Now the world is totally transfigured into God; its totality rests within the inner realm of God’s totality, its unity encounters the primordial unity. The radiance of God’s glory streams over it, as the splendor of the sun overpowers the light of the stars

- St Maximus

The quotation[[1]] is from a book about one of the greatest Christian saints and teachers of the monastic tradition, Maximus the Confessor or Maximus the Theologian (580-662). The book is by one of the greatest modern Christian theologians, Hans Urs von Balthasar, whose work did a great deal to bring Maximus back to the attention of Christian theologians in the twentieth century. It gives us a taste of orthodox Christian mysticism, to which we will return at the end.

Unity of Being

But I want to talk first about Muhyiddin Ibn ‘Arabi (1165-1240), known to many Sufis as “the Greatest Shaykh.” In an introduction to his life and thought[[2]], Stephen Hirtenstein writes about the mystical Jewish, Christian, and Muslim tradition of which Ibn ‘Arabi was perhaps the supreme exponent: “In this tradition, God is not understood to be a Being, or even the Supreme Being above and beyond the universe, for both conceptions imply that there are other beings outside Him. What is meant by God is simply Being as such. This cannot ever become an object of knowledge or contemplation or thought; it can only be known as unknowable, but simultaneously it presents itself as both knower and known, contemplator and contemplated, lover and beloved.”

This seems to go to the heart of things: Ibn ‘Arabi’s doctrine of “Wahdat al-Wujūd,” or the Unity of Being. It appears at times to resemble a kind of pantheism, but it is no more pantheistic than the writings of St Thomas Aquinas, or so I wish to demonstrate. I am no student of Arabic, let alone of Ibn ‘Arabi, but the Ibn ‘Arabi Society has an archive of excellent scholarly articles on its website, and so I am able to quote Souad Hakim’s paper on the topic of the “Unity of Being”, where she writes as follows:

“The expression ‘He is He’ (Huwa Huwa) is widely used to denote the Unity of Being. It means that God and the creatures have a single essence, and such an expression is not in agreement with the Unity of Being in Ibn ‘Arabī. It is for that reason that we have coined a new expression ‘He Within Himself ’ (Huwa fî Huwa). This expression respects the Lord- Servant duality, and translates the manifestation of God in every instant (mawjūd), not in Himself but through His Most Beautiful Names. We may here quote a text of Ibn ‘Arabī which describes the manifestation of God in created things, in accordance with the expression ‘He Within Himself ’ (Huwa fî Huwa), ‘God is too Exalted and High to be known as He is In Himself (fî nafsihi). Yet He is known in created things [...] Some see God in things while others see things and God in them.’”[[3]]

Yet, as she also says, “There is no Being other than God’s, and the whole universe is the effect of the manifestation of His Names. If the perpetual theophany were to stop for the blinking of an eye, the whole universe would fall into non-being.” Is this really compatible with Christianity? Well, it is certainly compatible with a certain reading of St Thomas Aquinas, the most respected Christian philosopher and theologian of all time, born when Ibn ‘Arabi was about 60 years old. For Aquinas, there is no question but that the world exists, and it is not God. At the same time, only God has Being, and all else has something merely analogous to being—a kind of reflective participation, if you like. Compared to God’s being, ours is non-existence.[[4]]

Divine Knowledge

What is a thing, from Aquinas’s point of view? First, some vocabu- lary is needed. The Latin word for “thing” is ens. It is derived from the verb esse, which means the act of being or existing. So a thing, or ens, is a being that exists. Essence or essentia, on the other hand, is what that something is (“quiddity”). We can make this easier by using the English words “is” and “what” to help us along. The “is-ness” of something is its existence, its being (esse, wujūd). The “what-ness” of something is its essence. Everything in the world has both isness and whatness. In other words it is, and it is something in particular. I can ask “what is it?” and get an answer. It is this, not that.

But with God things are different. What makes God different from everything that exists, understood in terms of the philosophical tradition that unites both Ibn ‘Arabi and Aquinas,[[5]] is that God is his isness. He has no whatness that would be really distinct from his isness. Or rather, if you ask “what is he?” you receive the answer, “He is.” His whatness (essence) is his isness. He is the pure act of existing. Everything else depends on him, is caused by him, or participates in his act of being. That is the philosophical way of saying that things are created by him. And God confirmed this view of himself to Moses when he appeared in the burning bush and said, “Tell the Israelites that I AM sent me to you.” God is I AM, the pure act of being, “He who is” (Ex. 3:14). Nothing else, because, in a sense, there is nothing else—except reflections and images or shadows of that one act.

