In the Name of God, The Most Merciful, The Most Compassionate

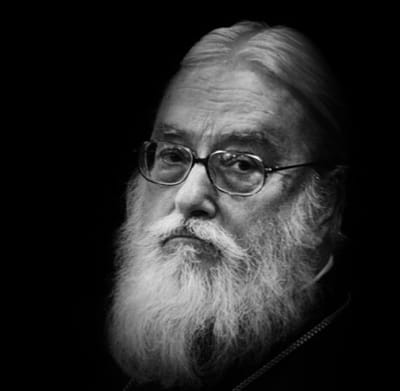

I am grateful to be given this opportunity to write a few words about reminiscences concerning His Highness Prince Karim Aga Khan on the occasion of his Diamond Jubilee.

I have known him personally for over six decades and have met him in places as far apart as Cambridge, Massachusetts, in the USA, Aiglemont, Gouvieux, in France, and Tehran in my home country of Iran. The trajectory of the meeting of the lines of his noble family and mine goes back to even before Prince Karim and I met in the mid-1950s at Harvard. When Pakistan became independent, my uncle, Seyyed Ali Nasr, became Iran’s first ambassador to the newly founded nation and soon became close friends with His Highness Sir Sultan Mohamed Shah, Aga Khan III, Prince Karim’s grandfather, to the extent that later when Sir Sultan Mohamed Shah and the Begum would come to Iran, they would visit the Nasr family home in Tehran.

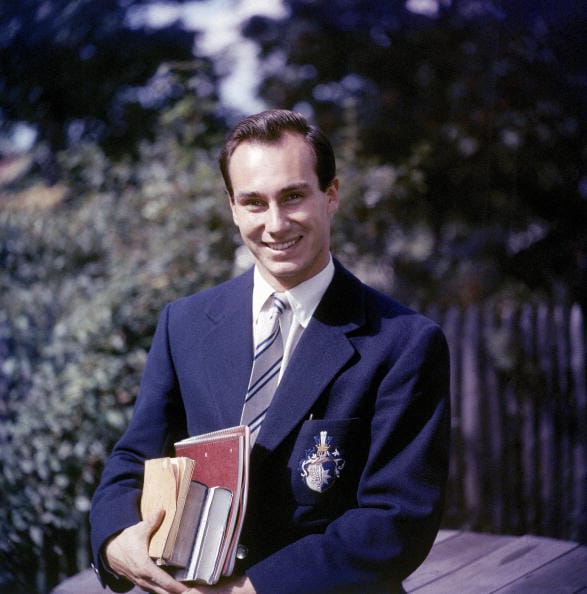

When I went to Harvard in 1954, I founded the Harvard Islamic Society, the first Islamic Society to be established in an American University. Among its seven original members was the late Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan, Prince Karim’s uncle with whom I became good friends. Shortly thereafter, when as a teaching fellow at Harvard I was giving a lecture on Islam, I met the young Prince Karim who was then a student in my class. We became close friends and he would occasionally even visit our home where my mother, who was then residing in the Boston area, would cook Persian food for him which he appreciated like most other things Persian.

It was in this period that during a university holiday he was called away to Europe to visit his grandfather, Sir Sultan Mohamed Shah, during his last illness, and on his passing on July 11, 1957, Prince Karim was, according to the hereditary customs of the Shi’a Imami Ismaili Muslims, appointed by the Last Will of the late Imam to succeed to the title of ‘Aga Khan’ and to be Imam and Pir of his community. He was 20 at the time. When the young Prince Karim, now Imam and Aga Khan IV, returned to Cambridge, we continued our discussions but on a deeper level about Islam, its art and philosophy, Twelver Shi‘ism and its relation to Ismailism and the whole question of imāmah or the Imamat in addition to many other related subjects. I would often speak to him about the fact that Ismailism was and remains a part of the totality of Shi‘ism and therefore of Islam, and I was very glad to see that soon he added the name Shi‘a to the official name of the branch of Ismailism of which he was now the ḥāḍir Imam.

When I returned to Iran in 1958 my relation with His Highness continued. He wanted to have a new generation of Ismaili intellectual leaders trained and, to that end, he sent several very gifted Ismaili students to Tehran University where I was teaching and they completed their doctorate under my care. His keen interest in the Islamic intellectual tradition combined with devotion to Islamic art and architecture was and is unique among major Islamic leaders.

