Menu:

This article appeared in Sacred Web 8. To order this issue of Sacred Web and other back issues, click here.

Online Articles

Shadows and Strife:

Reflections on the Confrontation of Islam and the West

by Rodney Blackhirst and Kenneth Oldmeadow

Introduction

If there was any question that relations between Islam and the West are central to the times in which we live the question was emphatically removed by the events of September 11. Such traumatic events make us suddenly and acutely aware again of the whole history of Islamic/West tension and of the fact that this history is on-going and shapes not only our politics and religion but the very zeitgeist of the early 21st century. There are several conflicts in the world today that, in the broader scheme of things, must be regarded as world-historical in their import, and the Islamic religion features in most of them. Most notable, of course, is the conflict between the state of Israel and the dispossessed people of Palestine in the Holy Land. The return of the Jews to their ancient homeland is in itself a momentous event in the greater cycles of time, but the fact that this return involves a terrible clash with the Islamic world is an unavoidable feature of the same cycles. Similarly, the creation of a Muslim homeland, Pakistan, in the Indian sub-continent necessarily entails a perilous clash with a Hindu state, India, as the world’s youngest religion confronts the world’s oldest in a formal confrontation of nation-states. Conflicts in Africa, Central Asia, the Philippines and even the social tensions created by the settlement of Muslim communities in places such as Britain, France and Germany, should also be seen as symptomatic of the same phenomenon.

Since the September 11 attacks on New York and Washington there has been a veritable deluge of “news”, “opinion”, “commentary”, “analysis” and the like in the Western media, much of it issuing from politicians old and new, recycled CIA agents, defense personnel, so-called terrorism experts, Cold War veterans and media personalities. Much of the material with which the newspapers, television and radio have been awash might better be described as propaganda (the continuation of politics by other means, one might say). The following observations and reflections are not offered as a sustained analysis of the attacks and their aftermath, nor as a comprehensive review of Middle Eastern affairs: they should be read rather as a series of provocations to further analysis and thought. Our aim is to turn attention towards a wider context in which recent events might be situated and thus be better understood.

The September 11 Attacks, Terrorism and American Foreign Policy

Despite the headlines the attacks on New York and Washington were clearly not the product of “mindless terrorism”, “senseless violence” and “pure evil”; nor is it generally helpful to think in terms of “sick minds” and the like. The attacks were motivated, considered, deliberate. The fact that they are morally repugnant and that they have the most horrific human consequences does not make them unintelligible. The attacks on New York and Washington will indeed seem “senseless” unless they are historically located. One of the apparent but perhaps unconscious motives of the media coverage (with a few exceptions) would seem to be to discourage us from thinking about this context, and from asking some discomforting questions of our political leaders—both in America and elsewhere in the Western world. Similarly with White House/Pentagon rhetoric: despite President Bush’s repeated assertions, these attacks are not on “democracy”, “freedom”, “the American way of life”, the “Free World”; they are an extreme and grotesque response to America’s perceived role in the Middle East and elsewhere. To catalogue popular grievances with America in the Middle East would be a lengthy undertaking indeed, so let us simply note a few of the more conspicuous in passing: most significantly, America’s blinkered view of and highly partisan role in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; the politically ineffective but humanly disastrous sanctions against Iraq; America’s alliance with a raft of corrupt and “modernized” regimes throughout the Arabic world, especially Saudi Arabia; a jaundiced and highly selective American concern for human rights. No question, these attacks cannot be understood without reference to deeply entrenched historical injustices in which, to say the least of it, America has colluded. More generally it should be noted that the processes of “modernization (that is to say, changes such as secularization, industrialization, urbanization, and the “liberalization” of moral codes) and of globalization (corporatism, free trade, McDonalds in every town and village on the planet—in short, Business as Usual) are closely (and properly) identified with America. While abhorring the attacks, anti-globalists everywhere will recognize the World Trade Center and the Pentagon as highly specific targets relevant to their cause. (In later times might the World Trade Towers come to carry for our world the same kind of disturbing symbolism that the Titanic did for the complacent, hypocritical and hubris-ridden great imperial power of that day?)

