“There is a polish for everything that taketh away rust; and the polish for the heart is the remembrance of God.”

Hadith of the Holy Prophet of Islam

We live in a world of distraction—which is to say that we are distracted from the Absolute by the world of contingency, and from the Centre by the periphery. We have forgotten who we truly are, and why we are here. We can no longer locate our true origin, and we identify physical death as our only end. We are fleeing from ourselves into a world of impermanence, and in the flux that subsists, there is no abiding Presence. Those who are blinded by this distracted world see only a soulless universe of disparate elements that some claim to have emerged out of material forces according to laws that modern science alone can divine—soulless laws offering no comfort to those who seek a deeper meaning of existence. In such a bleak world, our earth is no more than a speck in the cosmic dust and man is no more than a machine, one that is now in danger of being eclipsed by the monsters of his own creation.

There is, however, an alternative view of reality, based upon a spiritual foundation common to all faith traditions. It is verifiable by our innate intelligence and by the soul’s participatory awareness of its spiritual amplitude—its awareness of the deep interconnectedness of life. The foundation of this worldview is the Absolute Reality whom theistic faith traditions refer to as “God”, and non‐theistic traditions as “the Principle” or “Being”. This Reality is the Presence who inhabits us as “the centre of our sinful earth” (Shakespeare, Sonnet 146) and in whom “we live and move and have our being” (Acts, 17:28). It is our Origin and our End, from whom we have come and to whom we will return, and to whom we will be accountable as to whether we have lived our lives with spiritual integrity, true to our spiritual nature and its ethical obligations.

These two worldviews contend within the soul of man in a battle of dust and spirit, the two elements from which Adam was created, in a contest of remembrance and forgetfulness, a contest between our faith in ‘permanent things’ and our attachment to the fleetingness of the evanescent world. Throughout this contest, God is ever‐present. It is we alone who, given the choice to remember or to ignore Him, absent ourselves from remembrance through the distractions of the world.

Prayer is the ladder that connects man to God. To ascend its rungs is “the one thing needful” (Luke 10:42) for prayer offers a protective polish against the rust of the corrosive world (the rust upon the hearts of forgetful men, as the Qur’an warns [Surat Al-Mutaffifin 83:14]). Prayer is the remembrance of God. It is the awareness of the Sun amid a world of shadows. It is the recognition that God is present in all things, yet transcends them. It is our awareness of the theophany, our witnessing of its signs within and around us, and of the inner reality that each creature knows “its own mode of prayer and praise” [Surat An-Nur, 24:41].

Despite its importance, there is a tendency to neglect prayer in an increasingly irreligious world, or to privatize it in an increasingly secularized world, or to reduce it to its outward ritual elements in the context of formalized religion. While there is clearly a role for different aspects of prayer (such as canonical, confessional, contemplative or invocatory) in both the public and private domains, it must be recalled that the essential purpose of prayer is transformative—to connect man to God. For this reason, transformative prayer can be said to be continuous and therefore it cannot be compartmentalized in any reductive sense. It reflects and reminds us of the spiritual substance in our own being and in all things. It is therefore a way of deepening our self‐knowledge and our knowledge of the world. Through the grace of this knowledge, it possesses an operative dimension which we carry with us into the world. As we change our perceptions of who we are and what the world is, seeing how interdependent we are with our fellow‐creatures and how interconnected our faith is with life, this recognition expresses itself in an ethic of compassion that is a natural corollary of prayer. Through prayer, we carry God within our being into the world.

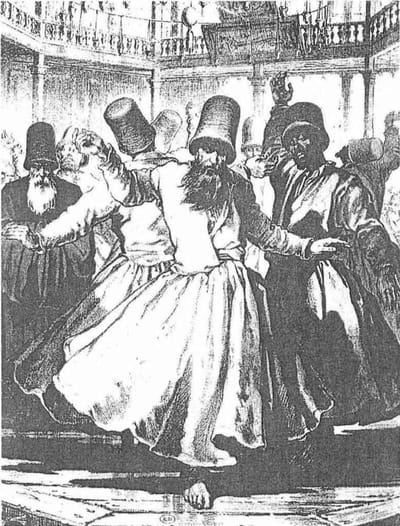

One of the terms for prayer in Islam is dhikr, which means both ‘remembrance’ and ‘invocation’. Through prayer, we are, as it were, ‘re‐ membered’ (or transformed) by what we invoke. In a scriptural verse, God says, “Remember Me, and I will remember you.” [Surat Al-Baqarah 2:152] One way of understanding the ‘promise’ by God to remember the one who remembers Him is to see in it the operative reality of the transformative awareness of God. Truth is Presence: we are realized by the Reality we invoke. Through the remembrance of God, He is invoked in our own lives, not only as Present in the hidden depths of our being, but also outwardly in the words and actions we express in conformity with our realized nature. In this oneness of being, there is an identity between the Invoker, the Invoked, and the Invocation.

To pray is to give ourselves up to God. But as we pray, God gives Himself up to us in an act of grace. This is expressed in a beautiful Hadith in Islam, in which God utters these words which illustrate the scriptural promise of the transformative effect of dhikr:

My faithful servant approaches Me with nothing more beloved to Me than what I have made obligatory upon him, and keeps drawing nearer to Me with voluntary works until I love him.And then, when I love him, I am the hearing with which he hears, the sight with which he sees, the hands with which he works, and the feet by which he walks.

It is in this sense that“prayer fashions man”—emptying man of himself so that he can be filled with the reality of the invocatory Presence. We end with the words of Frithjof Schuon:

Man prays, and prayer fashions man. The saint himself has become prayer, the meeting place of earth and Heaven; he thus contains the universe, and the universe prays with him. He is everywhere where nature prays, and he prays with and in her; in the peaks that touch the void and eternity, in a flower that scatters its petals, or in the lost song of a bird. Whosoever lives in prayer has not lived in vain.