The early Sixties were the hey-day of Arab nationalism, both Nasserism and the Ba‘th movement, the latter led ideologically by Christian Arabs such as Michel Aflaq and Constantine Zurayk, who was a professor at the American University of Beirut (AUB), which was then the intellectual seat of Arab nationalism. It was at the AUB that such famous Jordanian and Palestinian nationalists as Nayef Hawatemah and Yasser Arafat as well as many Lebanese and Syrian political figures had studied, and where there was the attempt both to secularize Islam or to reduce it to a part of Arab nationalism. His Highness Prince Karim decided very wisely that it was there, precisely because of the AUB’s influential position, that he would seek to establish a Chair of Islamic Studies, and he indicated that he wanted me to apply for it and to go to the AUB in Beirut to found the Chair. At the time, I was very busy in Iran and did not want to leave my country for a whole year, but I obliged to follow His Highness’s suggestion and when the invitation came from AUB to apply for the Aga Khan Chair, I sent them my CV and publications, and soon afterwards I was informed that I had been chosen for the Chair. And so, I spent the whole academic year of 1964 – 1965 in Beirut as Aga Khan Professor, a year that was one of the most difficult and at the same time most fruitful of my life.

The opposition among many members of the faculty to Islam being taught by a Persian who was at the same time a Shi‘ite was more than I had imagined. It had been easier for me to teach Islamic subjects from a Muslim point of view at Harvard where I had been visiting professor just two years earlier than to teach such subjects in Beirut. But I had the full backing of His Highness and that support gave me strength in carrying out his wishes to sink the roots of Islamic studies in the soil of the intellectual heart of modern Arab nationalism and modernism.

His Highness the Aga Khan wanted me to give a long series of public lectures on Islam, its culture and civilization in addition to teaching courses on them. The faculty members of the History Department where the Aga Khan Chair was located were opposed to the public lectures on the pretext that there would be no audience for them. But I insisted on delivering the lectures because it was the wish of His Highness. The faculty members finally relented but refused to help in any way. With the assistance of the late Yusuf Ibish, then professor at AUB, who was a close friend of mine and who had known the young Prince Karim at Harvard when Ibish was working for his doctorate, we put up some posters in Ibish’s fine handwriting in various places on the campus, including on some trees, and arranged for a hall for the series, which I named “Dimensions of Islam.” Several hundred people came to the first lecture and more to the next and this trend continued until the university authorities were finally forced to hold the lectures in the large church of AUB, a place built originally to spread Christianity among Muslims. Every week the famous Arab scholar Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn al-Munajjid would write an Arabic summary of my lectures of that week in a leading Lebanese newspaper and soon the name of the Aga Khan Chair became known among scholars in much of the Arab world.

His Highness also wanted me to prepare the formal written version of these lectures and publish them as a book. To that end, while still in Beirut, I prepared the text of the first six lectures which came out later in London as Ideals and Realities of Islam, a book that is still in print and being taught to this day over a half century since its original publication. The book, which has also been translated into numerous Islamic and European languages, and which owes its existence to His Highness, made the name of the Aga Khan Chair renowned in various parts of the Islamic world, even beyond the Arab countries, as well as in the West.

An episode occurred that is worth mentioning here to bring out another aspect of His Highness beyond his love for knowledge and art. Once, when he was visiting Iran and was staying at the royal suite in the Hilton Hotel that was close to my house, he called me and asked me to go to the hotel to meet him, which I did. It was the evening and as I was standing in the lobby waiting for him, the door of the elevator opened up and His Highness came out of the hotel to be driven to the Royal Palace to dine with the Shah of Iran. Prince Karim embraced me warmly and, while we were speaking together, a group of some thirty or forty people, whom one could detect were from the provinces and simple people, probably mostly peasants, rushed into the lobby and with extreme devotion tried to come near His Highness to bow before him and to touch him, but his guards prevented them from coming too close. They were in a state of both pious devotion and ecstasy. Anyway, I walked with His Highness to the car that the Shah had sent for him and he soon departed. Immediately after he left, the crowd rushed towards me, touching my clothing, then putting their hands on their hearts or over their eyes. I asked what they were doing. One of them said that they were Ismailis from Maḥallāt, the town from which the family of the Aga Khan had hailed, and he explained that since the Aga Khan had embraced me and kissed my cheeks, I had received his barakah which they wanted to share.