Anyone with a dispassionate understanding of international Realpolitik over the last fifty-odd years cannot be unaware of the fact that the American state (as distinct from the American people at large) has repeatedly been guilty of the most cynical acts of subversion and terrorism—the assassination of democratically elected leaders; the covert sabotaging of properly constituted governments; the support of neo-fascist dictators, military juntas and murderous regimes; the invasion of other countries and repeated abuses of their sovereignty; the violation of the Geneva convention and many UN treaties and protocols; the deliberate killing of thousands of innocent civilians... the list goes on. Chile, Nicaragua, Guatemala, El Salvador, Grenada, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Panama, to name a few signal cases close to home.

The few voices in the media dissenting, in varying degree, from the prevailing “consensus” about the attacks and the appropriate American response—one might mention Noam Chomsky, Arundhati Roy, Robert Fisk, John Pilger, Karen Armstrong and Edward Said—have had little apparent effect on majority opinion which cleaves to a facile “Us and Them” mentality which is blind to the many infamies of American foreign policy in both its overt and covert aspects, and is susceptible to rhetorical sloganeering and posturing. Such a mentality is reinforced by President Bush’s simplistic assertion that all countries must align themselves with the USA or with the terrorists. As to the attacks themselves, there are those who say “Yes, but this is different: look at the scale of what has happened in New York”: one might reply, “What of the scale of the Nixon-Kissinger carpet-bombings of Laos and Cambodia, countries with which America was not at war?” or “What of America’s support of Saddam Hussein at the very time that he was gassing thousands of Kurds?” These are but two episodes in the annals of atrocities which America has either perpetrated or condoned. (In the end these “moral equivalence” arguments are probably futile but these sorts of comparisons may serve to highlight the one-eyed view often taken in the Western media, and by Western governments, of state-sponsored violence and human suffering.)

It might also be pointed out, in passing, that Great Powers almost invariably behave in this way. Nonetheless, given the official American rhetoric since World War II (the defence of “freedom” and “democracy”, the leadership of the “Free World”, the championing of human rights etc) the abysm between its avowed purposes and its actual foreign policy practice as an imperial power, is hypocritical in the extreme and thus all the more reprehensible. Again, it goes without saying that this in no way denies the equally palpable fact that the opponents of America have also often acted in the most brutal and unconscionable ways. Nor, of course, are these sorts of political crimes the exclusive preserve of Great Powers and terrorists, as history repeatedly testifies. Terrorism, and other acts of political brutality and barbarism, should be condemned and repudiated, no matter where they happen or by whom they are perpetrated—the American military and intelligence establishments as much as Stalinist apparatchiks, neo-fascist regimes, African dictators, religious and racist bigots, Maoist “reformers” and Western governments, as well as “Islamic” terrorists.

None of the above is to deny the basic decency of ordinary American citizens, and only the most heartless will fail to have been moved by the many examples of heroism and self-sacrifice we have seen on the part of many New York police, firemen, rescue workers and others in the aftermath of the September attacks. Nor is it to fall into the error, much encouraged by demagogues and rabble-rousers everywhere, of identifying a whole nation of people with the evils perpetrated by their government. We have heartfelt sympathy for the victims of terrorism everywhere, including the people of New York and Washington—one can hardly imagine the depths of trauma, grief and suffering which will come in the wake of these appalling attacks. At the same time we are mindful of the continuing sufferings of countless people in the Middle East, often as a direct result of American policy, and of the many deaths which will inevitably result from the American military campaign, not least amongst the vast numbers of Afghani refugees.

American “Fundamentalism”

In the public discussion of the attacks and their aftermath there has been a great deal of loose talk about “Islamic fundamentalism” (doubtless a highly significant factor but only very sketchily understood) but little reference to “American fundamentalism”—a political and psychological phenomenon, but not without religious underpinnings. What we have in mind here is the hegemonic national ideology whose most conspicuous ingredients include: a more or less unquestioning belief in the “American way of life” as self-evidently superior to all others, associated with a parochial, self-righteous and quasi-religious national ethos deriving particularly from white America’s historical origins and from Protestant forms of religious exclusivism; a political and imperial triumphalism which wants to ignore the lessons of history (Vietnam, Afghanistan, the Iranian hostage crisis and the like); a highly sentimental form of patriotism, easily fanned into militaristic adventurism. Insofar as the latter might be played out in concrete military and “surgical” operations, the chances of “success” would, to say the least of it, not seem promising. What is absolutely certain is that such “operations”, “successful” or not, will only exacerbate the tensions and hostilities referred to above. The only inevitable, long-lasting effect will be to incite millions of people in the Middle East and in other parts of the world to resent America (and its uncritical allies) even more. It hardly needs pointing out that any military campaign will also, inevitably, entail the killing of innocent civilians, and that many deaths amongst the huge numbers of Afghani refugees can be expected. We would do well to ponder Mahatma Gandhi’s question: “What difference does it make to the dead and the orphans and the homeless whether the mad destruction is wrought under the name of totalitarianism or the holy name of liberty or democracy… Liberty and democracy become unholy when their hands are dyed red with innocent blood.”