Aquinas asks what God knows, and specifically how he knows the things he has created. He answers that God knows the forms or ideas or essences of all things—their whatness—in something like the way we do, since we know them by the forms that are in our minds. In our case those forms are obtained by intuiting or abstracting them from the material supplied by our senses (albeit with the help of an inner light or “vertical memory” that enables us to recognize them for what they are—Aquinas speaks of intellectus as the higher part of reason, and the closest we attain to the intuitive knowledge of the angels).[[6]] God, on the other hand, does not have senses. He does not even have ideas in the way we do. In God all things are one, and that means that all his ideas are one. In a sense he has ideas of everything, but all of them are identical with his own act of being. They are simply the various ways in which his own being can be participated. He knows things because he sees himself in them. He sees them as aspects or representations of his own isness.

Aquinas puts it like this. “Now, the divine intellect understands by no species [that is, no type of thing, or form] other than the divine essence.... Nevertheless, the divine essence is the likeness of all things. Thereby it follows that the conception of the divine intellect as understanding itself, which is its Word, is the likeness not only of God Himself understood, but also of all those things of which the divine essence is the likeness. In this way, therefore, through one intelligible species, which is the divine essence, and through one understood intention, which is the divine Word, God can understand many things.”[[7]] In fact, in this way God understands everything.

You may notice that with the mention of the Word we have begun to introduce the notion of the Trinity, but I won’t pursue that here. The main point is that Aquinas and Ibn ‘Arabi both agree that God knows all things through one act of knowing, which is identical with his act of being, the divine essence. God knows things by knowing the many possible reflections of his essence and their relationships to each other. These are what Ibn ‘Arabi calls the “immutable essences” (a’yan al-thabita).

Created Being

As for the actual existence of things, rather than God’s knowledge of them, Aquinas speaks of being in two senses—subsistent and non- subsistent. Divine Being is subsistent, or self-subsistent. Created being (esse creatum) or “the being common to all things” as Aquinas says, is non-subsistent, which means that it is dependent upon God. It is not a thing; it is that through which He makes things actual. It is the unity of all things that are and can be, the unity to which they belong, but which is in turn dependent upon God. Obviously, if it were identical to God then we would have a genuine case of pantheism, since everything would be part of God.

But it has to be admitted that this distinction is difficult to get one’s mind around.[[8]] Let’s see if Ibn ‘Arabi can help. Here I turn to Toshihiko Izutsu’s Sufism and Taoism, the first half of which is an exposition of Ibn ‘Arabi. As Izutsu points out—and as is indeed obvious from the most cursory reading of Ibn ‘Arabi in translation—for the Shaykh the Absolute per se is unknowable except through the various degrees of self-manifestation, corresponding to the five planes of being (Essence, Attributes, Actions, Images, and Senses). The best way to know the Absolute is to know ourselves, in accordance with the divine saying, “He who knows himself knows his Lord.” By knowing ourselves we know these various levels of manifestation, both outward and inward. We know, of course, that we are not self-subsistent but dependent on the Absolute that transcends us. In this way we discover the existence of God. But we are not left with an impossible, infinite gulf between God and the world. We discover an intermediate reality—that of the Attributes or Names of God.

These archetypes, according to Izutsu’s reading, are (as we have seen) the “unlimited number of relations in which the Absolute stands to the world. These relations, as long as they stay in the Absolute itself, remain in potentia; they are not in actu. Only when they are realized as concrete forms in us, creatures, do they become ‘actual.’”[[9]] There must therefore be a second plane of being, in which the multiplicity of the world is founded. This is the plane of the realized or manifest archetypes, which al-Qāshānī describes as the self-manifestation of the Necessary Being “in the One Substance” or the “One Entity.”[[10]] It seems to be the same as what Aquinas calls the ens commune or esse creatum, viewed as the totality of finite being gathered in a vast com- munity of mutual implication and exchange. The archetypes can be understood as naming God, and in that sense they are one, because they are aspects of the One, reflecting the archetypes in God’s mind. But they can also be understood as distinct from and related to one another, in which case they are multiple.