This experience points to a spiritual reality beyond the reality of words and ideas coming from the Ismaili Imam concerning the truth and being received by those around him; it had to do with his spiritual presence and its transmission. Every integral religion possesses the dimensions of both truth and presence and the ḥāḍir Imam of the Ismailis could certainly not be devoid of these dimensions, but for me it was the first time that I had experienced not just his intellectual knowledge, thoughts or sentiments, but the dimension of spiritual presence of the Aga Khan as Imam that was felt so vividly by his ordinary followers. It is this presence that makes what Ismailis call dīdār of the Imam so precious for them.

The activities of the Aga Khan during his long Imamat have been remarkably diverse and influential, particularly through the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN) agencies of the Imamat which focus on improving the quality of human lives. Historically speaking, we would have to go back to the Fāṭimid period to find an Ismaili Imam to compare with him in both the breadth and depth of his achievements. His vast number of speeches range from practical matters of education and economic activity, to pluralism and the cosmopolitan ethic, and to the philosophical issue of the contraction of time as a result of the advent of modernism. The scholarly and well-written work of M. Ali Lakhani, Faith and Ethics: The Vision of the Ismaili Imamat (IB Tauris/IIS, 2018), makes clear the vast scope of the Aga Khan’s actions and thoughts to which I cannot do justice in this short essay. Here, I wish only to underline a few of his accomplishments with which I am more familiar.

The first one that I believe to be very important to mention is that, although naturally the Aga Khan speaks sometimes specifically to his Ismaili community as their Imam, he speaks usually to his audiences as a Muslim even when addressing global issues. He is not only the Ismaili Imam, but also a major figure, both intellectually and spiritually, in the Islamic world. In contrast to the Imam of the other branch of Ismailism, the Bohras, whose fame and influence are confined mostly to the Subcontinent of India where most of his followers reside, the Aga Khan is known throughout the Islamic world as not only the Ismaili Imam, but also as a major Muslim figure. The same can be said for his stature in the world at large. His cultural, intellectual and philanthropic activities have never been confined and limited by sectarian considerations or geographical and ethnic ones.

Then there is the whole field of education. His activities in this domain have ranged from building schools for the young in East Africa to establishing the Aga Khan University in Pakistan and the University of Central Asia whose campuses are located in various Central Asian countries, which are both open to students of different faith backgrounds. Prince Karim has been especially concerned with, and has felt responsible for, Ismaili education and the goal of reviving the Ismaili intellectual tradition. Why is it that Ismailism, which was so active in the early period of Islamic philosophy, did not produce a Ḥamīd al-Dīn Kirmānī or a Nāṣir-i Khusraw in later centuries? If the Sunni Arab world also did not in later centuries produce figures such as al-Kindī, Ibn Rushd or Ibn Khaldūn, the reason has been the dominance of Ash‘arism, combined with certain other factors which did not exist in the Sunni Turkish world and Muslim India where the Islamic intellectual and philosophical tradition continued to flourish, not to speak of Persia, the main area of later Islamic philosophy where Ash‘arism was rejected. But why did Ismailism, like Twelver Shi‘ism also reject Ash‘arism? I am certain that this question has been on His Highness’s mind as he has sought to bring Nizari Ismailism closer to its Shi‘ite roots. If another Nāṣir-i Khusraw appears upon the scene, it will be due to a large extent to the Aga Khan’s foresight and activities.

The Aga Khan’s vision to revive Islamic thought and scholarship can also be seen in the establishment of The Institute of Ismaili Studies of London which has already produced a number of important works on Islamic thought in general as well as on Ismailism in particular. The Aga Khan’s non-sectarian vision is evidenced by the fact that in this Institute there are not only scholars of Ismailism associated with it, such as its past and present directors, Azim Nanji and Farhad Daftary, but also non-Ismaili and even non-Muslim scholars such as Wilfred Madelung, a famous German scholar who had previously been at Oxford, and younger scholars such as Toby Mayer and Reza Shah-Kazemi. This unique institution owes its existence and philosophy to the vision of His Highness.

Located at the heart of the Knowledge District in London's King's Cross, the Aga Khan Centre is home to the Institute of Ismaili Studies and features 7 Islamic-inspired gardens. The Garden of Light, pictured above, draws inspiration from the gardens of Andalusia and includes engraved verses of poetry by Nasir Khusraw. Source: TheIsmaili