Not coincidentally, the aftermath of the September attacks brought into new focus many of the reasons why the USA is perceived as the enemy of religion and tradition. For several weeks the world was exposed to a heavy-handed “grieve-or-else” posture supported by an unprecedented outpouring of American patriotism and the peculiarly jingoistic excesses that characterize it. That this saturation of American sentimentality was well-nigh inescapable anywhere on the planet served to underline just how pervasive is the reach of American media culture; there are school children throughout the world who know more verses of ‘God Bless America’ than their own national anthem. Indeed, people felt the attacks acutely because, wherever there is television and cinema, many will know the famous streets of Manhattan better than they do the streets of their own big cities. No one calculates what manner of evil conspires to flood the world with this “information”, starving it of the Wisdom and Truth that is the primordial birthright of all people.

American jingoism also appears, to those not under its direct sway, as a form of enthusiastic quasi-religious fundamentalism with its roots in American Protestantism. President Bush invoked a key Biblical text of the American Protestant tradition, “He who is not for me is against me...” (implicitly and impiously transposing the authority of Christ’s words to the USA itself) and appealing to deep Christian impulses in the face of the “Muslim” attack. Extraordinarily, Bush even resorted to the use of the word “crusade” to describe the American response, a resurfacing of old rhetorical patterns that most liberals thought had long ago disappeared from discourse in “civilized nations”. This was reinforced with much reckless talk about “evil” and stark outlines of the battle of “good” against it — the very calling-card of any simplistic, fundamentalist view of the world and our times. The aftermath of the attacks showed up all manner of instances, great and small, of modernity/tradition problems with the US blithely filling its role as agent of the modern.

When the Western media describe the position of Osama Bin Laden as a “guest” in Afghanistan, for instance, they question the legitimacy of this guest relationship and invariably print the word “guest” in quotation marks. In fact, in this case, it seems, Osama Bin Laden has a formal guest relationship with his Afghan hosts. Modernity, knowing only the casual and superficial relations of atomized individuals, cannot appreciate why it is no easy matter to turn over a guest; a guest, in traditional cultures and cultures still illuminated by traditional values, is no mere casual acquaintance; the guest relationship is profoundly important. It becomes obvious that the West no longer knows what a guest is. In another report, suspected hijacker Muhammad Atta’s will is supposed to have contained the instruction: “Do not allow women at my funeral. I do not approve of it.” Modern-minded readers, unfamiliar with traditional patterns of grieving, will denounce this “sexism”, not recognizing the statement as an injunction against professional women mourners (wailers). These and other small differences and misunderstandings are underlined especially by the ill-chosen name for the “war on terrorism”, “Infinite Justice”, which had to be withdrawn after the US authorities were informed that “Infinite Justice” is, to Muslims, the preserve of Allah alone. It is salient that those in command of US power had no qualms about using the title to describe their cause and apparently never even guessed such a title might have religious implications. It is not just self-righteous to think one is yielding “Infinite Justice”, nor is it just an insensitivity to some peculiar Muslim theology; it shows a total insensitivity to the religious per se, and hence an utter failure by the Americans to appreciate the nature of the mentality that is opposed to them, and why. It is hard to imagine a worse faux paux in the circumstances. For the Americans to answer the September 11 attacks with a claim of “Infinite Justice” would serve to confirm in a stark way the claims of all those who have declared war on them for their alleged godlessness or because they are the “Great Satan”, embodiment of hubris.

Whatever immediate causes and motivations lay behind the September 11 attacks, from a traditional perspective the events must be situated in this broader framework. In political terms the significance of the events can be exaggerated. They merely represent the passage of strife to continental USA, but that strife has been manifest elsewhere for a long time; it is not something new. What is new is that Americans are suffering, and the world’s media is flooded with America’s shock at this change in their fortunes. However, on the ground, throughout the world—outside of the media matrix—few people were surprised and many, conspicuously those in Islamic countries, were pleased. “Bullseye!” said a taxi driver to a reporter in Cairo. On September 11 we saw a considerable escalation of the strife of our times, but that our times are strife-torn, and that Islam features in this strife, is no shock in itself. Few will admit it but anti-globalists everywhere feel some measure of ambivalence about the attacks. Similarly, religious people of whatever faith are empathetic to the human tragedy of September 11, but at the same time human nature loves to see the proud humbled.