This implies a very important, indeed essential, role for man. We have said that the archetypes are multiple in creation, while as ens commune they form “one entity.” It seems to me that it must be man, or Adam, or Christ, who is this entity. The ancients indeed refer to our intellectual capacity to “become all things” (anima est quodammodo omnia).[[11]] The unity of created being is attained in the “I,” the becoming self-conscious of the (created) act of being, which is the heart of the Perfect or Cosmic Man. Man is situated at the center of all things, as the synthesis of all the Attributes, the Vice-Regent, the one who knows the Names of God manifested in creation—the creaturely image of God knowing Himself.

I reach the ens commune by meeting God halfway, as it were: I turn away from myself as object in order to discover myself as subject, as mirror. In doing so I forget myself, I strip away all that I knew of myself, in order to discover myself at the center of the world, indeed of every world. This experience of unveiling (kashf) is described by Izutsu as follows. “To the eye of a man who has attained this spiritual stage there arises a scene of extraordinary beauty. He sees all the existent things as they appear in the mirror of the Absolute and as they appear one in the other. All these things interflow and interpenetrate in such a way that they become transparent to one another while keeping at the same time each its own individuality.”[[12]]

For Christians, the centrality of Man in creation is implied in the Book of Genesis, and in the episode of the Naming of the Animals (Genesis 2:19-20; cf. Qur’an 2:13) we see that in the beginning Adam was the meeting point and master of the archetypes. St Thomas writes in the Summa: “Man in a certain sense contains all things; and so according as he is master of what is within himself, in the same way he can have mastership over other things.”[[13]]

Ibn ‘Arabi believed his account of the creation in the chapter on Adam in the Fusus to have been inspired by God. Let’s look at the first few paragraphs and try to interpret them. They tell us that God wished to see Himself in a “mirror” by projecting his Spirit into the Form of Man, Adam. In this way the immutable essences of His Names became manifest to Adam as to the “pupil of the eye” of the entire universe. This creation story is therefore framed in terms of consciousness, or perception. The I AM is reflected in its image, the “I am” of the Perfect Man, of which we in turn are like so many fragments. The world comes into existence through the relationship between the seer and the seen, the pupil (the “I” that sees) and the essences that reflect aspects of God to the seer.

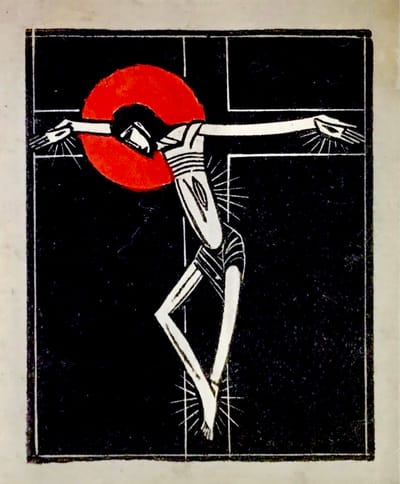

In the Hebrew and Christian Bible, in the Book of Genesis, the Spirit is similarly projected or breathed forth into a receptive mirror—the “deep” (Genesis 1:1-2)—and the divine word is spoken: in this tradi- tion not Kun! (Be!) but Let there be light! (Genesis 1:3). The words of the Zohar give us the connection: “This is the light that the Blessed Holy One created at first. It is the light of the eye. It is the light that the Blessed Holy One showed the first Adam; with it he saw from one end of the world to the other.”[[14]]

In the beginning we glimpse the end, both in the sense of “purpose” and in the sense of “destiny.” Each of us can achieve fulfillment only in that light, the radiance of being. We live most of the time in partial darkness, seeking ourselves and God among the objects and concepts our mind constructs and observes. But if once we are able to purify ourselves of all that, turn away from all objects and discover the subject, the “I” within, then we find the source of light.[[15]]

The quotation I began with was too short. The passage from St Maximus continues, and will serve as a fitting conclusion. It reads:

“Now the world is totally transfigured into God; its totality rests within the inner realm of God’s totality, its unity encounters the primordial unity. The radiance of God’s glory streams over it, as the splendor of the sun overpowers the light of the stars. Beings that exist as parts entrust themselves to the dominance of the whole. Every will that wills for itself is now annulled, since the creature no longer desires to belong to itself. There is only one activity left now, the activity of God—and that is precisely the highest level of freedom. The image of the burning bush will then be completely realized: ‘That ineffable, overwhelming fire, which burns away, hidden in the essence of things as in the bush’, will then burst out: not to consume the world, for it needs no fuel to burn. It will be a flame of love at the heart of things, and that flame is God himself.”

