human race to seek security in a sense of superiority. But in a world where cultures increasingly inter-penetrate one another, a more confident and a more generous outlook is needed. What this means, perhaps above all else, is a readiness to participate in a true dialogue with diversity, not only in our personal relationships, but in institutional and international relationships also.[[35]]

A ‘Clash of Ignorance’

Nowhere today is there a greater need for “a more generous outlook” and “a readiness to participate in a true dialogue with diversity” than in the case of relations between Islam and the West, which some have characterized as a ‘Clash of Civilizations’. His Highness is “vigorously opposed to any notion of intrinsic conflict between the Christian and Muslim worlds.” [[36]] Speaking of this so-called clash, he has commented,

The clash, if there is such a broad civilizational collision, is not of cultures but of ignorance.[[37]]

His Highness has cautioned that ‘ignorance gaps’ can easily become ‘empathy gaps’[[38]] and that what is required to bridge these gaps is a better cultural understanding and true cultural sensitivity. This “implies a readiness to study and to learn across cultural barriers, an ability to see others as they see themselves.”[[39]] He is as critical of Muslims in this regard as he is of the West, noting that “What we are now witnessing is a clash of ignorance, an ignorance that is mutual, longstanding, and to which the West and the Islamic world have been blind for decades at their great peril.”[[40]]

To provide a corrective in this regard, and to lead by example, His Highness has regularly spoken out about misperceptions in the Western world about Islam and Muslims, emphasizing the diversity and pluralism of Muslims and the tolerant spirit of their faith, while strongly condemning both the terrorist outrages that are wrongly attributed to the faith, and the misperceptions and stereotypes about Muslims, as well as the false assumptions about the causes of so-called ‘religious’ strife. And in promoting this corrective viewpoint, he has also frequently emphasized the vitally important role of educators, public figures, and a responsible media to promote cultural understanding and sensitivity. He has also undertaken major cultural initiatives worldwide, including restoring historical cultural sites and revitalizing Muslim traditions and societies[[41]], as well as establishing a major international museum[[42]] to highlight the pluralistic heritage of world civilizations, paricularly that of the Muslim world, and the multicultural symbiosis between them, and “to actively promote, internationally, the spirit of ‘convivencia’.”[[43]]

Social Justice

At the heart of the Aga Khan’s efforts is a quest to improve the quality of life of all human beings. This is in keeping with the Muslim ethos of promoting social justice, and it is impelled by the ethic of a social conscience that derives from humankind’s fiduciary obligation (amanah) to God. This is the primary objective of AKDN, a and fundamental recognition of the ethical foundations of society. Reflecting on this responsibility, the Aga Khan has stated,

There are those who enter the world in such poverty that they are deprived of both the means and the motivation to improve their lot. Unless these unfortunates can be touched with the spark which ignites the spirit of individual enterprise and determination, they will only sink back into renewed apathy, depredation and despair. It is for us who are more fortunate to provide that spark.[[44]]

The provision of that spark through the pursuit of social justice is linked to the human quest for social harmony and ethical living. The pursuit engages the ethic of social conscience, of generosity and service, of responsible stewardship, and of pluralistic dialogue and understanding. It reflects the humanistic ethic of interconnectedness grounded in humility and a profound respect for human dignity. These are all qualities that His Highness frequently emphasizes in his public speeches. From a practical perspective, the Aga Khan has also been a strong advocate for a culture of responsible government, based on merit and competence, and dedicated to improving the quality of life of all constituents. Noting the stresses within modern governments, he has commented that the choice between democratic government and competent government is a false choice, stating,

The best way to redeem the concept of democracy around the world is to improve the results it delivers. ... We must not force publics to choose between democratic government and competent government.[[45]]

In this regard, he has identified four elements that can strengthen democracy’s effectiveness: “improved constitutional understanding, independent and pluralistic media, the potential of civil society, and a genuine democratic ethic.”[[46]] The role of civil society (“an array of institutions which operate on a private, voluntary basis, but are motivated by high public purposes”[[47]]) is vital in this regard. It is an aspect of what His Highness has termed the ‘enabling environment’ that is necessary to promote social justice. Leading by example, the AKDN’s work in partnership with private groups, NGOs and government organizations, has engaged in a vast range of projects – from building hospitals, universities and educational academies worldwide, to assisting with strategies such as microfinance in rural areas, and to reviving cultures as “a trampoline for progress” – in order to improve the quality of peoples’ lives globally, not only in areas populated by Ismailis. And as Imam, the Aga Khan has emphasized to his followers the importance of serving one's fellow human beings, and of generosity, as an aspect of living the ethics of one's faith.