Islam and the West

Islam claims to be both the last and the first of the world’s great spiritual orders and while its very name means “peace” there is no question that it plays a providential role in challenging the modern world to confront primordial spiritual realities and so is, as its critics never tire of saying, inherently warlike. In a well-known—we could almost say infamous—Hadith, the Holy Prophet said that, from the time of the advent of historical Islam, to the end of days, there would be no peace in the world. The peace of Islam is the “peace that surpasseth understanding”, not a secular or sentimental peace. Islam is in the world to remind us that our destiny will not be fulfilled in a false peace, and that there will be strife in the world for as long as men cleave to counterfeit absolutes. We can never be satisfied with a false peace, any more than false worship can ever satisfy our souls. Islam is a militant and uncompromising spirituality that insists upon this. More than other spiritual orders it addresses the problem of warfare. It finds warfare a constant in the human condition and wisely attempts to regulate it, direct it to noble ends and, finally, internalize it, making it an agent of self-transformation according to the well-known distinction between the lesser or outer Holy War (jihad) and the greater or inner Holy War, the war against the most pernicious of all counterfeit absolutes, the self.

In our times this inherent militancy of Islam has been sharpened against the West and against the whole project of modernity that is associated with it. Most recently, with the collapse of communism, the West has promoted a vision of a global order united by capitalist economics, American culture and liberal, secular values, a vision of the people of the world united around a McDonald’s hamburger, a Coca Cola peace. This utterly horizontal vision of the world threatens traditional ways of life everywhere, and it is not surprising that it encounters resistance, but the stiffest resistance comes from Islam which insists that such a world is not the telos to which the whole history of the human race has been inevitably progressing and which insists furthermore that a more noble destiny awaits man if he has the courage to be true to himself. Islam’s leadership in the struggle against the New World Order and its horizontal vision of our future is part of its providential role in this current cycle of time.

The roots of the American ideology—an ideology that seems so incapable of understanding Islam, especially as a pan-national force in today’s world—in Protestantism, and the whole Protestant background of America, is especially fascinating in the present context because Protestantism, in its deepest impulses, is historically the Christian response to the challenge of Islam. The central fact of the remarkably discontinuous tradition of Christian civilization is that the rise of Islam was a shock from which the Christian tradition never fully recovered. The whole trajectory of the West, and especially its history of successive ruptures from the well-springs of Tradition, should be seen in these terms. These are the inner mechanisms of the current world-cycle. Events such as September 11 lay them bare. Frithjof Schuon mentions this relation of Protestantism to Islam in Understanding Islam, where he describes the Protestant “nostalgia” for the primordial Islamic perspective, but it is not a theme developed in his writings. It is appropriate to develop it here.

For a deeper understanding of recent events and events that no doubt lie ahead it is important to remember the common roots of Islam and Christianity and to think of Islamic and Western civilizations as two sides of the same thing with Islamic/West tensions (as the Algerian scholar Hichim Djait put it) as “a battle raging in a single system.” Within this single system Protestantism (especially in its Calvinist forms) is the ultimate Christian response to Islam or, to borrow ideas from scholars like Norman Cohn, it is like a “shadow”, the “tails” side of the coin. It is this that explains the remarkable similarities between Islam and Protestantism as religious typologies. Both, for instance, as the sociologists will tell us, are religious movements developing out of urban trading classes, from a grappling with a literacy revolution with an emphasis on The Book, a rejection of priesthoods and of celibacy, a repudiation of images, and so on. The parallels between Islam and Protestantism are numerous and remarkable but rarely explored. (Histories of the Reformation often overlook the importance of the threat of the Turks at the time. The Reformation was when Christendom finally broke out of the “Crusade” approach to tackling Islam and decided to reform itself into an urban trading outfit to match the infidels.)