[[1]]: Hans Urs von Balthasar, Cosmic Liturgy: The Universe According to Maximus the Confessor (Ignatius Press, 2003), p. 353

[[2]]: Hans Urs von Balthasar, Cosmic Liturgy: The Universe According to Maximus the Confessor (Ignatius Press, 2003), p. 353

[[3]]: http://www.ibnarabisociety.org/articles/unityofbeing.html

[[4]]: There is no space here to explore the thought of John Duns Scotus, of whom it is often said that the being of God is indeed of the same kind as that of creatures, but raised to an infinite degree. In fact, Scotus says only that the concept of being is univocal. This univocal concept reduces ens to a kind of lowest common conceptual denominator, i.e., a lack of self‐contradiction.This, however, indirectly reflects the infinite self‐affirmation of the I AM (which for Scotus is Trinitarian), without anticipating the substantial content of that act in its infinite self‐determination

[[5]]: They are following Al‐Farabi and Avicenna (Ibn Sina), who introduced the distinction between wujud and mahiyya (whatness, quiddity, essence) into both Arabic philosophy and Latin scholasticism.There is no space here (nor am I qualified) to unravel the complex history of this discussion

[[6]]: Aquinas, Truth (Hackett, 1994), Vol. 2, Question 15, Art. 1

[[7]]: Summa Contra Gentiles (University of Notre Dame Press, 1975), Book 1, Ch. 53, [5]

[[8]]: See Aquinas, The Power of God (Oxford University Press, 2012), Question 7,Article 2

[[9]]: Toshihiko Izutsu, Sufism and Taoism:A Comparative Study of Key Philosophical Concepts (University of California Press, 1983), p. 41

[[10]]: Izutsu, Sufism and Taoism, p. 42

[[11]]: Josef Pieper is very clear on this point in his book Leisure the Basis of Culture (St Augustine’s Press, 1998), p. 82.“To have a world means to be in the midst of, and to be the bearer of, a field of relations.The second point is, the higher the level of the in‐ wardness or, that is to say, the more comprehensive and penetrative the ability to enter into relations, so the wider and deeper are the dimensions of the field of relations that belongs to that being; to put it differently: the higher a being stands in the hierarchy of reality, the wider and more profound is the standing of its world.” Indeed the Western philosophical tradition has“understood and even defined spiritual knowing as the power to place oneself into relation with the sum‐total of existing things” (p. 85)

[[12]]: Izutsu, Sufism and Taoism, p. 44

[[13]]: Summa Theologiae, Part One, Question 96, Article 2

[[14]]: Daniel Chanan Matt (trans.), Zohar: The Book of Enlightenment (Paulist Press, 1983), p. 51

[[15]]: In Aquinas’s account of the Beatific Vision, as in Ibn ‘Arabi’s teaching, God’s own essence cannot be known except by itself. If and when we achieve it—and this is normally only after death—this can only be because by divine grace we have come to know God by God, so that we are the“site” of God knowing Himself. “Those who see the divine essence see what they see in God not by any likeness, but by the divine essence itself united to their intellect.”This is from an account of the Beatific Vision in the Summa Theologiae of St Thomas, Part 1, Question 12, Article 9. The divine essence is united to our intellect by whatAquinas calls“the light of glory.” InArticle 5, St Thomas explains: “And this is the light spoken of in the Apocalypse (Revelation 21:23): ‘The glory of God hath enlightened it’—viz. the society of the blessed who see God. By this light the blessed are made ‘deiform’—i.e. like to God, according to the saying: ‘When He shall appear we shall be like to Him, and [Vulgate: ‘because’] we shall see Him as He is’ (1 John 2:2).” Possibly one might think of this “glory” as a clothing of light endowing us with vision—analogous to the clothing of grace Adam possessed in Eden before the Fall, a covering that was replaced by “garments of skins” (i.e. mere human flesh) at Genesis 3:21