An Integral Vision

The approach of the Aga Khan as a Muslim leader of our times is a useful corrective to many of the misperceptions about Islam in today’s world. His words and actions illustrate not only the essentially peaceful message of the faith but also the perennial and universal relevance of its principles and values as exemplified in His Highness’ integral and pluralistic vision. It is a vision of a lived faith – of engagement with life through creating a bridge between faith and the world, a “bridge of hope” that places value in community while respecting individual aspirations, and that embraces diversity while remaining true to the principles of faith.

[[1]]: Address by His Highness the Aga Khan to both Houses of the Parliament of Canada in the House of Commons Chamber (Ottawa, Canada) 27 February 2014. The scriptural reference is to Surat an-Nisa, 4:1

[[2]]: All quotations from His Highness the Aga Khan are excerpted, with thanks, from the official Aga Khan Development Network website (http://www.akdn.org/speeches) and, on occasion, from the online archive known as NanoWisdoms (http://www.nanowisdoms.org/nwblog). Some of the speeches cited in this article are also excerpted from the publication Where Hope Takes Root: Democracy and Pluralism in an Interdependent World by His Highness the Aga Khan, introduction by the Rt. Hon. Adrienne Clarkson, © 2008 by Aga Khan Foundation Canada, published by Douglas & McIntyre Ltd. (hereafter cited as Where Hope Takes Root)

[[3]]: Amman Message, July 2005. The Amman Message is an initiative of the Royal Court of Jordan, begun in November 2004. It sought to define the Ummah (or Muslim community) and thereby to portray its diversity – an important retort to those who might seek to portray it as homogeneous. The Ismailis were recognized in the Amman Message as a part of the Ummah through a protocol from which the excerpt herein is cited. See https://ammanmessage.com

[[4]]: Surat al-Hadid, 57:3

[[5]]: Surat al-Baqarah, 2:115 (“Unto God belongs the East and the West, and wherever you turn, there is the Face of God. Truly, God is All-Embracing, All-Knowing.”)

[[6]]: Surat an-Nisa, 4:1

[[7]]: God is referred to in the Holy Qur’an as both Rahman (intrinsic Mercy, the divine quiddity that is the “Hidden Treasure” of the Hadith of the Hidden Treasure, which describes creation to be an act of Divine Self-manifestation that projects the qualities of the divine treasury into existential reality as an aspect of His intrinsic goodness) and Rahim (extrinsic Mercy, the womb-like matrix that umbilically sustains and integrates creation)

[[8]]: Ayat ar-Rum, 30:30

[[9]]: Surat al-Maidah, 5:48: “For each We have appointed a divine law and a traced-out way. Had God willed He could have made you one community. But that He may try you by that which He has given you (He has made you as you are). So vie one with another in good works. Unto God you will all return, and He will then inform you of that wherein you differ.”

[[10]]: Presidential Address, International Seerat Conference, ‘Life of the Prophet’ (Karachi, Pakistan), 12 March 1976

[[11]]: Ibid

[[12]]: Remarks by His Highness the Aga Khan at Evora University Symposium: “Cosmopolitan Society, Human Safety and Rights in Plural and Peaceful Societies” (Evora, Portugal), 12 February 2006

[[13]]: Spiegel Online Interview, Stefan Aust and Erich Follath, ‘Islam Is a Faith of Reason’ (Berlin, Germany), 12 October 2006

[[14]]: School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University, Commencement Ceremony (New York, USA), 15 May 2006

[[15]]: Baccalaureate address at Brown University on 26 May 1996

[[16]]: Address by His Highness the Aga Khan to both Houses of the Parliament of Canada in the House of Commons Chamber (Ottawa, Canada) 27 February 2014

[[17]]: From “The Spiritual Roots of Tolerance”, speech made at the Tutzing Evangelical Academy, upon receiving the Tolerance Prize, 20 May 2006; Where Hope Takes Root, p.124, at p.125

[[18]]: Remarks by His Highness the Aga Khan at the inauguration of the Ismaili Jamatkhana and Center, Houston, Texas (USA), 23 June 2002

[[19]]: The Delegation of the Ismaili Imamat Foundation Stone Ceremony (Ottawa, Canada) 6 June 2005