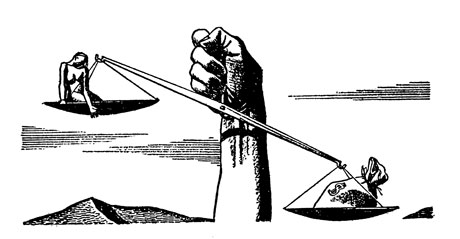

In the current climate it is not surprising that Samuel Huntington’s “Clash of Civilizations” scenario is making a comeback. However, to understand Islam/West relations one must appreciate that it is not a clash of polar opposites but of contending similars. A recent commentator asked: “But why has all the trouble of the crusades and the whole history of enmity between Islam and Christendom been heaped upon the USA?” It is a good question. There is more to it than just the fact that the USA is an historical extension of European civilization. It is the nature of American Protestantism and its influence upon American ideology that really clashes with Islam, and they clash because, at their deepest levels, they are contending similars.

To sustain this view, of course, we must, as with traditionalist thinking generally, regard Protestantism (Calvinism especially) as, in a sense, an aberration or a perversion of the Christian tradition, a pathology created by the irritant Islam (within the single system). To put it plainly, the threat of Islam twisted Christianity out of shape. Perhaps this was a movement of providence, potential in the tradition from the outset, but nevertheless it disturbed the equilibrium of Christian civilization which, beginning in the Middle Ages, but more obviously from the Renaissance onwards, began to lurch from crisis to crisis and revolution to revolution. The historical reality of Islam—no one denies Muhammad was an historical man—pushed Christian thinking towards an historicized understanding of Christianity (which, properly understood, is, as it was throughout the Middle Ages, more mythological than historical). Similarly, contact and rivalry with the Muslims, and especially the Sufis, in Spain, Sicily, the Crusade States and at other points introduced new patterns of piety into Christianity that disturbed profoundly the ancient patterns and that ultimately gathered into the enthusiasm of the Reformation. Protestants conceive of Jesus and his disciples in ways that would be much more fitting to Muhammad and his Companions. This is not true of traditional Christian piety—Catholic, Orthodox, Coptic—only of Protestantism, and Calvinism especially. More obviously, who can fail to notice the ways in which Protestants treat the Bible and how this reflects the way Muslims treat the Qur’an? In traditional Christianity, of course, the Bible is a step removed from God’s Word which is Christ Himself, the Incarnate Logos; it is merely a record of the witness of the Logos, not the Logos Itself. In Islam, the Qur’an (and not Muhammad) is the Incarnate Logos. In Protestantism, this function in the theology is given (perversely) to the text of the Bible itself. To exaggerate the point: Protestantism is a Christian imitation of Islam, a Christianity adapted to Islam. The identification of America as the Great Satan, and converse Western portrayals of various brooding, turban-clad villains as the personification of living evil, take us very deep into a schizoid “single system” that is defining world events and the trajectory of our times.

Islamic Fundamentalism in Perspective

Needless to say, those behind the attacks are themselves guilty of hubris in thinking that God is on their side. Islamic fundamentalism is itself a symptom of modernity and represents a profound disequilibrium within the bosom of modern Islam—this is an essential consideration in any traditionalist assessment of recent events. In many respects Muslim fundamentalism is the very inverse of the modern traditionalist “movement”, inasmuch as the latter has strong roots in Islam. Both, it must be said, are an expression of the modern urge to return to primitive roots, conscious that modernity has cheated man of his nobility, but whereas traditionalists seek a renewal of the spiritual kernel of the Islamic faith—and by extension all faiths (which converge at their esoteric centre), externalist fundamentalism constructs a fictitious primitive simplicity in the image of its own limitations, and the result is acute particularisms that manifest in practice as grotesque intolerance. The Taliban’s wanton destruction of Buddhist statues and the “marking” of Hindus “for their own protection” are just two examples from the months prior to September 11. The Wahabism that is apparently behind the recent attacks is, let us remember, intractably opposed to Sufism and all esoteric aspects of Islam, has expelled the Sufis from the Holy Prophet’s own land, closed the shrines of the saints, imposes terrible strictures upon the pilgrims to the Holy Places and, in fact, has drawn Islam in its spiritual heartland towards an empty externalism since the misnamed “Islamic Reformation” of the 18th century. The events of September 11 remind us once again that, in these troubled times, political reactionaries and literalists, not authentic spiritual masters, speak for Islam on the world stage. In this context it is understandably difficult for people in the West to appreciate that Islam has any inner dimension at all.