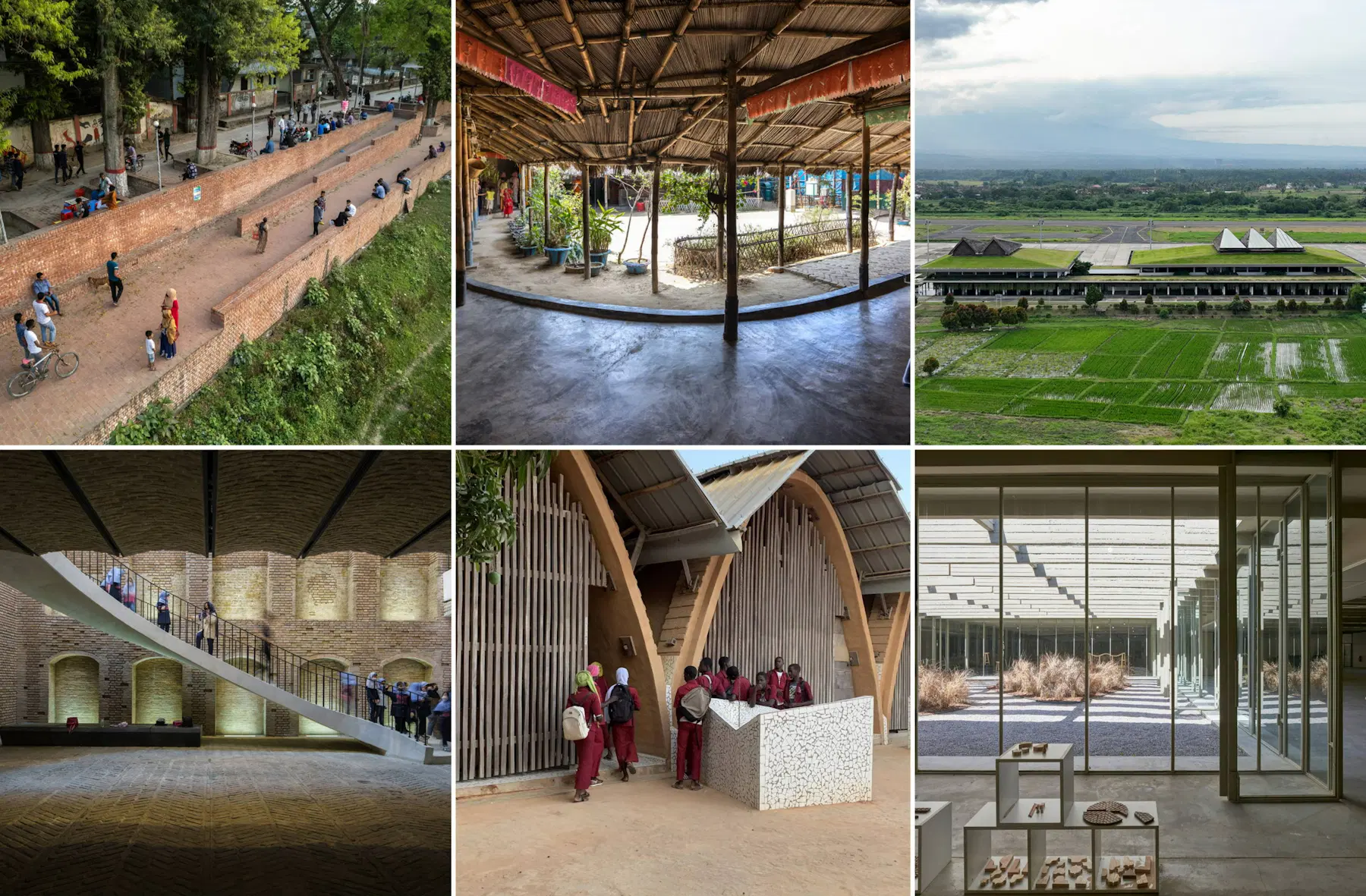

Finally, in this short treatment I must mention again one of the central and abiding concerns of the Aga Khan, which is Islamic art and architecture. Now that King Hasan of Morocco and the former Empress of Iran, Shahbanou Farah, are no longer on the scene, the Aga Khan remains the only major Muslim leader who is deeply devoted to the repair, maintenance, revival, and re-flourishing of Islamic architecture. To this end he established the Aga Khan Award for Architecture and the Aga Khan program in Islamic architecture at Harvard and MIT. The two initiatives of His Highness have helped greatly to increase the consciousness of Islamic architecture in the West and even in the Islamic world itself. The Aga Khan’s activities in this domain will surely remain one of his most significant legacies.

I can conclude only by praying for the well-being of Prince Karim Aga Khan. May God give him many more years to serve and be a guiding light not only for his own Ismaili community, and not only for dār al-islām, but also for the world at large where there is so much need today for leaders with his knowledge, insight and vision.