[[20]]: Alltex EPZ Limited Opening Ceremony (Athi River, Kenya), 19 December 2003

[[21]]: Golden Jubilee Inaugural Ceremony (Aiglemont, France) 11 July 2007

[[22]]: 88th Stephen A. Ogden, Jr. Memorial Lecture on International Affairs, Brown University (Providence, USA) 10 March 2014

[[23]]: Press Conference, Kampala, 18 September 1959

[[24]]: This is evident from the following comments relating to his views on inter-faith dialogue: “In recent decades, inter-faith dialogue has been occurring in numerous countries. Unfortunately, every time the word ‘faith’ is used in such a context, there is an inherent supposition that lurking at the side is the issue of proselytisation. But faith, after all, is only one aspect of human society. Therefore, we must approach this issue today within the dimension of civilisations learning about each other, and speaking to each other, and not exclusively through the more narrow focus of inter-faith dialectic.” – Keynote Address to the Annual Conference of German Ambassadors (Berlin, Germany), 6 September 2004

[[25]]: School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University, Commencement Ceremony (New York, USA), 15 May 2006

[[26]]: Ibid

[[27]]: Paroquias de Portugal Interview, António Marujo and Faranaz Keshavjee, (Lisbon, Portugal), 23 July 2008

[[28]]: 10th Annual LaFontaine-Baldwin Lecture, Institute for Canadian Citizenship, ‘Pluralism’, (Toronto, Canada) 15 October 2010

[[29]]: Ibid

[[30]]: “How the world is shaped by the ‘Clash of Ignorances’” – published in the Daily Nation (Nairobi, Kenya) 15 June 2009

[[31]]: 88th Stephen A. Ogden, Jr. Memorial Lecture on International Affairs, Brown University (Providence, USA) 10 March 2014

[[32]]: CBC Interview, ‘One-on-One’ with Peter Mansbridge (Toronto, Canada) 1 March 2014

[[33]]: Address to both Houses of the Parliament of Canada in the House of Commons Chamber (Ottawa, Canada) 27 February 2014

[[34]]: Prime Minister Orbán’s statement was published in September 2015 in the German newspaper, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. It stated, “Let us not forget, however, that those arriving have been raised in another religion, and represent a radically different culture. Most of them are not Christians, but Muslims. This is an important question, because Europe and European identity is rooted in Christianity. Is it not worrying in itself that European Christianity is now barely able to keep Europe Christian? If we lose sight of this, the idea of Europe could become a minority interest in its own continent.”

[[35]]: Samuel L. & Elizabeth Jodidi Lecture, Harvard University (Cambridge, USA) 12 November 2015

[[36]]: La Croix Interview, Pierre Cochez and Jean-Christophe Ploquin (Paris, France), 8 April 2003

[[37]]: Keynote Address to the Governor General’s 2004 Canadian Leadership Conference: ‘Leadership and Diversity’ (Gatineau, Canada), May 19, 2004

[[38]]: 88th Stephen A. Ogden, Jr. Memorial Lecture on International Affairs, Brown University (Providence, USA) 10 March 2014. Also, Keynote Address, Athens Democracy Forum (Athens, Greece) 15 September 2015

[[39]]: The Peterson Lecture, Annual Meeting of the International Baccalaureate (Atlanta, USA) 18 April 2008

[[40]]: Banquet hosted in Honour of Governor Perry (Houston, Texas, USA), June 23 2002

[[41]]: Through the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, it has engaged in several restoration projects as part of its Historic Cities Program, among which, notably, have been the Al Azhar Park project in Egypt, Humayun’s Tomb in India, the Citadel of Aleppo in Syria, the Baltit Fort in Pakistan, the Old Cities in Kabul and Herat, Stone Town in Zanzibar, and the Great Mosque of Mopti in Mali

[[42]]: The Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, Canada, which opened in September 2014

[[43]]: Introduction to ‘The Worlds of Islam in the collection of the Aga Khan Museum’ (Madrid and Barcelona, Spain) 5 June 2009

[[44]]: Quoted in CBC Interview, ‘Man Alive’ with Roy Bonisteel (Canada), 8 October 1986, from a speech made in India on 19 January 1983

[[45]]: School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University, Commencement Ceremony (New York, USA), 15 May 2006

[[46]]: Keynote Address, Athens Democracy Forum (Athens, Greece) 15 September 2015

[[47]]: Address to both Houses of the Parliament of Canada in the House of Commons Chamber (Ottawa, Canada) 27 February 2014