The term “fundamentalism” is itself somewhat problematic: who, after all, can object to a return to the fundamentals of the religious tradition? Nor should we make the mistake of conflating religious orthodoxy and “fundamentalism”. As the editor of this journal recently noted, the term “disguises a host of complexities” (Sacred Web 7). The Taliban and other such groupings should more precisely be seen as manifestations of Islamic externalism or literalism, a form of Islam which is lop-sided in its adherence to a rigid dogmatism and formalism, and, consequently, is generally hostile to the esoteric traditions of Islamic mysticism, evidenced by the antipathy of many of these groups to the Sufi orders.

Terrorism of the kind we have seen this week is clearly quite incompatible with the actual teachings of the Prophet and of the Islamic tradition. Both suicide and the taking of innocent lives are unequivocally prohibited by The Qur’an whilst jihad is in its fullest sense a spiritual ideal of self-conquest, and on the material and social plane can only constitute a defensive war to protect the faith and the faithful. There is no doubt that the vast majority of Muslims feel the same kind of moral revulsion over these attacks that the rest of the world does (though, as we have noted, this is often admixed with ambivalent feelings arising out of a detestation of America’s role in the contemporary world). There are extremists and bigots in every country, every culture: to judge the whole of Islam on the basis of this or that terrorist group would be akin to judging Christianity not on the basis of its teachings or its finest exemplars but by those fanatics and hate-mongers who betray its teachings while purporting to act in its name. History, alas, is replete with examples of such treachery and we need not look too far in the contemporary world to find it—in Ireland, the Middle East, the Balkans, the Indian sub-continent, Japan, America.

The terrorist attacks seem to have been used to license all manner of racists, bigots and cranks to ventilate their own poisonous forms of ignorance, hatred and prejudice in the media. Here in Australia the tabloids and commercial media, in particular, seem quite happy to accommodate such rantings while radio shock-jocks pour more fuel on the fires of hatred and intolerance. At this very tense time it is imperative that citizens in the Western world express our solidarity with and support for our fellow citizens who belong within the fold of Islam and/or who are of Middle Eastern background. No doubt, in the sort of climate created by these events, many Jewish folk will also be feeling apprehensive about the possible re-ignition of a virulent but temporarily latent anti-Semitism in many parts of the world. It is especially incumbent on Jews, Christians and Muslims of good will everywhere in the world to create bonds of fellowship and mutual respect. One way in which this can be done is by focusing, amongst other things, on the vast common ground shared by these great Occidental monotheisms, not least in the ethical domain.

Exotericism, Esoterism and the “Problem” of Religious Pluralism

At times like these we would do well to return to the teachings of the great spiritual figures and ask ourselves what light they might be able to shed on these events, on our responses, on our ways of understanding ourselves and our world. One thinks of the great foundational teachers—Moses, Jesus, Muhammad, Gautama Buddha, Lao Tzu, Guru Nanak to name a few—and of more recent leaders and thinkers who have confronted some of the deepest moral-political dilemmas of our time, such as Mahatma Gandhi, Simone Weil, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Thomas Merton, Nelson Mandela, Desmond Tutu and the Dalai Lama. (Why, it might be asked, have the Dalai Lama’s sober and thoughtful reflections received such scant media attention whilst at the same time people like Dr Kissinger are given apparently endless air-time and press space?) We should also remember the mysterious power and efficacy of prayer, meditation and ritual observance in these dark times: these practices can bring incalculable benefits in ways which we do not understand. Let us also not forget the redemptive power of the hermit, the monk, the recluse, the bodhisattva, the nun, the sannyasi who, in Thomas Merton’s words, “out of pity for the universe, out of loyalty to mankind, and without a spirit of bitterness or resentment, withdraw into the healing silence of the wilderness, or of poverty, or of obscurity, not in order to preach to others but to heal in themselves the wounds of the whole world.”

In the intellectual domain, what is needed, perhaps more than ever before, is a proper understanding of the metaphysical basis of the essential unity of all integral religions. For some time past it has been a commonplace that we are living in an unprecedented situation in which the different religious traditions are everywhere colliding. In the last few centuries European civilisation has itself been the agent for the disruption and extirpation of traditional cultures the world over. Since then all manner of changes have made for a “smaller” world, for “the global village”. Now we are confronted with apocalyptic scenarios envisaging “the clash of civilisations”, of new “holy wars” and “crusades”, of the violent confrontation of militant “fundamentalists” and the forces of “modernity”. In this context, the question of the relationship of the religions one to another and the imperatives of mutual understanding take on a new urgency for all those concerned with fostering a harmonious world community. In an age of rampant secularism and skepticism the need for some kind of inter-religious solidarity also makes itself ever more acutely felt.

As to the fate of the religious traditions, three obvious possibilities present themselves in the face of the processes of modernisation and globalisation, each disastrous for humankind’s spiritual welfare: intensifying internecine theological and/or political warfare; the disappearance of the religions under the onslaughts of modernity; the dilution of the religions into some sentimental, “universal” pseudo-religion. If these malignant possibilities are to be averted we need a proper understanding of what Frithjof Schuon has called “the transcendent unity of religions”. Crucial to any recognition of this unity is the ability to discern the distinction between the exoteric and esoteric dimensions of the great religious traditions, Christianity and Islam amongst them, and thus to forestall the terrible excesses of religious literalism. (This was the subject of an earlier article in Sacred Web 5). Recall this passage from Frithjof Schuon’s The Transcendent Unity of Religions (1975 ed, 9), one which takes on a new resonance in the present circumstances:

![]() The exoteric viewpoint is, in fact, doomed to end by negating itself once it is no longer vivified by the presence within it of the esoterism of which it is both the outward radiation and the veil. So it is that religion, according to the measure in which it denies metaphysical and initiatory realities and becomes crystallized in literalistic dogmatism, inevitably engenders unbelief; the atrophy that overtakes dogmas when they are deprived of their internal dimension recoils upon them from outside, in the form of heretical and atheistic negations.

The exoteric viewpoint is, in fact, doomed to end by negating itself once it is no longer vivified by the presence within it of the esoterism of which it is both the outward radiation and the veil. So it is that religion, according to the measure in which it denies metaphysical and initiatory realities and becomes crystallized in literalistic dogmatism, inevitably engenders unbelief; the atrophy that overtakes dogmas when they are deprived of their internal dimension recoils upon them from outside, in the form of heretical and atheistic negations.![]()

It is precisely these principles and insights which are so often overlooked by those groups and movements gathered together under the loose canopy of “fundamentalism”, wherever they be found.

At a time when the outward and readily exaggerated incompatibility of divergent religious forms is used to exploit all manner of anti-religious prejudices the exposure of the underlying unity of the religions is a task which can only be achieved through a trans-religious understanding. The open confrontation of different exotericisms, the vandalism visited on traditional civilisations everywhere, and the tyranny of secular and profane ideologies all play a part in determining the peculiar circumstances in which the most imperious needs of the age can only be answered by a recourse to traditional esotericisms. There is perhaps some small hope that in this climate and given a properly constituted metaphysical framework in which to affirm the “profound and eternal solidarity of all spiritual forms” the different religions might yet “present a singular front against the floodtide of materialism and pseudo-spiritualism” (Schuon, Gnosis: Divine Wisdom).

The “philosophical” question of the inter-relationship of the religions and the moral concern for greater mutual understanding are, in fact, all of a piece. We can distinguish but not separate questions about unity and harmony; too often both comparative religionists and those engaged in “dialogue” have failed to see that the achievement of the latter depends on a metaphysical resolution of the former question. A rediscovery of the immutable nature of man and a renewed understanding of the sophia perennis must be the governing purpose of the most serious comparative study of religion. It is, in Seyyed Hossein Nasr’s words, a “noble end... whose achievement the truly contemplative and intellectual elite are urgently summoned to by the very situation of man in the contemporary world” (in Philosophy East and West XXII, 1972, 61). These words, written three decades ago, are all the more compelling in the current climate. The sophia perennis, ultimately, can lead us to that “light that is neither of the East nor the West” (the Qur’an: 24,35). It is the light towards which we are beckoned by the great mystics of all traditions, the light that moved Rumi to say:

![]() I am neither Christian nor Jew nor Parsi nor Muslim. I am neither of the East nor of the West, neither of the land nor sea... I have put aside duality and have seen that the two worlds are one. I seek the One, I know the One, I see the One, I invoke the One. He is the First, he is the Last, he is the Outward, he is the Inward.

I am neither Christian nor Jew nor Parsi nor Muslim. I am neither of the East nor of the West, neither of the land nor sea... I have put aside duality and have seen that the two worlds are one. I seek the One, I know the One, I see the One, I invoke the One. He is the First, he is the Last, he is the Outward, he is the Inward.![]()